The eternal runner-up

One night! One night was all it took for Simon Marius to make his epochal discovery of moons in orbit around Jupiter. This revelation meant that there were, indeed, celestial bodies with satellites circling a much larger mass – an insight of immense significance. Whilst it did not provide conclusive proof that the Sun – not the Earth – lies at the centre of our planetary system, Marius' telescope observation strongly supported Nicolaus Copernicus' revolutionary idea.

It was January 1610. The mathematician, physician and astronomer born as Simon Mayr in Gunzenhausen an der Altmühl in 1573, had had a telescope for about six months. The first telescopes had been built in Flanders and quickly became indispensable tools for princes and kings, providing a strategic advantage in military campaigns. Astronomers, however, immediately recognised the unmatched value of these devices for their own work. So, they too sought out telescopes from skilled manufacturers or ordered polished lenses to assemble their own instruments of discovery.

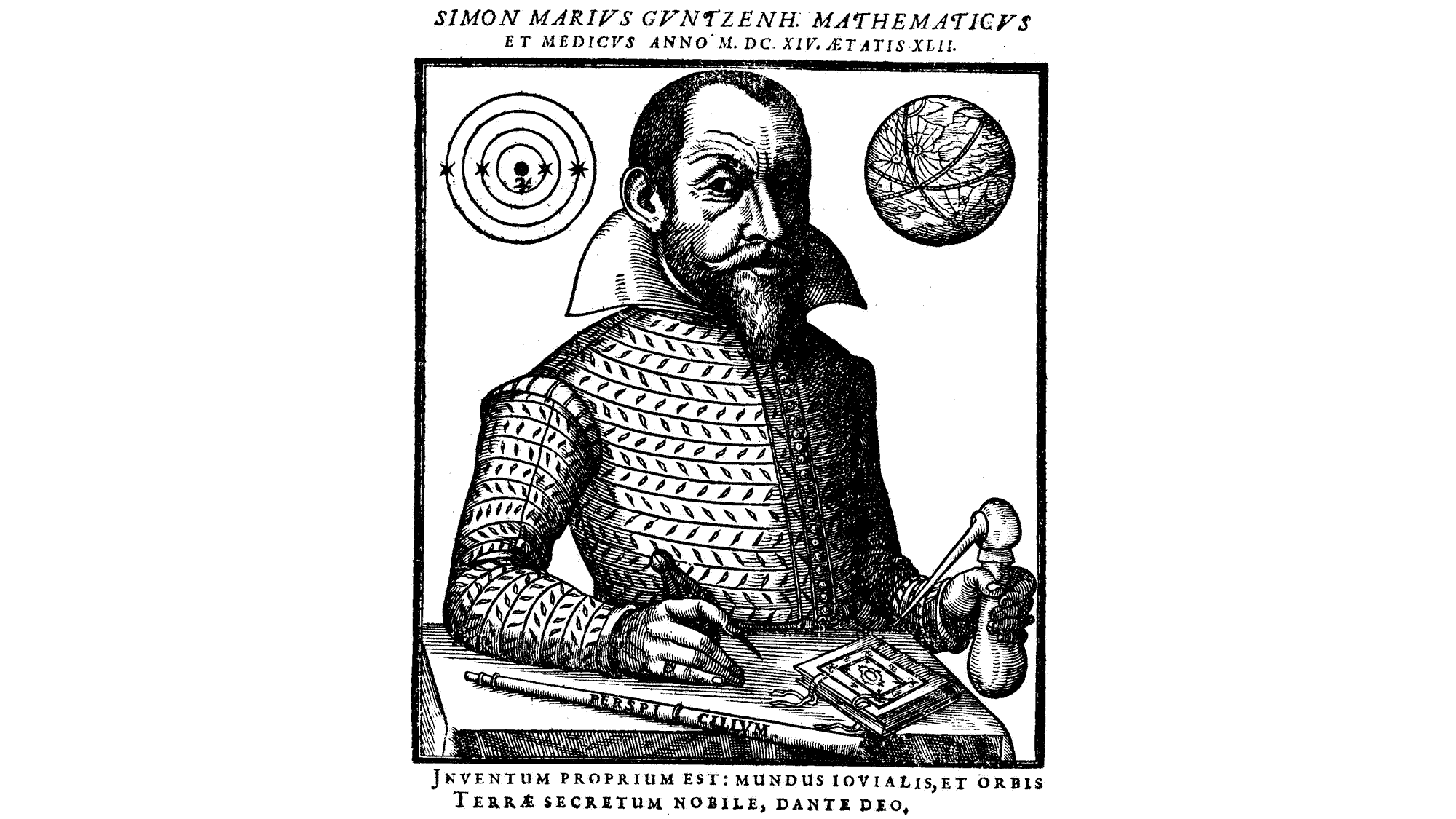

Marius – his Latinised name for the international scientific community – had a natural talent for mathematics and astronomy, eventually becoming the court mathematician for the Principality of Ansbach. His career was also trongly shaped by his time south of the Alps, where he studied medicine in Padua until 1605 and became a medical practitioner.

When Marius met Galileo

It was during this time that he crossed paths with Galileo Galilei with whom he discussed astronomical topics. In 1543, just over half a century earlier, Nicolaus Copernicus had published his life's work, which, from a mathematical point of view, placed the Sun at the very centre of planetary orbits and not Earth, as had been the irrefutable 'law' since Plato.

Like other renowned figures including Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler and Galileo himself, Marius engaged with Copernicus' thesis. However, despite their groundbreaking work, none were fully convinced by their own observations and calculations. At that time, there was no definitive evidence that Earth was moving.

This uncertainty left astronomers grappling with their theories while the clergy loomed, wary of science's slow encroachment on theology. The power of the Church was demonstrated in a chilling manner when Giordano Bruno was burned at the stake in 1600, a stark warning to those challenging established doctrine.

A groundbreaking discovery

In 1606, Simon Marius settled in Ansbach. His early attempts to construct a telescope were unsuccessful due to poor-quality glass. However, in 1609 his patron, Johannes Philipp Fuchs von Bimbach, provided him access to a Belgian spyglass. He pointed it at the planet Jupiter on 29 December 1609, Julian date – in the newer Gregorian calendar it was 8 January 1610. And he saw "… four tiny stars, sometimes behind, sometimes in front of Jupiter, aligned in a straight line with the planet."

Gemeinfrei

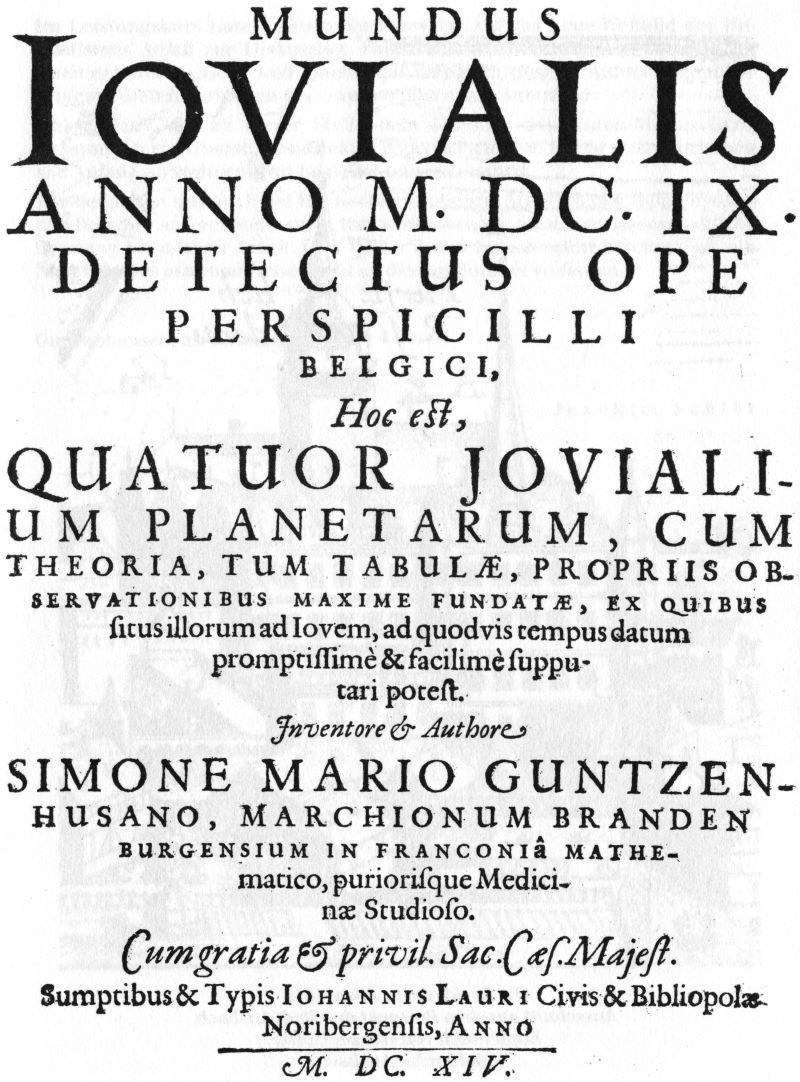

The night before, the night sky in Padua had also been clear. On that very day, Galileo Galilei also observed Jupiter with his recently constructed telescope and made the same discovery as Simon Marius. Unfortunately for Marius, while he made his observations just a day after Galileo, he did not publish them until 1614, in his work Mundus Iovialis (The World of Jupiter). By then, Galileo had already published Sidereus Nuncius (The Sidereal Messenger) – in Venice in 1610 – cementing his place as the first to announce the discovery. Marius' misfortune was twofold; not only did he publish later than Galileo, but his observations had been made just one night after Galileo's. To make matters worse, Galileo, known for his vanity, accused Marius of plagiarism 13 years later and allegedly even 'recommended' him to the Inquisition. Marius' reputation was not fully rehabilitated in astronomical circles until the early 20th century.

Many important discoveries … albeit too late

Simon Marius was, without doubt, a highly respected and esteemed astronomer in central Europe. He made numerous other significant observations of the night sky and the Sun. However, for the timings of his discoveries, history has not been kind to Marius. Time and again, it turned out that someone else had already made the same findings – whether consciously or unconsciously. This misfortune characterised, for example, his observations of the phases of Venus, Andromeda – the neighbouring galaxy to our Milky Way – and more.

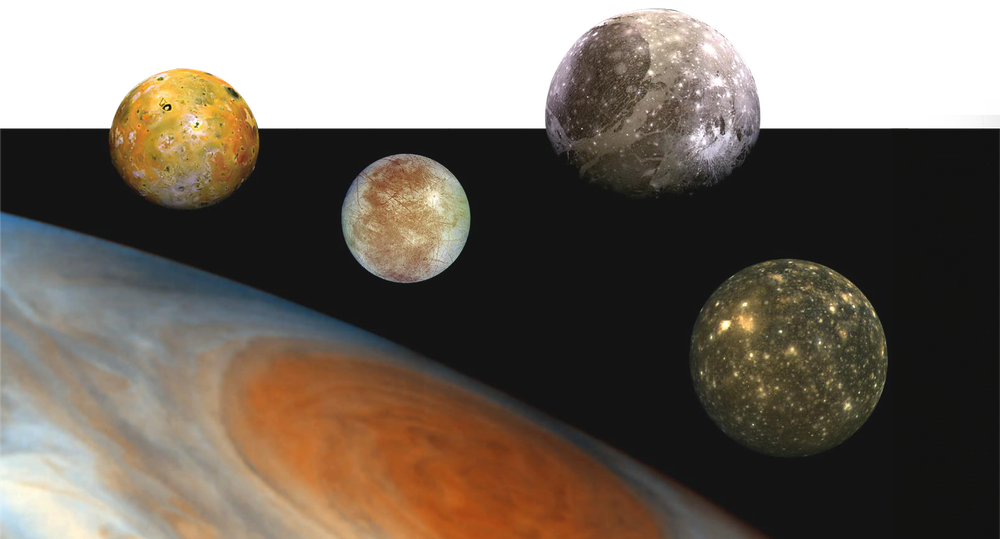

Yet at least one notable achievement remained for Marius – his observations of Jupiter's moons were more precise than Galileo's. And it was Simon Marius who followed Kepler's suggestion to avoid naming the four large moons of Jupiter 'Medicean moons' – as Galileo had proposed in honour of his patrons – or even 'Brandenburg moons', in honour of the Brandenburg-Ansbach princes. Instead, Marius gave them the names they still bear today: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, honouring some of the most illustrious companions in Greek mythology. But that is another story.

NASA/JPL/DLR

An article by Ulrich Köhler from the DLRmagazine 176