No stone unturned

"That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind." Many are familiar with the most famous words spoken by Neil Armstrong on the Moon on 20 July 1969. But the last words radioed from the Moon to Earth have a certain historical significance, too. They were spoken by Eugene 'Gene' Cernan, Commander of Apollo 17. Before boarding the lunar module almost 50 years ago, on 14 December 1972, he said, "and as we leave the Moon at Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17!" Some four days later, one of the greatest adventures of humankind, the Apollo project, came to an end when the Command Module America splashed down in the ocean.

The milestones and extreme feats of this daring endeavour, announced in 1961 by the US President John F Kennedy, are legendary. Between 1968 and 1972, 24 men left Earth's orbit (the only ones to do so to date). Twelve of them left their footprints in the dust of Earth's natural satellite over the course of six successful Moon landings. They all came back alive, even the crew of Apollo 13, which was saved following an oxygen tank explosion when they were two-thirds of the way to the Moon. The astronauts Virgil 'Gus' Grissom, Ed White and Roger Chaffee, who were tragically killed in a fire in the Apollo Command Module during a preflight test at Cape Canaveral in 1967, will also be forever remembered.

The end of 1972 marked the conclusion of Apollo, even though three more missions had originally been planned, the destinations selected and the launch vehicles built. President Nixon made the decision in 1971, deeming the programme too expensive. He also feared that there was too little political advantage to be gained from the remaining three missions. NASA did not put up much of a fight. Those in charge were extremely pleased with the results up until that point, especially as all of the astronauts had returned safely, and six crews had delivered a rich treasure trove of Moon samples and technical and scientific knowledge to Earth.

The first scientist in space

This scientific bounty was especially plentiful over the last three missions – the three 'J' missions, each lasting three days on the Moon: Apollo 15, 16 and 17 – as these lunar flights were primarily dedicated to scientific goals. The initial motivation for putting a US-American on the Moon had been a political one – to get there before the Soviets. The goal was to demonstrate the superiority of the free Western world. Nevertheless, these efforts were also accompanied by a scientific programme. To make sure that the first human on the Moon would literally have solid ground to walk on, Earth's satellite was explored beforehand using robotic probes. From the outset, the scientists involved recognised the importance of the Moon for our understanding of all four Earth-like planets. With a surface that is over three billion years old, the Moon provides an insight into the early days of the Solar System. The scientists devised numerous new experiments for Apollo 11 and the five subsequent landings, and provided scientific training for the astronauts. During this process, 11 test and Navy pilots became keen and highly trained lay scientists.

For the final mission, a 'real' scientist, geologist Harrison 'Jack' Schmitt, was selected, with the aim of even further increasing the scientific yield of the mission. Alongside the rest of the Apollo 17 crew, Schmitt thundered into the night sky over Florida on 7 December 1972. The launch of a Saturn V is said to be the loudest noise ever created by humankind. Half a million people watched the spectacle.

Planetary research has reaped the benefits

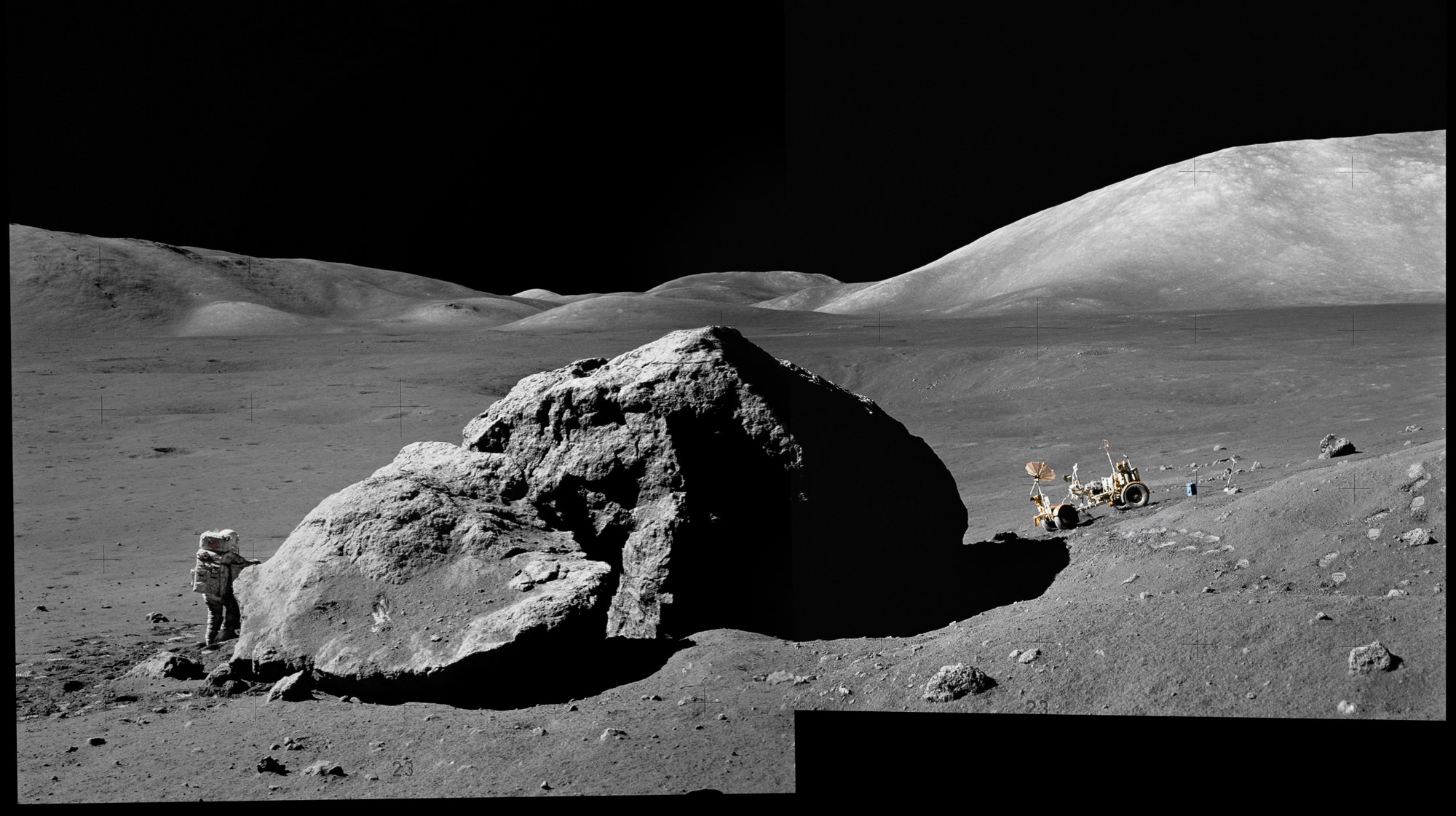

The lunar landing four days later ran like clockwork; even the high mountains around the Taurus-Littrow valley did not present any obstacle for Schmitt and Cernan. The two spent three days and three hours on the southeast edge of the Mare Serenitatis – the easternmost of all landing sites – which is filled with volcanic rock. This area was chosen to study a relatively old impact basin. The 3.8 billion-year-old Imbrian Basin that dominates the near side of the Moon had been studied several times on previous missions.

Over three trips with the lunar rover, each lasting more than seven hours, the two astronauts covered 34 kilometres. By the time they were done, they had stowed 110 kilograms of Moon samples in the Challenger. Ron Evans, the command and service module pilot, examined the Moon from orbit using cameras, spectrometers and – for the first time – radar. He holds the orbit record, having flown around the Moon 75 times. Upon their return, the NASA scientists did not know whether to feel sad about the premature end of the Apollo era or rejoice at the scientific and material yield from all of the experiments at the landing site, on the excursions and from orbit. Examining the samples and evaluating the data was the work of decades; indeed, it is still ongoing. The findings fill volumes. Apollo was history. Bill Anders, who circled the Moon with Apollo 8, the first 'lunar' mission in the programme, and who took the famous Earthrise photo in 1969, beautifully sums up the key insight from the whole endeavour: "We set out to explore the Moon and instead discovered the Earth."

An article by Ulrich Köhler from the DLRmagazine 171