Getting the 'Göttingen Egg' rolling

Even if the name does not necessarily suggest it, transport research at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) has a long history. The Aerodynamics Research Institute (AVA) in Göttingen and the German Institute for Aviation Research (DVL) in Berlin-Adlershof were both testing cars in wind tunnels during the 1920s and 30s. But what happened when aircraft manufacturers started building motor vehicles?

Following the entry into force of the Versailles Peace Treaty in 1919, aeronautical research, flights with powerful engines, and the construction of aircraft engines were prohibited in Germany. As a result, aeronautics research institutions and aircraft designers had to seek alternative sources of income. Consequently, several aircraft manufacturers, including Edmund Rumpler (1872–1940), switched to automobile construction. They benefited from their aerodynamic knowledge, which could also be transferred to motor vehicles.

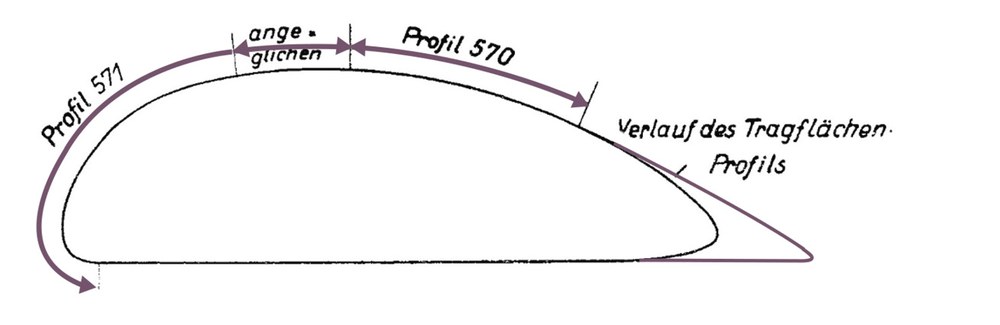

Rumpler designed the Rumpler-Tropfenwagen (Rumpler raindrop car), which had a droplet shape when viewed from above, enabling it to achieve a low drag coefficient (Cd value). A model of Rumpler's car was tested in the AVA wind tunnel around 1920. In the years that followed, companies such as Daimler approached AVA to have racing car models systematically analysed in the wind tunnel. In this way, AVA developed a new field of research. In 1935, it received an order from the German Ministry of Transport (RVM) to develop a so-called semi-streamlined car – a vehicle with a streamlined tail.

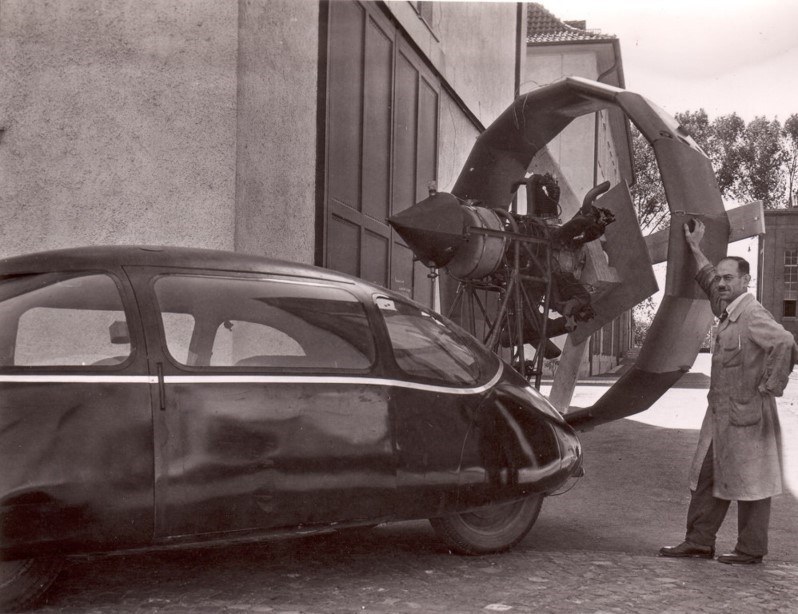

Once the model had been tested in detail in the wind tunnel in Göttingen, AVA received a follow-up order from the RVM to design and construct the prototype of a fully streamlined vehicle. Such vehicles were characterised by streamlined features at both the front and rear. Engineer Karl Schlör (1910–1997) was entrusted with this task. Initial experiments with a model in the wind tunnel showed that the new body shape had a significantly lower drag coefficient compared to the conventional, box-type vans that were common at that time.

Forever streamlined

The next step was to build the model at full scale. In order to keep the drag coefficient as low as possible, Schlör made sure that the wheels of the car were surrounded by the bodywork and that all protruding components, such as door handles, indicators and headlights, were recessed into the body. Since commercially available chassis were too small for this streamlined body, Schlör disassembled the chassis of a Mercedes-Benz vehicle with a 1.7-litre rear engine and welded the individual parts back together in a modified arrangement. This resulted in a steering column located in the centre of the car. At the rear, there was space for up to six passengers across two rows of seats, arranged one behind the other.

Since the AVA had no experience with vehicle body construction, they commissioned the Ludewig Brothers company in Essen to build the 'AVA test car'. It was later dubbed the Schlörwagen or the 'Göttingen Egg' due to its distinctive shape. Schlör transferred the car from Essen to Göttingen at the end of 1938.

There, the car was analysed in the wind tunnel. Its average drag coefficient was just 0.186. For comparison, in modern cars, this value is between 0.22 and 0.35 (up to 0.4 in SUVs). Initial measurements of the drag coefficient during test drives on the motorway between Göttingen and Kassel resulted in values of around 0.189, which did not particularly surprise the experts given the car's systematically streamlined design.

Desire and reality – top speed

However, the maximum speed of 146 kilometres per hour, as measured and stated by Schlör in his report, sparked controversy. In particular, renowned motor vehicle researcher Wunibald Kamm (1893–1966) cast doubt on Schlör's statement. He also criticised the AVA test car's susceptibility to crosswinds due to its aerodynamic shape. Schlör was unable to dispel the doubts about his vehicle's top speed. On a test drive on the AVUS motor racing circuit in Berlin, for example, the car only reached 110 kilometres per hour.

The AVA experimental car was exhibited at the Berlin Motor Show in February 1939 – but only outside the gates of the show grounds. A model of the car that was showcased inside the exhibition site had to be declared as merely a test vehicle with no intentions for series production. The Volkswagen Beetle made its public debut at the same 1939 Berlin Motor Show. The RVM wanted to prevent the AVA test car from being perceived as competition. In contrast to the Beetle, the Göttingen experimental car offered significantly more passenger space, higher speed and lower fuel consumption.

With the outbreak of the Second World War, motor vehicle research at the AVA was discontinued. Schlör was subsequently transferred to the AVA branch office in Finse, Norway, and later appointed head of the AVA outpost in Riga. The AVA test car was used for the last time in 1942, when Schlör returned home to Göttingen on leave.

During the final years of the war, the car was dismantled into its individual parts. In 1948, Schlör, now working at the Bavarian State Ministry of Transport, attempted to transfer the car – or what was left of it – from the AVA to Bavaria. However, this failed due to a decision by the British military government, which refused to release the test car. The fate of the AVA test vehicle remains unclear. It can be assumed that it was scrapped at some point, as the body had been badly damaged in 1942, rendering it unusable for further test purposes. Due to its unexplained fate, numerous myths have sprung up around it. Some stories suggest that the Schlörwagen was transported to England after the war, while others propose that it was destroyed during the offensive on Riga. Both accounts, however, have been ruled out since the car was still in Göttingen in 1948. In any case, the vehicle continues to fascinate to this day.

Making recent history tangible

Three questions for Horst-Dieter Görg, a member of the Mobile Welten e.V. association.

Mr Görg, you and other members of Mobile Welten are building a replica of the Schlörwagen. How did you come up with the idea?

We have been investigating the field of aerodynamics for many years. The Schlörwagen was a particularly interesting project, as its drag coefficient (Cd) remains unparalleled to this day. Fortunately, we were able to find partners quickly and establish contact with DLR, within one of whose predecessor organisations the Schlörwagen was developed. And then there is the local connection – our association is based in Hanover, where some of the test drives took place. That makes it doubly exciting for us. Saving energy and streamlining are more important today than ever, and I think we can learn a great deal from the past. We hope that this project will make recent history tangible.

Holger Eggers

You have already built a full-scale model. What comes next?

The model will be on display at the August Horch Museum in Zwickau until the end of October 2023. You cannot drive it, though. In 2019, we discovered three original, albeit dilapidated Mercedes 170 H cars in the Westerwald mountains, which had served as the foundations for the Schlörwagen. We are currently using the parts to build two Schlörwagens in cooperation with the Central Garage in Bad Homburg. The educational value of the model is important to us, so we are keen to make its inner workings visible, perhaps using acrylic plastics or other innovative designs. The frames were rebuilt in 2020 and 2021, and recently our coachbuilder has attached a lattice construction – as a sort of guide for the wooden framework that is yet to be manufactured. Now, you can guess the shape of the outer shell. First, however, we need to raise money for the wooden structure, as everything is funded with donations and personal contributions. The wooden structure will certainly be a challenge for our carpenters, as everything about the Schlörwagen is round and none of the standard profiles are suitable. At the same time, we want to bring the engine back to life; at the moment it is just a collection of parts.

Where will you go first to debut the Schlörwagen?

I would actually like to begin showing it off next year, at a streamlining-themed event in Dessau. The Schlörwagen would fit right in, even if it is only half-finished.

An article by Dr. Jessika Wichner from the DLRmagazine 173