Impact on people, technology and infrastructure

NASA/JPL, DLR (editing)

A natural spectacle like the Northern Lights is among the more pleasant aspects of space weather. However, solar activity can also pose risks to people and, in particular, to today’s highly technological and mobile society. This has been demonstrated on numerous occasions in the past.

While the Carrington Event of 1859 only affected telegraph lines, a failure of today's modern power grids would have far more devastating consequences. One recent study estimated that the damage from a comparable event could amount to approximately one trillion US dollars in the United States alone. Such power outages could result in disruptions to supply chains for everyday goods and restrict human mobility, particularly due to the temporary disruption of air travel.

Extreme space weather events can also damage space infrastructure, particularly satellite-based communication and navigation systems. Space weather can also negatively impact humans in space, for example during future crewed missions to the Moon or Mars.

Disruption of communication and navigation

The ionosphere was largely discovered and studied by early radio pioneers, who found that the reflection of radio signals from the ionosphere can be both a useful tool for shortwave radio and a source of interference for medium- and longwave radio.

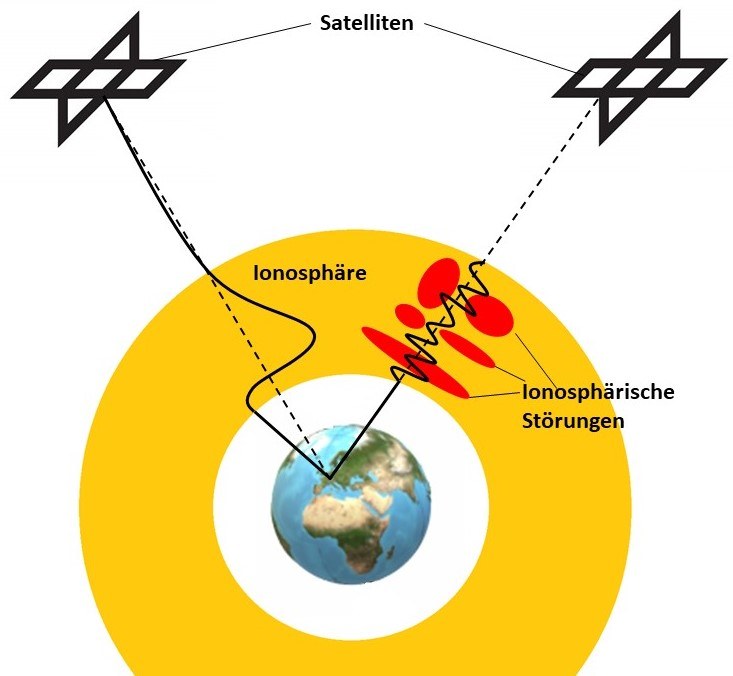

Today, ground-based communication is increasingly being replaced by satellite communication, which relies on frequencies that are not reflected by the ionosphere. Nevertheless, signals are still affected when passing through the ionosphere, even during normal solar activity, as radio signals are 'deflected' by the ionospheric plasma. The key factor in this process is the total electron content (TEC) of the ionosphere – the number of electrons along the signal path.

This is highly relevant for satellite-based navigation, where positioning is determined by the time difference between signals arriving from multiple satellites. The deflection of signals and the resulting minor time deviation lead to slight errors in positioning, known as a propagation error.

Such errors are particularly hazardous in applications that require highly precise positioning, such as driverless cars. TEC maps from ionospheric models allow these deviations to be recorded and corrected.

Space weather can also cause ionospheric disturbances – strong temporal and spatial fluctuations in the electron content. Such disturbances create a type of noise known as 'scintillation' in the satellite signal, which can lead to additional uncertainties or, in the worst case, complete signal loss.

Satellite reentry

Space weather can not only disrupt satellite-based communication and navigation but can also directly affect satellites themselves. During a geomagnetic storm, strong electrical currents generated in the ionosphere heat both the atmosphere and the ionosphere itself. As the upper layers of the atmosphere heat up, their gas density increases, and the atmosphere expands.

As a result, satellites in low Earth orbit (between 200 and 2000 kilometres above Earth's surface) are exposed to greater atmospheric drag, causing them to lose altitude more quickly than usual and increasing the risk that they burn up in the atmosphere. Correcting their orbits, however, requires significant amounts of propellant – a limited resource onboard a satellite. If there is no possibility to raise the satellite, a geomagnetic storm can significantly shorten its operational lifespan. Since 2020, the number of satellites in orbit has increased dramatically, particularly due to constellations of small satellites, further exacerbating the issue.

Sociedad de Astronomia de Caribe

A striking example of this was the 'Starlink Event': In early 2022, 49 satellites were launched into an intermediate orbit at an altitude of 300 kilometres, before they were to be boosted to their final orbit.

However, a moderate geomagnetic storm occurred at the same time. The increased atmospheric density along the satellite trajectories prevented 38 of the 49 satellites from reaching their final orbits, necessitating their controlled reentry and burn-up.

Why a relatively weak space weather event had such severe consequences remains the subject of ongoing research.

An oxygen spectrometer for atmospheric research (OSAS-B)

In low Earth orbit, atomic oxygen is the predominant cause of satellite weathering and deceleration. Depending on solar activity, the density of atomic oxygen can be subject to significant fluctuations.

To observe atomic oxygen in the mesosphere and lower thermosphere, the DLR Institute of Optical Sensor Systems in Berlin has developed the OSAS-B (Oxygen Spectrometer for Atmospheric Science from a Balloon) instrument. This device measures the radiation emitted by atomic oxygen due to thermal excitation. OSAS-B is the first instrument of its kind capable of measuring the thermally excited ground-state transition at 4.7 terahertz, providing insights into local temperature and density.

The first scientific deployment of OSAS-B took place in 2022 using a research balloon launched from Kiruna, Sweden. It is also part of DLR’s contribution to the Canadian STRATO campaign, in which balloon flights are launched into the stratosphere in a project organised by the French space agency CNES in cooperation with the Canadian Space Agency (CSA).

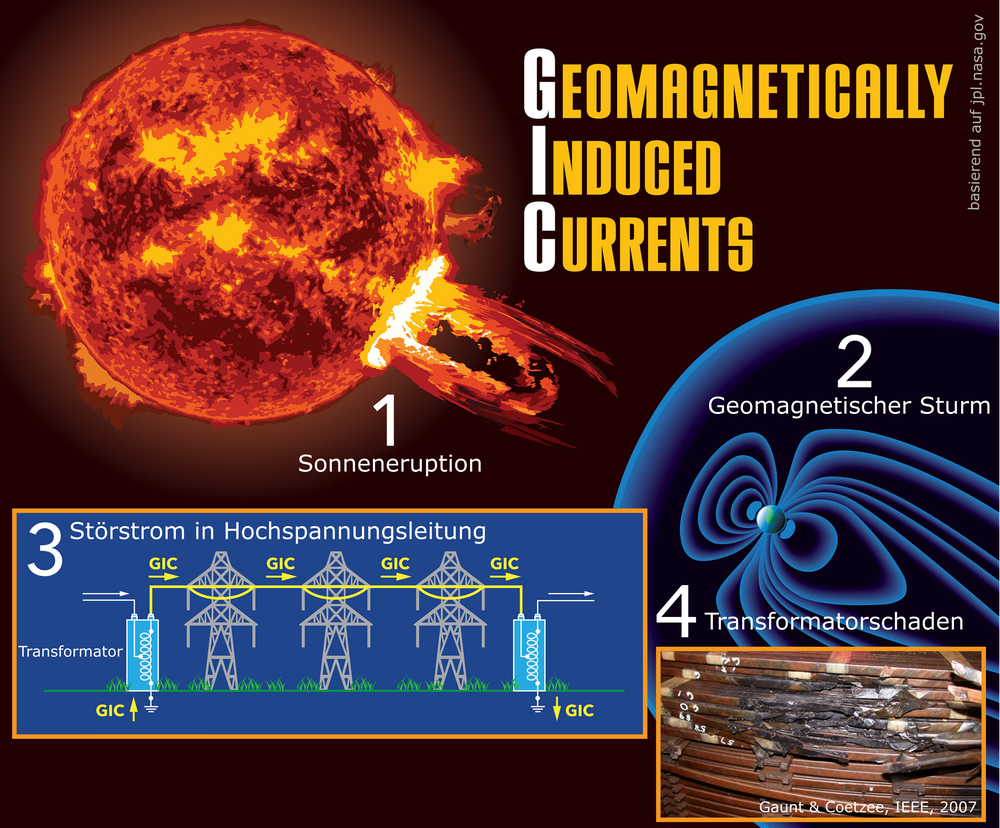

Power grids – faulty connections and voltage instability

Geomagnetic storms affect power grids through electromagnetic induction – the same principle that underpins everyday devices such as bicycle dynamos. A power line between grounded transformers allows current to flow through an electrical circuit that includes the electrically resistant ground.

A geomagnetic storm generates a voltage through fluctuations in the magnetic field over time. This voltage drives an unwanted geomagnetically induced current (GIC) – which places a direct current load on components of the 50-hertz alternating current grid, particularly on grounded transformers in the 380-kilovolt high-voltage transmission network.

The GIC introduces a direct current into transformer windings, which shifts the operating point of the magnetic circuit in the transformer core. This can lead to core saturation in one half of the alternating current cycle, causing a sudden surge in the excitation current, increased reactive power demand and the introduction of harmonic waves into the grid. This can lead to harmful effects, including the incorrect switching of protective devices, voltage instabilities and, in extreme cases, irreparable transformer damage or even widespread power outages.

Such phenomena are known as blackouts. Particularly well-known blackouts caused by geomagnetic storms occurred in March 1989 in Quebec, Canada, and in October 2003 in Malmö, Sweden. Damage to transformers in South Africa has also been linked to geomagnetic storms.

Repeated exposure to geomagnetically induced currents may also reduce the service life of grid components in the long term. As part of the RESITEK project, the DLR Institute of Solar-Terrestrial Physics is developing robust regional risk analyses to enhance power grid resilience in the event of a disaster.

The danger of radiation sickness

NASA

When the astronauts of NASA's Apollo 16 Moon mission returned safely to Earth on 27 April 1972, little did they know that they had escaped a major disaster. Just over three months later, a series of solar storms occurred that, according to recent research, could have been as strong as the Carrington Event of 1859. Fortunately, the orientation of the interplanetary magnetic field meant the geomagnetic storm was comparatively mild.

Had the Apollo astronauts been outside Earth's protective magnetic field at the time of the storm, they would have suffered severe health consequences. Even inside their spacecraft, shielded from most solar wind particles, the astronauts would have received a radiation dose equivalent to approximately 100 upper body X-rays. Outside the spacecraft – on the lunar surface, for example – they would likely have experienced acute radiation sickness, with potentially fatal consequences.

For future Moon and Mars missions, continuous monitoring and forecasting of solar activity will be essential. In an emergency, the crew will receive an early warning, allowing them to retreat to shielded areas within the spacecraft, the Moon or Mars base. A similar approach is already in place on the International Space Station ISS, where astronauts are instructed to avoid less protected areas during solar storms. Although the ISS is located within Earth's magnetic field, at an altitude of 400 kilometres, the atmosphere here is too thin to intercept incoming particles in the solar wind. While the crew is not in immediate danger, a certain degree of caution is still required.

Alongside NASA and other parties, the DLR Institute of Aerospace Medicine in Cologne is researching how solar radiation in space can be better detected, so that effective protection measures can be provided for future astronaut crews.