The Martian

DLR/ESA/FU Berlin

Only six people in the world have the privilege of naming surface features on Mars – and Daniela Tirsch is one of them. Now a planetary geologist at the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, she never dreamed of such a career as a child in Berlin – she wanted to be a dancer. The researcher tells us about her passion for the black dunes on Mars and explains why the most beautiful sand is on Earth – and why it is green. This interview is an excerpt from the German-language podcast 'DLR FORSCHtellungsgespräch'. It has been shortened and edited for the DLRmagazine.

In addition to images, audio recordings from Earth's neighbouring planet have been available for some years. In February 2021, for example, the Perseverance rover recorded the wind blowing across Mars. What goes through your mind when you hear something like that?

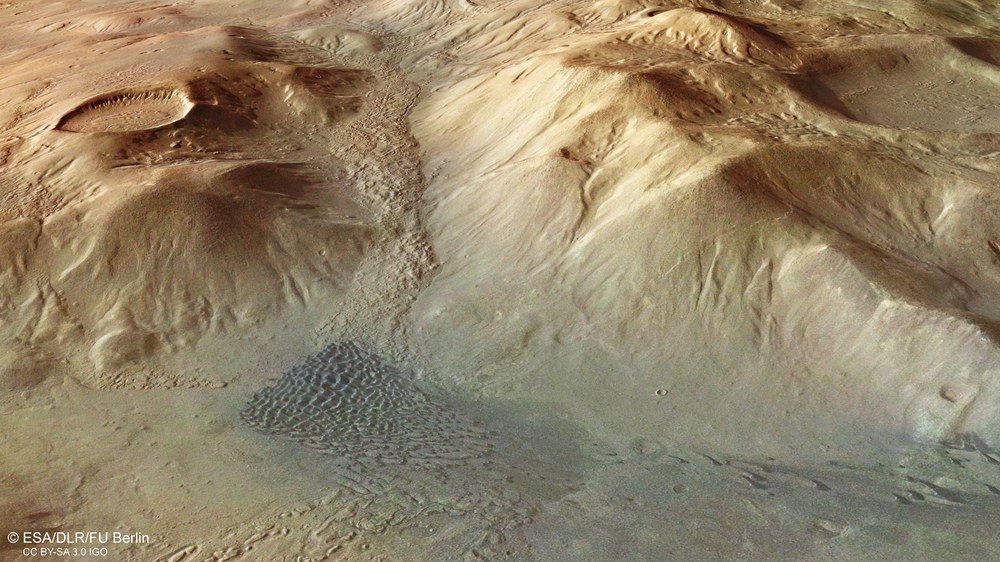

This sort of thing is very close to my heart – the dunes of Mars are my favourite topic and were the subject of my doctoral thesis. They are particularly beautiful and dark. Dunes are formed by the wind. I got goosebumps when I first heard the sound of that wind recorded on Mars itself. At the same time, I wondered why someone hadn't thought of sending a microphone to Mars sooner.

You've always had a soft spot for sand: you've been collecting sand from all over the world for many years. But what do you find so special about the dark dunes on Mars?

Most of them are found in impact craters. Some of the material was carried there by the wind, but it mainly originates from the dark layers exposed on the crater walls. The dunes look beautiful and consist of greyish-black volcanic material. If you want to study such dunes on Earth, you have to go to areas where volcanism and a relatively dry climate coincide. Some of these are very beautiful places – another great aspect of my research. For example, I have been lucky enough to go to Hawaii twice to study dunes in the Ka'ū-Desert, which are similar to those on Mars. That was amazing.

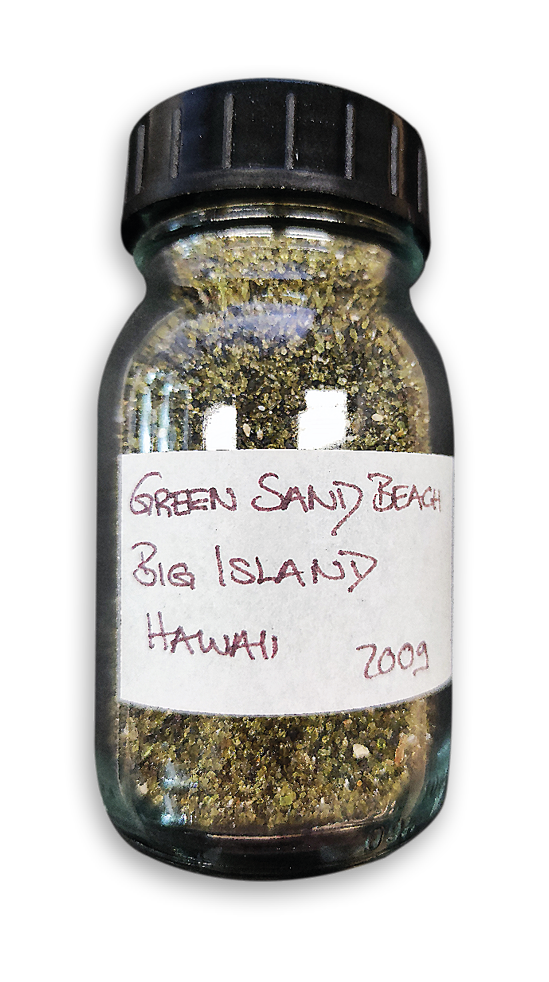

What is your favourite sample of sand, and why?

Oh, that is an easy question. It is from Hawaii, and I love it because the sand is green. It consists primarily of the volcanic mineral olivine. The sand is found at Green Sand Beach, a well-known place on the Big Island. This beach is quite difficult to get to. We walked through the heat for almost two hours and suffered many blisters. But then this cliff opened up before us, revealing a picture-perfect beach made of green sand. I had never seen anything like it before.

How did you become a planetary scientist? Planetary research was not originally on your wish list.

To be honest, I never dreamt of planetary research as a child. I actually wanted to be a dancer, but I had to give up on that dream for health reasons. So, I went to university and studied what was then my favourite subject at school – geography with a minor in geology and ecology. I loved it! During my job search, I came across a doctoral position at DLR. I was offered the job during the interview and thought: "So, now I am a planetary scientist!" On my first day at work, I was given a book about Mars… and that is how it all began.

Now you are involved in the Mars Express mission. The High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) instrument used on the mission was developed at DLR and regularly delivers images of the Red Planet.

Yes, I really enjoy this aspect of my work. HRSC allows us to create digital terrain models and images of the surface of Mars, so we can show Mars in colour and three dimensions. I think our images of Mars are very aesthetically pleasing, too.

You are also a member of an International Astronomical Union (IAU) working group on naming surface features on Mars. Have you been responsible for any particular names?

Well, I should start by saying that I'm extremely proud to be one of only six people in the world who get to name surface features on Mars. That said, we do not think up names, we just receive suggestions. I particularly like naming impact craters that are less than 50 kilometres in diameter. These are given the names of villages or smaller towns – those with a population under 100,000. Before I became part of the committee, I suggested naming a crater 'Jena'. At that time, though, Jena had an official population of 109,000 people, so my suggestion was rejected. So I proposed the name of my favourite village in Thailand – Pai. So now there is a crater on Mars called Pai. I still think that it is nice that you can bring Earth to Mars by immortalising the names there.

Thank you very much for such an interesting interview and a fascinating insight into the Red Planet.

The DLR Institute of Planetary Research

At the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin-Adlershof, scientists conduct research into the Solar System, particularly with regard to the origin, formation and development of planets, their moons and small planetary bodies such as asteroids and comets. Among other things, they are concerned with the question of whether life exists only on Earth or is also possible on other celestial bodies – such as extrasolar planets orbiting other stars. For this purpose, they develop cameras, spectrometers, laser altimeters and radiometers, which are used on missions to the planets, moons and small bodies found in the Solar System.

The DLR-FORSCHtellungsgespräch podcast is produced by Daniel Beckmann, Andreas Ellmerer and Antje Gersberg from DLR's Corporate Communications Department. This is an article from the DLRmagazine 173.