Return to the Moon with Artemis I

Your consent to the storage of data ('cookies') is required for the playback of this video on Youtube.com. You can view and change your current data storage settings at any time under privacy.

It has been more than 50 years since astronauts last set foot on the Moon (Apollo 17, December 1972). That is set to change before the end of this decade with NASA's Artemis programme planning to once again land humans on Earth's natural satellite. This time, the mission will also include the first woman to travel to the Moon. But that is not all; a permanent base camp is to be established on the Moon in collaboration with international partners. Together with the Lunar Gateway, an orbiting space station that will serve both for research and as a 'transfer station' between spacecraft and the lunar surface, the next 'big step for humankind' is underway. This first crewed mission to Mars will be flown by both female and male astronauts.

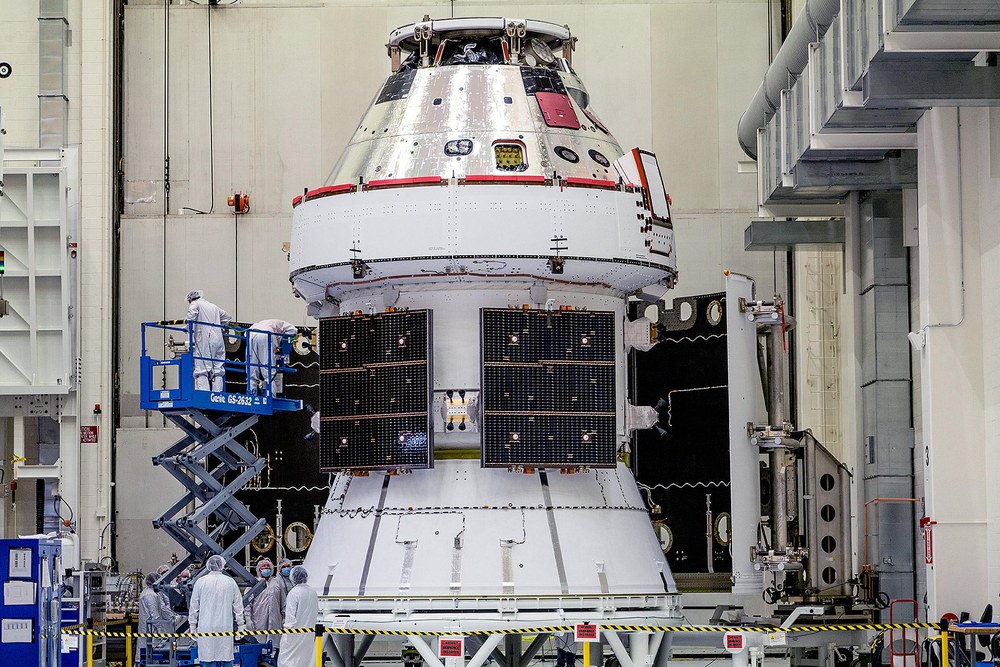

For this massive undertaking, NASA is developing a new rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS). It will be able to transport a spacecraft, astronauts and cargo to the Moon at the same time. The Orion spacecraft, which can carry a crew of four, has also been designed for missions to the Moon.

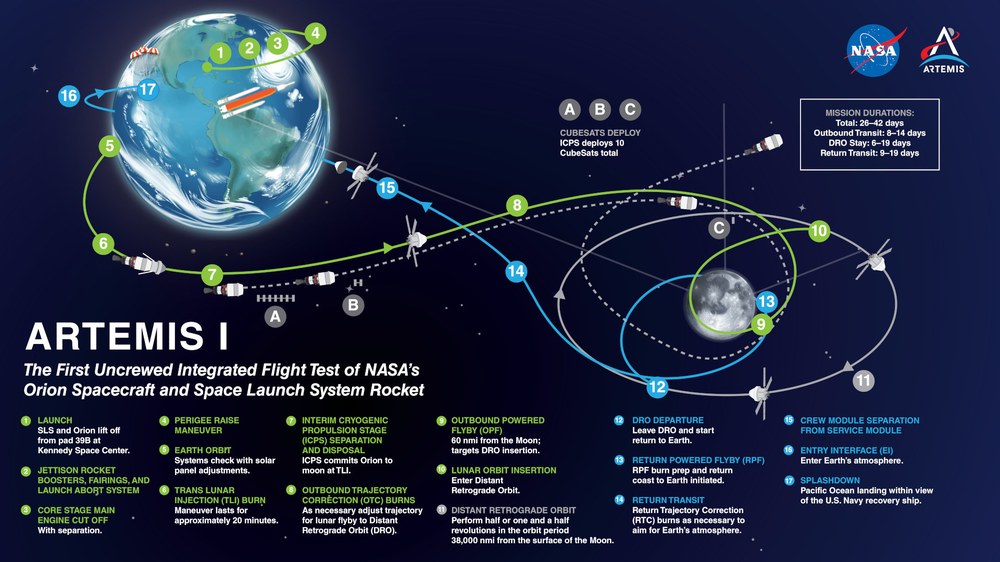

Artemis I is the first of a series of missions in NASA’s Artemis programme. On this uncrewed mission, all the newly developed systems were tested regarding the interaction between the Orion spacecraft, the Space Launch System (SLS) and the ground systems. Artemis II will carry a crew of four and orbit the Moon. Artemis III is set to land humans on the Moon again.

ESM – German technology propels missions to the Moon

A vital element of the Orion spacecraft is the European Service Module (ESM), which is being built to a large extent in Germany by the European Space Agency (ESA) on behalf of NASA. It contains the main engine and provides electricity using four solar sails. It also regulates the climate and temperature in the spacecraft and stores fuel, oxygen and water supplies for the crew. The Orion spacecraft, and with it the ESM, is considered a key milestone for future crewed exploration missions to the Moon, but also to Mars and beyond. The Artemis collaboration is the first time NASA has relied on partners from other nations for a critical component of astronautical missions – a tremendous vote of confidence in the capabilities of spacefaring nations in Europe. Under the industrial leadership of Airbus Defence and Space in Bremen, a European industrial consortium involving 10 countries has realised the first ESM-1 flight unit. Fittingly, ESM-1 bears the name of the Hanseatic city.

With Artemis, NASA is collaborating with international partners on a critical component of an astronautical mission for the first time. This is a significant vote of confidence in the performance of spacefaring European nations. A European industry consortium, led by Airbus in Bremen and spread across 10 countries, has now implemented the first ESM-1 flight unit. ESM-1 bears the name of the Hanseatic city from which it originates – 'Bremen'. To date, NASA has ordered six European service modules as part of its Artemis programme.

Germany is the primary European partner of the other spacefaring nations involved in the ISS (USA, Russia, Japan and Canada) and was a major supporter of the decision to build the ESM at the ESA Council at Ministerial Level in Naples in 2012. Germany provides approximately 50 percent of the ESM programme budget, with the country's share managed by the German Space Agency at DLR.

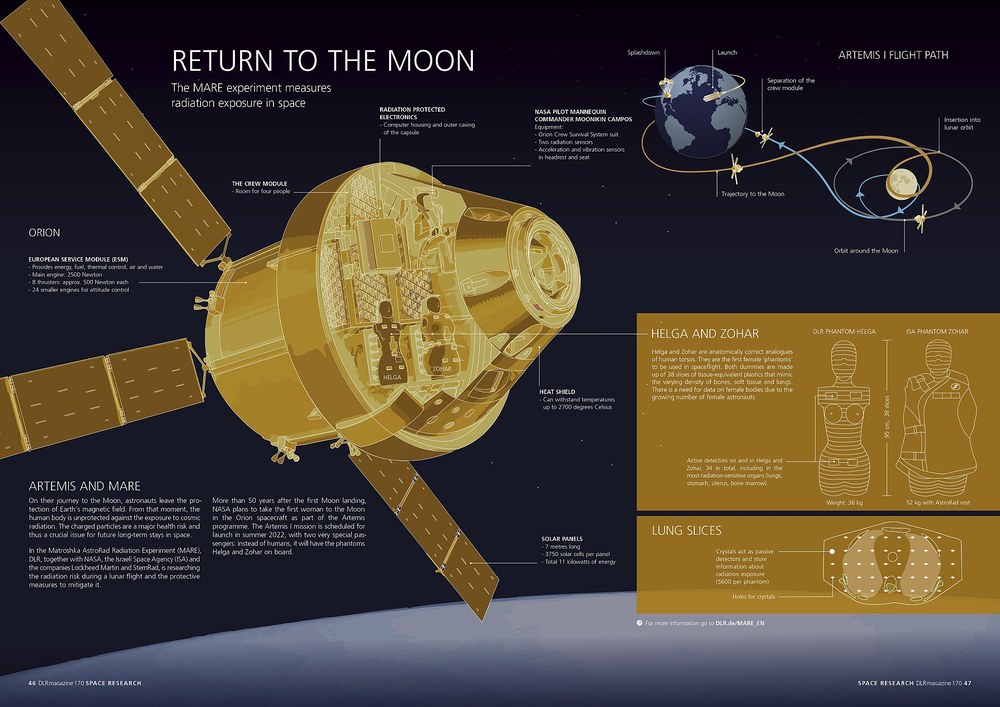

MARE – Radiation exposure on a journey to the Moon

The first Artemis mission took place without a flesh-and-blood crew. However, the flight to the Moon and back, which lasts a maximum of 42 days, was not entirely 'uncrewed'. Two female 'phantoms' were on board – Helga and Zohar. These research mannequins were equipped with special radiation detectors that replicate the female torso, including its reproductive organs, to enable measurements of the radiation dose received by organs that are particularly sensitive to radiation. The Matroshka AstroRad Radiation Experiment (MARE), led by the DLR Institute of Aerospace Medicine, was researching the radiation exposure of future Artemis crews.

MARE was also the first to measure the radiation exposure to the female body beyond the orbit of the International Space Station ISS. The female body is more sensitive to the effects of ionising radiation than the male body. It is therefore important to develop protective measures for the crews of future long-term missions based on this data. Zohar, contributed by the Israel Space Agency, flew to the Moon with a protective vest (AstroRad) made by the Israeli company StemRad, while Helga flew without any protection. In this way, the identical models collected comparable data sets. A total of more than 6000 passive measurement sensors were placed both on the surface of and inside the 'phantoms'. After the flight around the Moon, the radiation values measured by both models were compared in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the AstroRad protective vest.

For the first time, MARE also continuously collected measurement data that can be used to determine the radiation exposure inside the spacecraft at specific times during the flight to the Moon. This was achieved using, among other things, 16 radiation measuring instruments developed by DLR – the DLR M-42.

During the Artemis I mission, the Orion spacecraft travelled almost 500,000 kilometres from Earth – further than any crewed spacecraft has ever flown. These were the best conditions for collecting a lot of data with the help of the test mannequins, which will make similar journeys safe for future human crews.

Multimedia