The story of the ISS

By the early 1980s, Europe had secured itself access to space. The Ariane launch rocket was proving a huge success and the Spacelab laboratory, developed and built in Germany, was ready to deploy on the US Space Shuttle. The members of the European Space Agency (ESA) had also demonstrated their mastery in constructing and operating research satellites. The Soviet Union had already demonstrated the logical next step: a permanently manned space station in Earth orbit. The idea of a European space station was debated in both Germany and France.

In the USA, space planners were having similar thoughts. However, the Americans initially chose to concentrate on developing the Space Shuttle, and the construction of a space station did not receive proper attention until the 1970s. This was by now the last area of space travel in which the USA had not yet caught up with or overtaken the USSR.

Race between East and West

On 19 April 1971 the Soviet Union launched its first orbital station Salyut 1 into space, a crucial step towards maintaining a permanent human presence in Earth orbit. The second generation of space stations was launched in 1977 in the shape of Salyut 6, which had a second docking ring for supply ships, enabling it to stay in space for much longer. Between 27 August and 3 September 1978, Sigmund Jähn became the first German cosmonaut to participate in the INTERKOSMOS partnership between the German Democratic Republic and the USSR. April 1982 saw the launch of Salyut 7, on which Frenchman Jean-Loup Chrétien spent two months and became the first Western astronaut to spend time on a Soviet space station.

In the Soviet Union, meanwhile, scientists were busy designing the third-generation space station which was successfully sent into orbit 300 kilometres above the Earth on 20 February 1986. This was the multi-modular space laboratory 'Mir', which had five research segments, later attached to the basic module, and a total mass of over 120 tonnes. Designed to last 12 years, it survived the collapse of the Eastern block and even gave Western scientists an opportunity to carry out long-term space research between the end of the Cold War and its controlled crash-landing in the Pacific on 23 March 2001.

The USA's next response was Skylab. Fitted in the third stage of Saturn V, the last Saturn rocket to be launched, in 1973 it gave three different three-man crews a total of 171 days in space to carry out scientific and technical experiments in solar and comet research, materials science, medicine, pharmacology, Earth observation, meteorology, biology and chemistry.

During the 1980s NASA was searching for ways to keep astronauts in orbit for longer. It was also looking for scientific experimental setups and commercial applications. In the growing political divide between East and West, brought to a head by nuclear armament, the construction of a space station by the Western nations was intended to be both a symbol of peaceful cooperation and a sign of the technological dominance of the 'free world'.

Plans for a joint international station

In 1983 the USA and its partners in Europe, Japan and Canada came around the table to discuss the possibility of a joint space station. In the summer of that year, MBB/ERNO and Aeritalia presented an initial industrial study, 'Columbus', by way of the European contribution. This study proposed a core station with a permanently docked module and a free-floating research laboratory attached to it.

On 25 January 1984, President Reagan tasked NASA with developing a permanently manned space station to be used for scientific and industrial research and the manufacture of metals and medicines. The launch was scheduled for 1992, the 500th anniversary of the rediscovery of America by Christopher Columbus.

Subsequently, it was Germany, Italy and France who coordinated the bold new venture in western European spaceflight. France concentrated on the further development of the launch vehicle, which culminated in Ariane 5, and the design of a manned European space plane called HERMES. Meanwhile, Germany and Italy concentrated on Columbus. Leading players in politics and industry hoped that this would give a strong stimulus to technology, involving as it did previously unknown demands in terms of reliability, precision and control of complex technical systems. Engineers and researchers eagerly awaited a significant leap in automation and robot technology, materials research, process and production technology, data processing and telecommunications.

1985: ESA decides on European participation in American station

In 1985 in Rome, the ESA Council of Ministers approved European participation in the American space station. The conditions of the European involvement were negotiated during subsequent transatlantic meetings. At the next ESA Council of Ministers in the Hague in 1987, ministers confirmed the Columbus programme and agreed on a further three-year preparation phase. At that time, the plan was still to launch Columbus using Ariane 5. The European contribution to the international space station was now to consist of a module permanently connected to the core station, an intermittently manned, free-flying laboratory, an unmanned polar research platform and a data relay satellite.

Plans for the space station were making progress - in the USA too. However, a number of factors led to delays in the schedule, one being complex annual budget negotiations in the US Congress. Another problem was the different visions of the nature of the space station: whether it should be a research laboratory or an orbital 'interchange' for future manned exploration missions. Above all, however, the loss of the Space Shuttle Challenger on 28 January 1986 set the programme back by several years. In 1987 the station was given its first name, one with political overtones: Freedom.

Freedom of research and understanding of peaceful use

There were many reasons why building an international space station was no easy task. It was, after all, a completely new form of international cooperation. The partner nations not only had to agree on a technological concept and how the station would be used, but also the legal framework. Who would own the intellectual property rights for new developments? How could experiments be carried out without infringing these rights? What civil and penal code would apply in a location not situated within any national territory? How would operating costs be covered and management of the station coordinated? In 1988, an international agreement was signed to resolve these issues. The agreement was described as an 'unprecedented contract' and is one of the largest documents relating to any international cooperation. Amongst its conditions, the agreement stipulated freedom of research and an understanding that the station would be used for peaceful purposes.

Cooperation instead of competition

Then, in 1989, the Berlin Wall came down - and soon after, Russia had a democratic constitution. Now that the Cold War between East and West was over, there was no need for a purely Western space station. Competition was replaced by a spirit of cooperation. In 1993, the USA invited Russia to join the international space station programme. In 1994, this move was approved by the other partners, who stood to gain from the Russian partnership: Russia had by far the greatest experience in space station design, construction and management. Russia also had highly experienced engineers with sensitive knowledge, for example in rocket technology, who might well have been tempted to emigrate to third countries such as Iran, Iraq or China - something which would not have been in the security interests of the West. Finally, having an extra partner on board would help redistribute the costs, for example through the provision of the Soyuz and Proton rockets. In the 1990s the partner nations also used the Russian space station Mir on several missions to train astronauts in joint tasks in space.

The cost of the new project had grown, as had the technical problems associated with HERMES, a programme which was cancelled in 1993. This, combined with the global economic crisis of the early 1990s and the accession of Russia to the International Space Station - now neutrally renamed 'Alpha' or 'ISS' - demanded a fundamental rethink. The Russians wanted to incorporate their developments for the originally planned Mir 2, which the country could scarcely have financed by its own efforts. With the HERMES programme cancelled, there was no means of maintaining the free-flying European laboratory, and this component was dropped. The docked European lab, which was subsequently given the name of the entire European programme Columbus, was also slimmed down as a result of new American plans. The polar platform, on the other hand, was removed from the European programme and used as a basis for the complex environmental satellite Envistat (launched in 2002). In 1995 in Toulouse, the ESA Council of Ministers integrated the European automated transfer vehicle (ATV), intended to transport payloads to the ISS, into the programme. When the ATVs start lifting off in 2007, the European partners should have covered their share of the running costs.

These modifications to the design concept and the new geopolitical situation in the 1990s caused further delays to the programme. Manned spaceflight lost strategic importance to European autonomy and became a field of international cooperation. The station became a powerful focus for East-West relations, a stabilising factor between the old superpowers and a means to defuse tensions.

1997: Agreement in principle between ESA and NASA

In 1997, ESA and NASA signed a principle agreement whereby Europe agreed to supply additional equipment, including two connecting nodes for station modules and laboratory equipment, to the USA. In return, Columbus was now to be launched using the Space Shuttle. A contract was signed with Russia for the duty-free entry and exit of goods relating to the ISS collaboration and for the supply of a European robot arm and data management system for the Russian segment of the ISS. ESA also reached an agreement with Japan on the exchange of hardware.

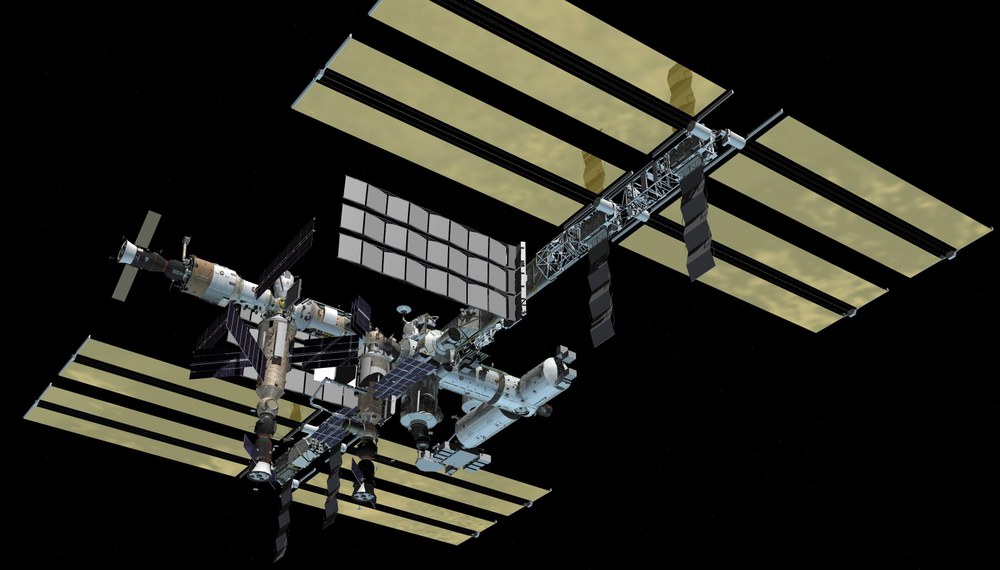

On 29 January 1998 the relevant ministers from the partner nations met in Washington to sign a new intergovernmental agreement giving the ISS a legal framework under international law. Compared with the 1988 agreement, the principle of equal partnership was more in evidence, although the leadership of the USA in design and construction was still an integral part. The station had undergone substantial changes since 1988. Once assembly was completed, its configuration was to consist of more than 100 components and it was to have an inner volume similar to that of a jumbo jet. This space was to be occupied by six research labs (two American, two Russian, one European and one Japanese) and four supply modules. Three robot arms would be available for extra-vehicular activity (EVA). The launch of the Russian module Zarya ('Dawn') from Baikonur on 20 November 1998 signalled the start of the most intensive period of flight in the history of space travel. The loss of the Space Shuttle Columbia on 1 February 2003 led to a further delay of over three years and a marked reduction in the number of planned shuttle flights until this launch system comes to a scheduled end in 2010. In February 2008 the european Columbus module was docked to the ISS.

7 February 2008: Columbus lifts off towards the ISS

The launch of the Space Shuttle Atlantis on 7 February 2008 not only marked the beginning of the mission of the two ESA astronauts Hans Schlegel from Germany and Léopold Eyharts from France. The launch also marked the beginning of the European space laboratory Columbus' ten-year mission on the ISS. It successfully docked with the Space Station and has been part of the ISS ever since.

The last Space Shuttle mission

In November 2010, the German government adopted the German Space Strategy, which stipulates the use of the ISS until at least 2020. From a technical point of view, up to six astronauts from the partner countries can work regularly in routine operations until then. In order to be able to guarantee a complete crew, ESA trained a new generation of European astronauts from 2009 onwards.

On 8 July 2011, the Space Shuttle 'Atlantis', which also brought the European space laboratory Columbus to the ISS, set off for the ISS for the last time. This 135th mission marked the end of an era.