Earth and its magnetic field

NASA

Space weather refers to the effects of solar activity – particularly solar storms – throughout the heliosphere, the vast region of space influenced by the Sun, extending out far beyond Pluto. Within this region, charged particles and radiation from the Sun interact with planetary magnetospheres, ionospheres and atmospheres. At Earth, these 'solar-terrestrial coupling processes' are highly complex, making near-Earth space extremely chaotic – justifying the analogy to meteorological weather.

The magnetosphere

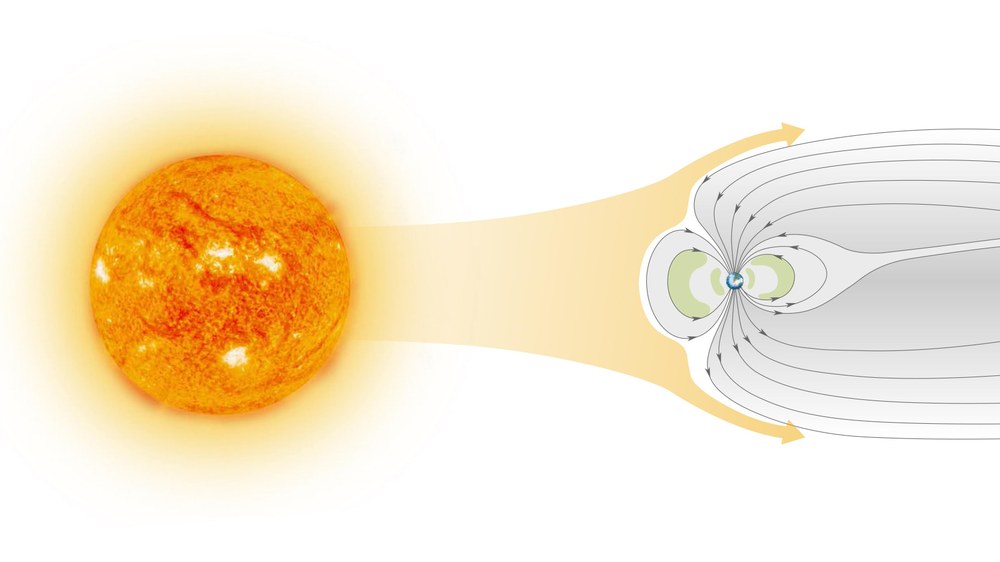

The magnetosphere generally describes the area around a celestial body in which the behaviour of charged particles is mainly determined by its magnetic field. As such, Earth's magnetosphere is the area of influence of its magnetic field, which is generated by the geodynamo – a process driven by the convective flow of molten iron in Earth's outer core, combined with Earth's rotation.

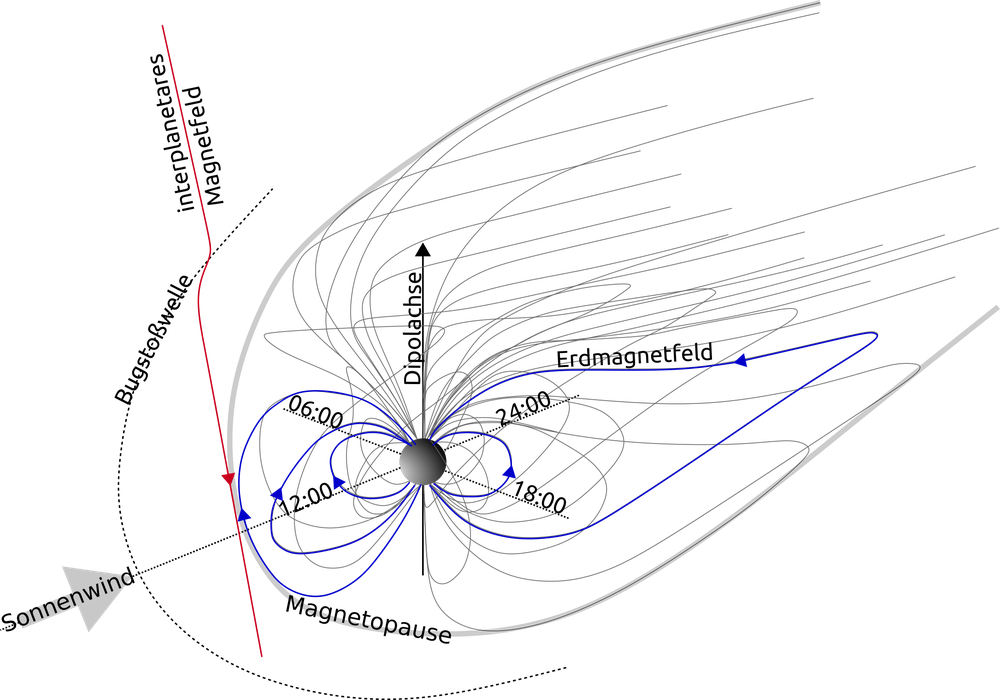

Earth's magnetic field corresponds approximately to a tilted magnetic dipole centred at the Earth's core. The magnetic field can be visualised as the field of a bar magnet with a north and south pole aligned along Earth's longitudinal, or rotational, axis. The magnetic field of such a magnet exerts its force along field lines, typically revealed by iron filings in school physics lessons. The strength of the field is proportional to the distance between these lines – where the field is stronger, the lines are closer together.

Earth's dipole field is currently tilted by approximately 9.2 degrees relative to its axis of rotation. This causes the deviation between geomagnetic and geographic poles. The strength of the field varies from around 60,000 nanoteslas at the poles to 30,000 nanoteslas at the equator. Compared to artificial electromagnets, which are in the range of a several teslas – many billion times higher – this is miniscule.

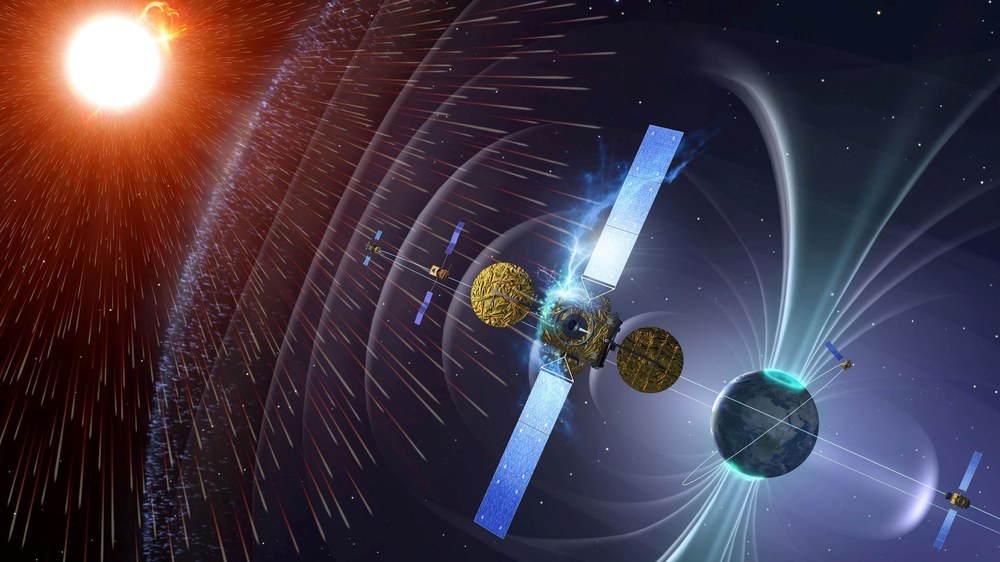

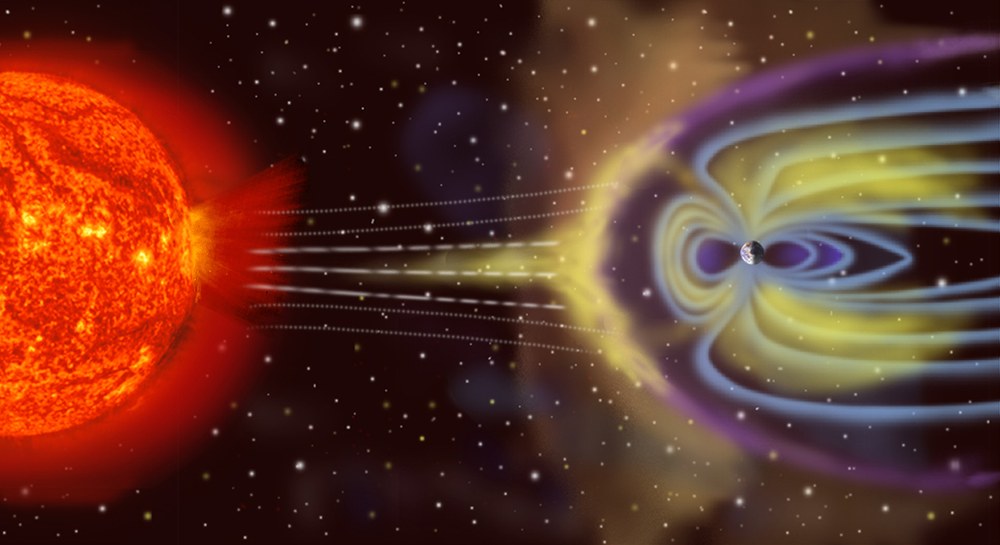

Despite its relatively low strength, Earth’s magnetic field plays a crucial role in shielding our planet by deflecting most of the solar wind. The magnetosphere can be seen as a kind of protective bubble in the Sun's particle stream that shields life and electronic equipment from harmful radiation. Due to the constant pressure from the solar wind, Earth's magnetic field is somewhat compressed on the dayside and stretched on the nightside. On average, the outer boundary of the magnetosphere on the dayside – the magnetopause – is about 63,000 kilometres from Earth's surface.

During solar storms (such as coronal mass ejections), the protective shield of the magnetosphere is weakened by the incoming plasma cloud. This weakening allows an above-average number of charged particles to penetrate the magnetosphere, which travel along the magnetic field lines into the polar atmosphere and create the auroras. At the same time, Earths magnetic field becomes particularly strong and is distorted in a distinctive way. Such disturbances are called geomagnetic storms and can last for several days.

The degree of coupling between the solar wind and the magnetosphere depends primarily on the relative orientation of the interplanetary magnetic field – the magnetic field transported by the solar wind – and Earth's magnetic field at the magnetopause. When these fields point in opposite directions, the impact of a coronal mass ejection increases, transferring more momentum and energy into the magnetosphere and intensifying geomagnetic storms. During extreme events, the field strength can fluctuate by more than 1000 nanoteslas – only a few percent of the average total field strength.

Background info – key figures |

|---|

Geomagnetic indices make it easier to classify the intensity of disturbances. The planetary index (Kp), is particularly important, which defines internationally recognised storm classes from 'minor' (Kp=5) to 'extreme' (Kp=9). |

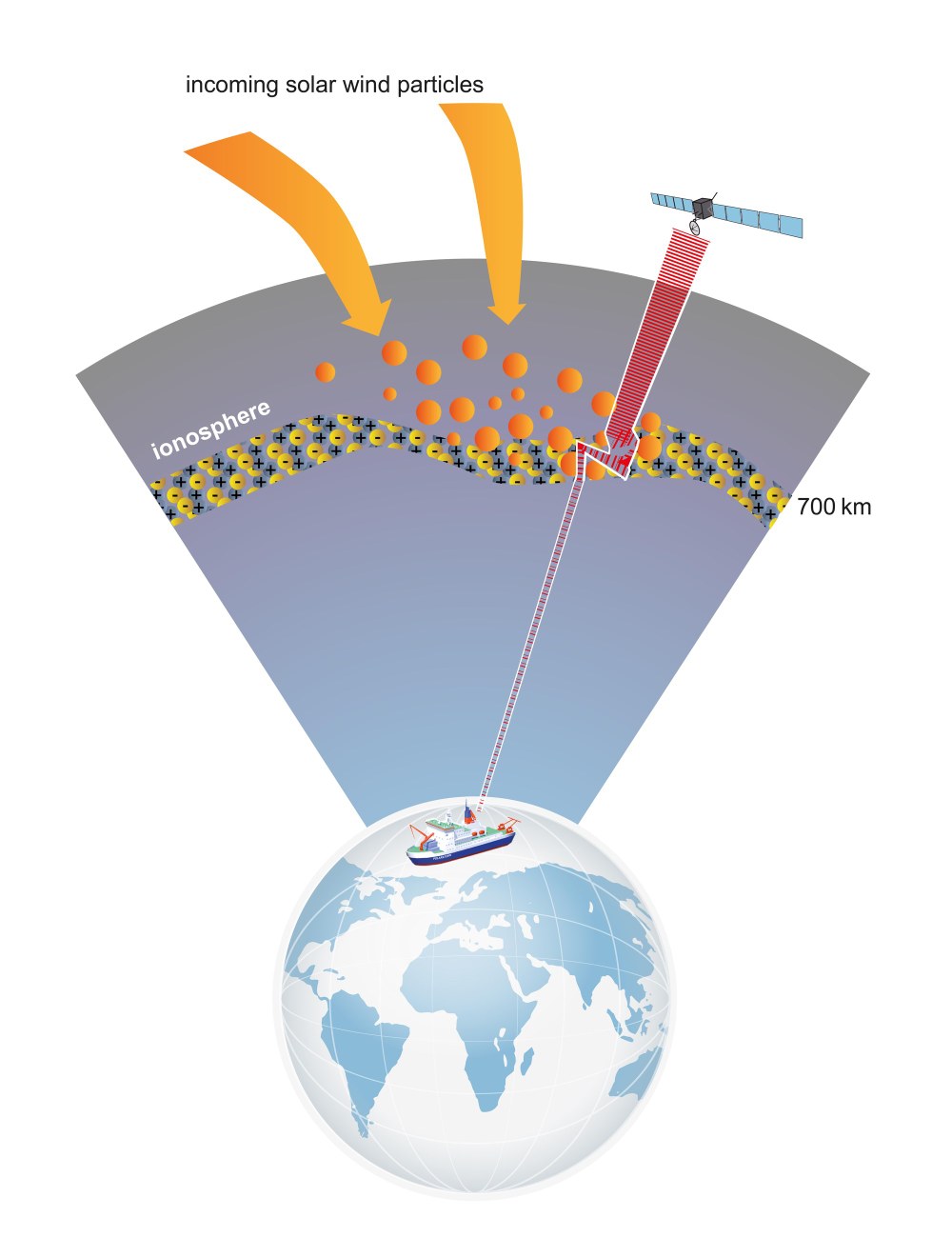

The ionosphere

The Sun's high-energy radiation is absorbed in Earth's upper atmosphere, providing enough energy to ionise a portion of the atmospheric gases – meaning individual electrons are stripped from gas particles. Above an altitude of approximately 70 kilometres, these charged particles form a plasma that gives the ionosphere its name.

The importance of the ionosphere was evident from its discovery: early attempts at radio communication in the late 19th century were limited to short distances. However, it was discovered that radio signals at certain frequencies could cover extremely long distances. This led to the hypothesis of an electrically conductive atmospheric layer (E layer) at an altitude of about 100 kilometres, which reflected certain radio waves.

Further research led to the discovery of additional layers, which were subsequently named in alphabetical order:

- D layer (ranging from approximately 70 to 90 kilometres in altitude)

- E layer (extending from roughly 90 to 150 kilometres)

- F layer (spanning approximately 150 to 1,000 kilometres)

These three layers together form Earth's ionosphere. They are created by complex interactions involving a wide variety of physical and chemical processes, so they are constantly changing.

Solar activity, particularly solar storms, also has a significant influence on the ionosphere. This is why many space weather processes occur in this region, posing challenges for radio communication. The strength and range of a radio signal depend on the current state of the ionosphere's layers. Only radio signals with a frequency above approximately 10 megahertz can penetrate the ionosphere, which why navigation satellites operate in this range. However, even these signals are 'deflected' by the ionosphere, particularly during geomagnetic storms, a factor that must be accounted for in satellite navigation systems.