For Remote Sensing Part 1/4 - My first years in DFVLR

Personal reflections on the 40th anniversary

of the German Remote Sensing Data Center (DFD) by Stefan Dech

Introduction

In 2020 the German Remote Sensing Data Center (DFD) celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding.

Today‘s DFD was founded In 1980 – at that time it was the Applied Data Technology facility (WT-DA) – the result of a spin-off from Space Operations in Oberpfaffenhofen. The initiative for the separation came from GSOC’s founding director, Prof. Winfried Markwitz. He recognized already in the mid-1970s that managing and processing payload data from space instruments would increase in importance.

Even at that time, satellite remote sensing in particular was showing its enormous potential, such as for managing the environment. A technical focus quickly emerged: development and operation of systems to process data collected by satellites for purposes of earth observation. And this undertaking soon led to a name: in 1993 DFD received its present name, also externally. Since that time DFD has changed in many respects. And at the same time it has remained true to its original mission: our specialist DNA of the early years still determines large parts of today’s portfolio of tasks. And colleagues from the early years are still active and continue to shape DFD’s culture of creativity, reliability and pragmatism. But DFD became a “special” institution – also by international comparison – Only after subsequently developing its combination of engineering, information technology and geoscience competence. Today, technology and research are united under one roof. DFD masters the entire remote sensing systems chain, from initial data acquisition to final analysis using its self-developed Open-GIS environments.

On this anniversary, Stefan Dech – DFD director since 1998 – reflects on important developments up to the present time from a totally personal perspective.

At this point part 1 of four parts follows.

PART 1 - My first years in DFVLR

I am sitting in the office of my geomorphology professor Detlev Busche in Würzburg during the 1985 summer semester. I had recently completed his course in assessing aerial and satellite images, which had fascinated me. Analysed stereo aerial images of Würzburg under a stereoscope, and then produced a thematic map (still analogue, of course) based on a US-American Landsat multispectral composite showing land use in a region of Lower Franconia. My enthusiasm for remote sensing was roused. At that time, remote sensing was only starting to be a subject to teach. Mostly, one had to learn autodidactically. In any event, I was certain that this was the direction in which I wanted to develop competence. Despite the fact that until then, as a “physical geographer” I had especially enjoyed climate geomorphology. This field had a fine tradition right there in Würzburg thanks to research by Julius Büdel, one of the great concept developers and teachers of that time. I soon found out that a European space organisation (ESA) that also acquired satellite data was based in Darmstadt. I mentioned to Prof. Busche that I wanted to apply for a traineeship there.

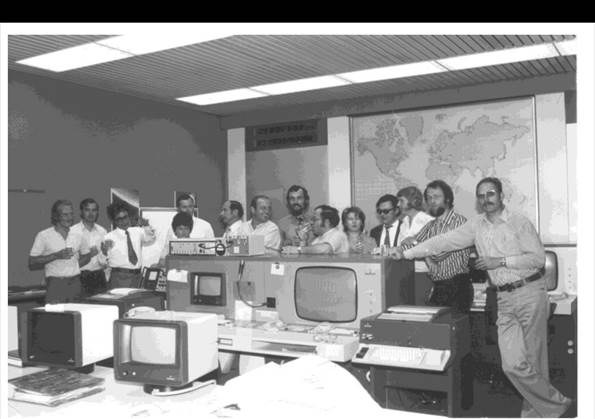

“No, I think there’s something better…”, he answered. “…there’s the DFVLR in Oberpfaffenhofen near Munich; they also do a lot with remote sensing, but with much more emphasis on applications.” Starting in 1986 one could even process there the new 10 m resolution data from the French SPOT-1 satellite. “And they market Landsat data also for Germany.” After my application for a traineeship finally landed on the desk of Dr Rudolf Winter in the Applied Data Technology facility after a detour to Dr Franz Schlude at GSOC, a better-known facility, I indeed received an offer of a traineeship in his department starting in March 1986. And so I was at the gate on March 1st and a short time later addressing Margot Pfeil in Dr Winter’s outer office. I was assigned to a very energetic doctoral candidate in the “forest project”: Mathias Schardt, today a professor in Graz and a director at Joanneum Research. And that’s how my professional adventure began at DFVLR – at the German Remote Sensing Data Center!

My first years as a post-graduate student

After my internship I could return in summer as a diploma candidate and work on my own topics. In 1987 – after my diploma certification – I had the chance to continue working as a doctoral candidate. I hadn’t dared to hope for that opportunity. In the department of Dipl.-Ing. Jörg Gredel I worked with US-American NOAA data and analysed sea ice movement in the Arctic. Participation in an international campaign in 1988 in Spitzbergen was my first professional highlight. I was still a greenhorn among all the seasoned scientists from Germany and abroad. But already at that time I received support from elder colleagues. Especially Dr. Peter Wendling of the Institute of Atmospheric Physics helped me with the rather complex flight planning for my aerial surveys. The AVHRR data recorded several times a day and used to plan the flights undertaken during the ARKTIS 88 campaign – DFD had erected a receiving station at the Longyearbyen airfield especially for that purpose – were also the basis for my ice drift analyses. At that time this had never been done at such high temporal resolution. I could also join two flights with the Falcon and the DO-228 CALM (pilots were the unforgotten old troopers Helmut Laurson and Peter Vogel) over the eastern Greenland Sea and other locations to produce my own reference images of the edge of the sea ice using two Hasselblad cameras. They were supposed to be stereo images so that the roughness of the ice could be judged, but one camera was defective (which I didn’t notice at the time), and weeks later all the images I took with it emerged as perfect “night images” at WT-DA’s own photo lab run by Wilfried Huss. What a relief that at least the second camera had functioned perfectly!

Already at that time I experienced DFVLR as an almost “fairy-tale” place with opportunities that were hard to find elsewhere. What delighted me from the beginning was that there was almost no question in the realm of natural sciences, technology or informatics that couldn’t be answered by at least one colleague. The accumulated knowledge was very great already at that time, and I think it has become much more extensive since then.

At this time I was only interested in remote sensing and passionate about new data and results. Especially at night – to the dismay of the guards on duty – we doctoral candidates had a green light and could use the limited resources (which were indeed enormous, considering what was then standard). I worked with a Perkin-Elmer computer system with removeable magnetic drives for data storage and various software packages, most of them in-house developments, like DIBIAS and ISM. Late in the evening batch jobs were set up, and the next morning one could hardly wait to see the results. I spent hours, days, weeks and months in front of monitors. At that time they consisted of a console for entering ASCII-commands, a small control monitor that showed all the jobs on the Perkin Elmer, and an additional system for interactive image output. With a trackball instead of a mouse, of course. There was also a TV monitor showing a live image of the computer room. That was very practical since one could then see whether commands to input data were actually being carried out. That was easy to see because of the rapidly rotating, CCT tape drives.

I had no idea whatsoever of the difficulties of leading a department, far less a facility or an institute. And the DLR Executive Board was far, far away – like Neil Armstrong on the moon. But all that was to gradually change…

Beginning professional life

Shortly before completing my doctorate I was surprised to be asked by our director, Prof. Winfried Markwitz, to come for a personal conversation. I was quite nervous when the time came and I was sitting in his new office on the 2nd floor of building 121, then called the User Data Center, UDC, and just beginning operations in 1989. Mr Markwitz asked what I was planning to do after I had my doctorate, and whether I would consider staying on. What a question! Then he asked whether I had heard about the construction of a receiving station in the Antarctic (GARS O’Higgins). Some understanding of polar research topics would be required, and close contacts with the national polar research community would need to be cultivated as well. Time would surely also be available for one’s own research interests.

It was like winning the lottery. And the bonus number as well!

So I transferred to my third WT-DA department before completing my doctorate. My path had led from Remote Sensing Applications DA-FE (Winter) to Information Systems DA-IF (Gredel) to Satellite Data Acquisition“ (DA-SN) and a new superior, Dr. Klaus-Dieter Reiniger. He was regarded as highly experienced, well-tested also under the difficult first years of MORABA abroad, and at the same time also feared because of his direct manner. But that rough exterior masked a very amiable and reliable person. Later, more connected us than our professional collaboration. From 2001 until he retired in 2006 he was also my deputy as director of DFD.

Very soon Wolfgang Balzer (as engineer) and I (as a user of remote sensing) were deputizing for Klaus Reiniger. Klaus Reiniger and Winfried Markwitz gave me a free hand in putting into practice my first ideas about not only generating standard products at the ground segment but also regularly deriving geoscientific content from the data, in other words, to engage in value-adding. I was able to experiment with the data collected by the AVHRR sensor on NOAA satellites, which I was quite familiar with. What today is a matter of course was at that time rather unusual, considering the conceived focus of DFD. Remote sensing data was primarily used in projects, and thus within rather limited temporal and spatial ranges, and the processing was carried out by the users. My goal was to generate time series that contained decades worth of data so that developments could be identified and causes and effects investigated. And also to make computer animations of the emerging time series in order to draw public attention to DFD.

With this idea – launched with the designation Feature Data Base– I could set up my own working group, named Value Adding and Visualization. By 2006 this group had grown to include eight colleagues. Together with Thomas Ruppert, already at that time a brilliant programmer and IT nerd in the best sense of the word, we cleared a number of hurdles to build up a system. Fortunately, he became interested in my ideas, in addition to his main task of testing a specific DMS system for ERS-1. We procured US-American software, including a small X-band receiving system under a radome. Both came from the SeaSpace company in San Diego, California. This was because the period when we could create our own software for image processing was definitely coming to an end. It required too much effort to keep up with emerging industrial products, and the development work was too expensive. We worked with NOAA data acquired in-house, and later also with Terra/Aqua data. As to content, we concentrated on time series of sea surface and land surface temperatures, vegetation indices, and, starting in 1995, also on ozone data from the GOME instrument on ERS-2. In due course we could generate the first time series in 1992, as planned, and – after I could recruit Robert Meisner for my group – a short time later also the first animations.

That was probably my most carefree time at DLR: We were free to tackle intriguing projects of our own, like the development of a near-real-time processing system for analysing ERS-1 SAR-data at BSH, assessing military hazardous waste in the newly formed German states after reunification using hyperspectral DAEDALUS data, and analysing the progressive desiccation of the Aral Sea. We never had a chance to become bored. And literally talked into it by Winfried Markwitz and Prof. Horst Hagedorn, who had the chair of physical geography in Würzburg, I began to work on my post-doctoral thesis, which I could finished in 1997.

This was also the time when major internal transformations were announced. After an outstanding formal assessment in 1993 the Applied Data Technology facility was from then on officially renamed, also externally, the German Remote Sensing Data Center. WT-DA became DFD. This was yet another strategically important, landmark decision of our director Winfried Markwitz. The goal was, as an institution of the DLR, to assure the supply and long-term availability of remote sensing data for the national user community. Because of our good assessment we were provided with additional staff positions to further strengthen DFD. After Rudolf Winter accepted a position at the EU as director of the Space Application Institute in Ispra, Italy, Winfried Markwitz appointed me Rudolf Winter’s successor in 1996 as head of the Remote Sensing Applications department and I integrated my own working group from Klaus Reiniger’s department into this new expanded context. The portfolio of the original remote sensing department “FE” has up to the present expanded into four independent DFD departments working in remote sensing and georesearch as well as computer animation: Atmosphere (Prof. Michael Bittner), Land Surface Dynamics (Prof. Claudia Künzer), Georisks and Civil Security (Prof. Günter Strunz) and Science Communication and Visualisation (Dipl.-Geogr. Nils Sparwasser). Today ca. 120 staff members are employed in this field.