What Tower?

The air traffic control tower is often the most striking structure of any airport. From its commanding position, air traffic controllers have everything in view – well, almost everything, because there are blind spots, which is why larger airports in particular are now monitored using a wide variety of sensors. But the 'Remote Tower' concept goes further – it uses optical sensors to deliver video images that replace the direct view from the tower window. These video images do not necessarily have to be displayed where they are captured, meaning that airports can be controlled remotely. In a 'Remote Tower Centre' it is even possible for the sensor data from several airports to come together, which can make air traffic control (ATC) much more efficient and flexible. The first Remote Tower Centre was opened in Sweden in 2015. Since 2018, airports have also been monitored from afar in Leipzig, while in the year after next a centre is scheduled to open in Braunschweig, in the immediate vicinity of the place where the concept originated 20 years ago – the DLR Institute of Flight Guidance.

The story of the Remote Tower began in 2001, when a team from the Institute of Flight Guidance entered the idea of a remote or 'virtual' tower from which air traffic control at an airport could be operated, to an internal DLR competition. The concept drew upon work by the NASA Ames Research Center, which had already conducted research into the use of virtual and augmented reality applications for air traffic. The idea, visionary at the time, won the competition and received an award. The team then set about developing an initial prototype to show how the concept might work in reality. Since 2005, the system was tested at Braunschweig-Wolfsburg Airport. At the same time, the world's first remote tower simulation was created at the DLR Institute, in the form of a live 180-degree digital video panorama. National and international research and development activities followed, prompting numerous air traffic control organisations such as the Swedish Civil Aviation Authority and the German air navigation service provider Deutsche Flugsicherung (DFS) to express their interest.

An idea that works

In 2014, DLR was able to transfer the technology to industry. The team not only made advances in technology, but also developed methods to examine and improve the interaction of ATC personnel with the new technology. The first Remote Tower finally went into operation in Sundsvall, Sweden in 2015. Since then, all air traffic control operations for Örnsköldsvik Airport have been operated from Sundsvall. "This success helped us to think further. If we can control one airport remotely, it should also be possible to control several airports from a single working position," says Jörn Jakobi of the Department of Human Factors at the DLR Institute of Flight Guidance. This was the birth of the Multiple Remote Tower concept, the core idea of which is that a single air traffic controller can monitor several airports simultaneously. This is now to be tested at the new Remote Tower Centre (RTC Lower Saxony) in Braunschweig, which is being set up by DFS Aviation Services (DAS) and is scheduled to go into operation in 2024. To this end, DAS and DLR will work together in an affiliated research cluster to further develop the concept. "Of course we'll start with one controller working at a maximum of one airport," says Jakobi. In the next step, low-traffic airports will be interconnected on a trial basis. In this way, the controllers will be able to gain hands-on experience with the new technology and adapt to the new situation.

A panoramic view, despite the distance

Then, as now, the high-resolution video panorama is the heart of the Remote Tower. This is where the controllers sit and survey the various airport areas. An array of cameras installed in a row generates the panorama on site. In addition, pan and tilting zoom cameras bring every detail into view. In order to investigate various scenarios, the DLR Institute has set up a Remote Tower laboratory that realistically depicts this working environment. "We can just as easily simulate large international airports with several controller workstations, as smaller airports or airfields. We can also deliberately simulate emergency situations such as a burning engine, a problem with the landing gear or deviations from clearances. In doing so, we can test whether or not the controller notices the critical situation and if and how it can be resolved," says Jakobi. For RTC Lower Saxony, the 'twin' of a real workstation is also being set up at DLR, fed with all the important operational data from the airport. This makes it possible for new techniques and processes to be researched in parallel with real operations.

Safety comes first

Before innovations are tested in live operation, extensive simulation trials are carried out. During the tests, different controllers work on the same traffic scenario one after another in the simulator, alternating between the old and new technology. The researchers study the workload to see if it has increased or decreased, and observe how well the participants have grasped the situation in which they find themselves. They are asked whether they can predict how traffic conditions will develop and whether they have the necessary tools to handle critical situations. "We need to ensure that the new system will add value, meaning that it is either safer or more efficient, before we even consider bringing it to market. Under no circumstances should it be less safe than the original system," says Jakobi. A psychologist, he is the project manager responsible for the Remote Tower concept. Acceptance is also of great importance; if the users aren't behind the concept, it will probably not become established practice. For this reason, the scientists seek out practical feedback at an early stage.

"We need to ensure that the new system will add value, meaning that it is either safer or more efficient, before we even consider bringing it to market."

Jörn Jakobi, DLR project manager Remote Tower

A matter of balance

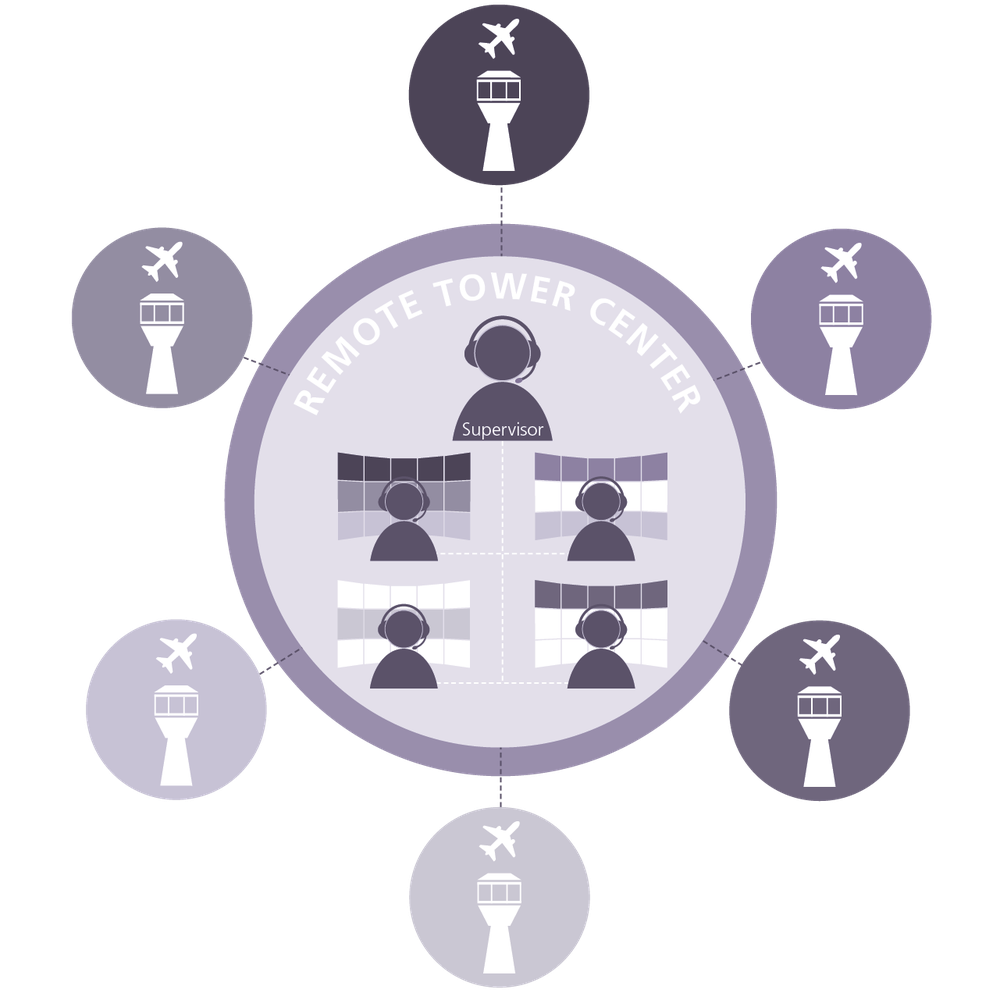

Stress levels are an important indicator for evaluating the safety of the system. A high workload is nothing unusual, especially in air traffic control. In the long run, however, it can lead to negligence and errors. Meanwhile, an under-load can also have fatal consequences. "Someone who is only observing and doesn't have much operational work to do may well be unprepared when something critical does happen and unable to react appropriately," says Jakobi. Normally, controllers work according to the four-eyes principle, meaning there are always two people on duty to support each other. In a Remote Tower Centre, several air traffic controllers, each monitoring an airport alone, are supported by a supervisor. If necessary, this supervisor provides the second pair of eyes.

The supervisor also plays a crucial role in the Multiple Remote Tower concept, by monitoring and distributing the workload. To this end, the DLR team is researching a suite of new digital planning tools that allow everything to be kept in view. If the workload is poorly balanced or becomes critical, the system issues warnings and helps to find suitable support. The system was put to the test at the end of 2021. Here, DLR, together with industrial partner Frequentis, set up a Remote Tower Centre prototype from which Lithuanian and Polish air traffic controllers monitored a total of 15 simulated airports remotely.

"This is particularly interesting for airfields with very little traffic or at night, when no air traffic control is currently provided for financial reasons or staff shortages, and those airfields close," explains Jakobi. In future, a controller could be on duty at the centre in such situations to monitor the airports during this time, thus extend their operating times and increasing their attractiveness to passengers and cargo customers. This in turn could increase demand and thus generate more revenue. "The result is a needs-based air traffic control service for the entire airport network and synergy for aviation," adds Jakobi.

Enabling more traffic at smaller airports

The German air navigation service provider DFS coordinates operations at Germany's 15 international airports. But there are a total of around 400 airfields in Germany. At small airfields, there are often Aerodrome Flight Information Service officers who provide information but do not carry out air traffic control. Here, pilots have to fly according to Visual Flight Rules and mainly coordinate amongst themselves. Commercial instrument flying cannot take place. "When such small airports join together in a RTC, they can save resources and offer more qualified ATC services at a reasonable cost," says Jakobi.

This will also be tested by RTC Lower Saxony. Certified air traffic controllers will sit next to Aerodrome Flight Information Service Officers (AFISO) serving Emden Airport. A first research question will be to examine whether air traffic controllers and AFIS personnel can be flexibly switched between the workstations, and which problems still need to be solved. Jakobi sees a key advantage of the technology in the fact that it makes aerodrome air traffic services much more flexible: "With quick availability and flexible working, the entire air traffic service system becomes more versatile and adaptable to current conditions."

What will the future bring?

So will the airports of the future be towerless? "At many small airports, remote towers will sooner or later become the norm," says Jakobi. Rather than investing in expensive new buildings or maintaining existing towers, investment could be redirected to sensor technology, which is much more economical. This was a decisive argument for Saarbrücken Airport, where the tower was going to be renovated at great expense. Today it stands empty, and coordination takes place at the Remote Tower Centre in Leipzig. The Scandinavian Mountains Airport near Rörbäcksnäs, Sweden, which opened in 2019, was planned and built with no tower at all. However, already existing towers would not have to be demolished. For example, they could serve as a fallback option if problems arise in the centre. In addition to such alternative options, the Remote Tower concept has redundancies built into to it to cope with failures.

For Jakobi, the success of the Remote Towers has a lot to do with close cooperation: "Users, research and industry must come together as early as possible – one providing the requirements, another the research expertise, and the third the ability to develop and sell the marketable product." In Germany, a fourth player is the Federal Supervisory Authority for Air Navigation Services (BAF). This office is tasked with examining and approving new concepts, and DLR remains in close contact with it. Before the opening of the Remote Tower Centre in Leipzig, DLR experts contributed research results to a report, on the basis of which the BAF approved the operation. DLR is also represented on international committees for the standardisation of Remote Tower concepts, helping to continue this success story and a start a new chapter in aviation history.

An article by Michael Drews und Julia Heil from the DLRmagazine 171