From Babylon to Broadband

Thomas Gessner/MSPT

Many of us take instant and unrestricted communication for granted, but the nature of communication is always changing, across time and around the world. At the Museum of Communication Frankfurt, visitors experience the history of the place where technology and society come together, one which has been posing humankind the same challenges for millennia.

The story of communication is the story of who is allowed to speak, what they are allowed to say, and who is allowed to listen. It is the story of new technologies and new users – from Hammurabi's code to Gutenberg's printing press, Marconi's radio to the Telstar 1 telecommunications satellite. It is also the story of increasing efficiency and speed, how we have always tried to say more with less, and faster than ever before. Ideas became 1700 hieroglyphs, which became two dozen letters, which became bytes and radio waves. Each new technology requires new skills, from hard skills such as literacy and digital literacy, to poetic and persuasive soft skills that increase their effectiveness.

The exhibits at the Museum of Communication Frankfurt are not just records of how contemporaries communicated with each other. The Frankfurt 'Brieffund' – a collection of local letters from the sixteenth century – offers a window into the lives of the past, an act of communication across time to the visitor. While we may consider the way we craft an image of ourselves and present it to the outside world as a phenomenon inherent to modern social media, these letters, combined with the museum's collection of love letters written by Goethe and Kafka and telegrams from Titanic passengers, reveal that the struggle to control how the world sees us, our thoughts, feelings, fears and desires, is not as new as it seems.

Markets and monopolies

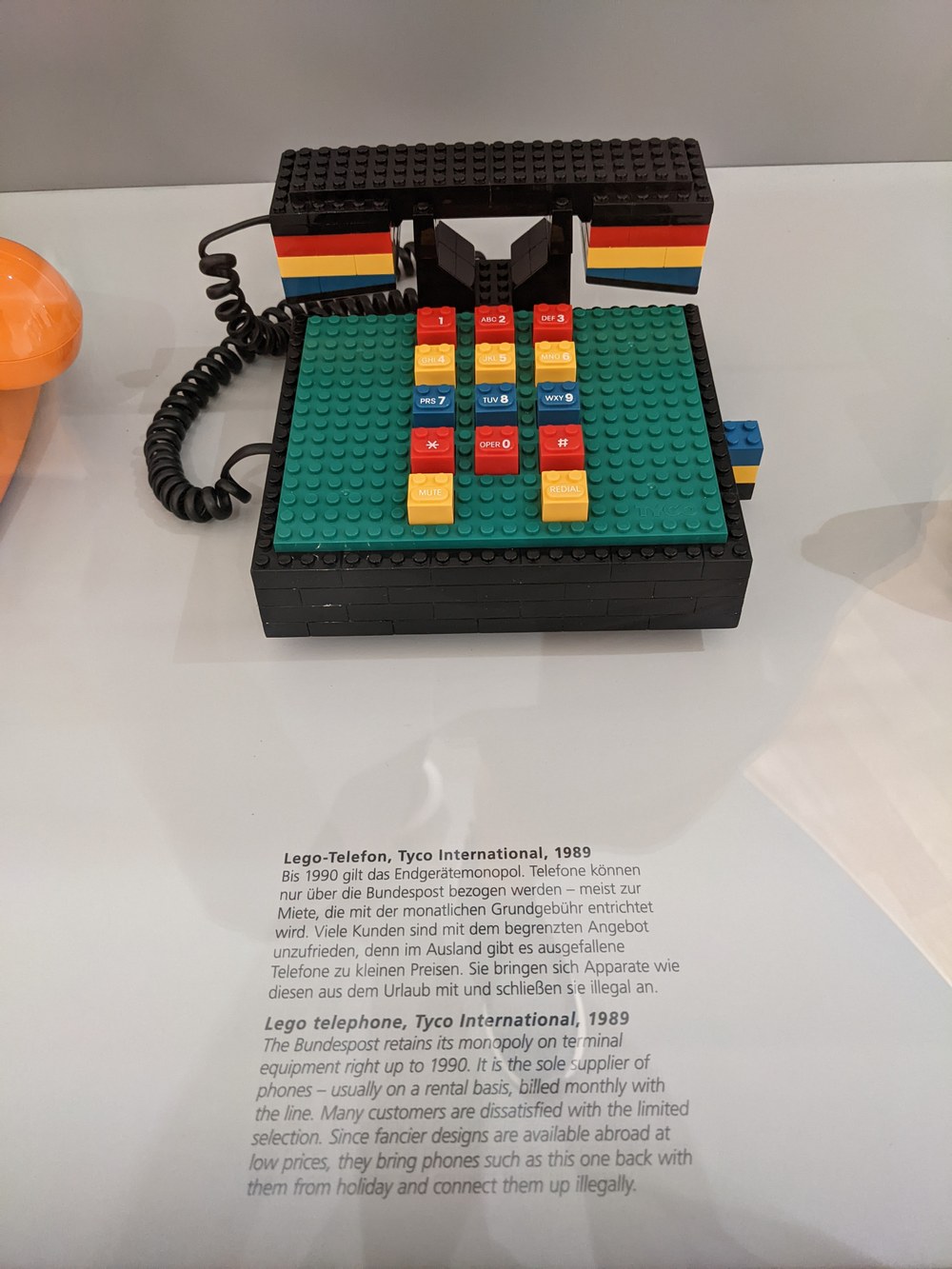

Another common fear connected to social media is that of monopoly – that a small number of entities may have too much control over the infrastructure we use to communicate. But this too, is far from a new phenomenon. In the early 1900s, the United Kingdom had an effective monopoly on undersea cables used to communicate across the Atlantic, while the Deutsche Bundespost possessed a monopoly on home telephones in (West) Germany until as late as 1990.

J. Tapley

Rather than set humankind on a clear trajectory towards a better or worse society, the museum makes it clear that new communication technologies seem to amplify both the best and the worst of us. The only constant trend seems to be how increasingly important and everpresent these technologies become in our everyday lives. The more communication is censored, the more people rebel; the stronger a monopoly, the more people turn to piracy. Germans circumvented the Bundespost monopoly on telephone sets by purchasing and smuggling illegal foreign models into the country, while citizens of the Soviet Union demonstrated the freedom in their bones by carving records of forbidden folk songs and Elvis Presley hits onto used medical x-ray film. You can listen to recordings at the museum.

Trust and transactions

Like an Elvis record in an underground Soviet music club, we seem to be stuck on repeat. The internet may be the current culmination of our need to communicate more and faster, but it also brings with it some age-old challenges and concerns over trust, privacy, freedom, security, control and monopoly into the digital age. Even data privacy and fake news are not new concerns. Census data about race was collected and used by the National Socialist regime in Germany and broadcasts proclaiming the exaggerated success of recent war efforts are as old as radio itself.

J. Tapley

The story continues

The museum is an impressive effort of communication in its own right. It brings the history of communication to life through a combination of bilingual written content, imagery, models, sounds, demonstrations, antiques, anecdotes and games. It has a lot of fun activities for children and adults and is very affordable. The staff are friendly and knowledgeable and offer a guided tour to all guests, but you are also free to make your own way around. For those choosing to go their own way, the museum would benefit from a clearer indication of the chronological order of the exhibits.

The museum also contains a permanent exhibition featuring 21 video messages from experts on a range of topics: Will we have to buy our privacy in the future? How will we communicate 30 years from now? What is the future of human-machine interaction? Will virtual reality workplaces become commonplace in an age of increasing remote work? The exhibit marks a nice way to end a visit to the museum and the wonderful and worrying possibilities for the future will leave you with many things to think about on your way home.

Just like the Frankfurt 'Brieffund', maybe these video messages will find their way back into the museum centuries from now. Future visitors may learn about how we communicated in the twenty-first century, about our hopes and fears. Perhaps they will even stop to consider whether they themselves are still facing the challenges we faced from Babylon to broadband.

Museum of Communication Frankfurt

J. Tapley

Address:

Schaumainkai 53,

60596 Frankfurt am Main

Telephone:

+49 069 6060-0

Admission:

Adults: 6 €

Reduced admission: 4 €

Children, youths: 1.50 €

Children up to five years: free of charge

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Sunday 11 am - 6 pm

Wednesday 10 am - 8 pm

mfk-frankfurt.de

An article by Joshua Tapley from the DLRmagazine 171