The aurora – a spectacular display in polar skies

©ESA

The polar regions play a special role in the formation of the Northern Lights due to the shape of Earth's magnetic field. Solar wind particles are deflected along magnetic field lines that run parallel to Earth's surface. These particles only hit Earth's atmosphere at high latitudes, where the magnetic field lines curve steeply downward, almost perpendicularly, toward the planet’s surface. As a result, the atmosphere is excited by these incoming particles and enters metastable states, meaning atmospheric particles store the incoming energy temporarily and then release it again in the form of light. This afterglow phenomenon is known as the aurora and is the same principle that gives rise to fluorescent lettering, as used in watch dials.

Auroras occur in a variety of colours and shapes, depending on the type of incoming particles and the atmospheric particles they excite. Excited nitrogen molecules, for example, produce the rarer blue and violet/pink auroras. The most frequently observed aurorae are red and green, but a common misconception is that these two colours originate from different atmospheric gases – oxygen and nitrogen. In reality, both colours actually arise from the excitation of atomic oxygen, just in two different states.

The first oxygen state, in which red light is emitted upon de-excitation, is the most common. It has a relatively long lifetime of 110 seconds, meaning that red auroras can only occur above 200 kilometres where the atmosphere is thinner and particle collisions are less frequent. At lower altitudes, frequent particle collisions can suppress the red aurora by de-exciting oxygen atoms before they emit light.

ESA/Holzworth/Meng

Green auroras, however, are emitted when the second oxygen state is de-excited. This state has a much shorter lifetime of just 0.75 seconds and so occurs at lower altitudes than red auroras. Green auroras are observed in a very narrow range of approximately 100 to 120 kilometres in altitude. Here, a particularly large number of oxygen particles are excited. Due to their short lifespan and lower altitude range, green auroras are perceived as more intense than their red companions, reinforced by the fact that the human eye is more sensitive to green wavelengths.

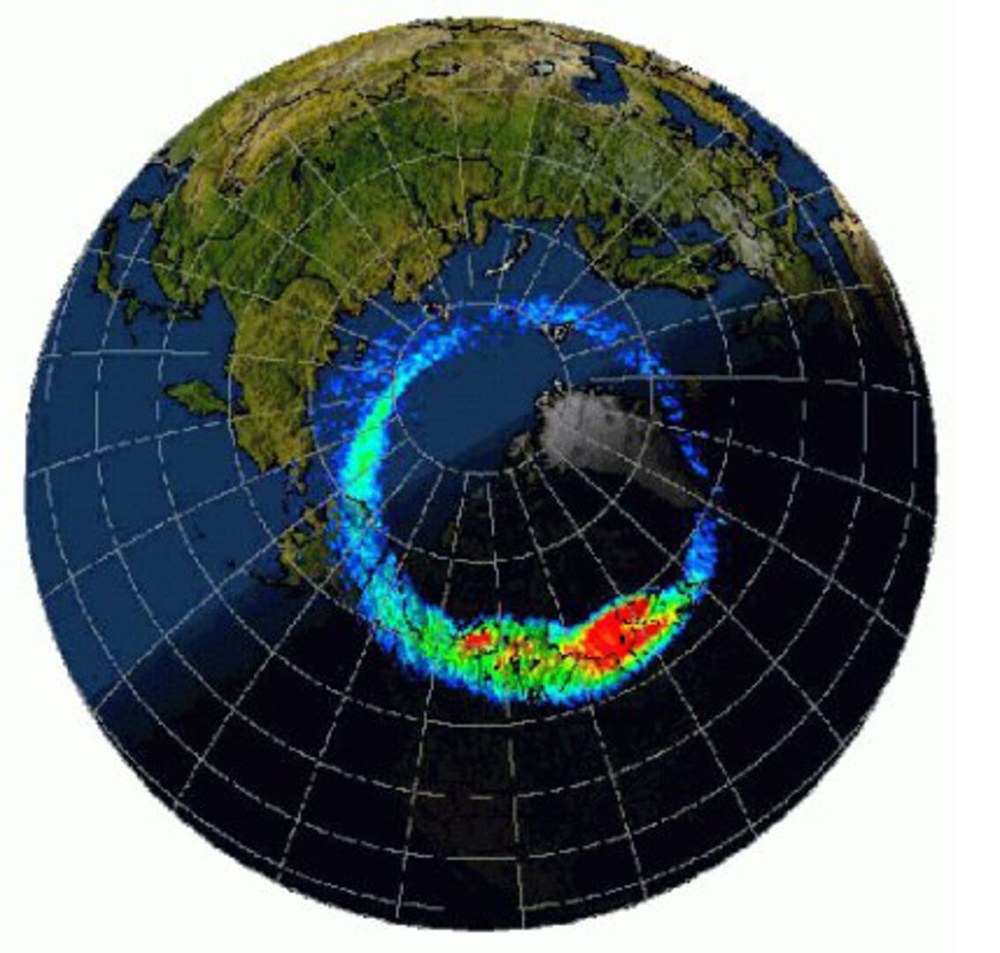

Another common misconception is that the Northern Lights are best observed directly at the North or South Pole. Auroras do not necessarily become more frequent the closer you get to the poles. The phenomenon occurs mainly in a ring, known as the auroral oval, which is centred around the geomagnetic poles rather than the geographical poles. The geomagnetic North Pole is currently located at approximately 80 degrees north, near Ellesmere Island in Canada. For this reason, auroras extend farther south in North America than in Europe.

During periods of normal solar activity, the auroral oval is positioned at approximately 60 degrees north over North America and around 70 degrees north over Europe. The Norwegian city of Tromsø is often referred to as the Northern Lights Capital of Europe. However, during geomagnetic storms, the auroral oval may expand southward. In October 2024, for example, auroras could be seen in the northern sky even at central European latitudes.

A clear, cloudless sky and the darkest possible observation site are crucial to see auroras. In large cities, artificial lighting significantly brightens the night sky – an effect known as light pollution – making them much harder to observe in urban areas.

To see the aurorae, a cloudless sky and the darkest possible location are crucial. In large cities, artificial lighting significantly brightens the night sky – an effect known as light pollution – making it much harder to observe the Northern Lights.