From the car to the tram brake

Following the cessation of hostilities in World War I on 11 November 1918, the Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28 June 1919. It had far-reaching consequences for aviation within the German Reich. Until 1922, both aviation research and the construction of high-performance aeroplanes and aircraft engines were prohibited. Consequently, researchers sought alternative sources of income to finance their research facilities and personnel …

The ban on aeronautical research had a profound impact on the two key aviation research institutes in the German Reich – the Deutsche Versuchsanstalt für Luftfahrt (DVL) in Berlin-Adlershof and the Aerodynamische Versuchsanstalt (AVA) in Göttingen. While these establishments had previously centred their wind tunnel studies on airship models, aeroplanes and aircraft engines, the 1920s witnessed a diversification of objects under scrutiny within aeronautical research facilities.

Cars and rail vehicles

In 1921, Edmund Rumpler (1872–1940) subjected his 'Rumpler Raindrop Car' to testing in the AVA wind tunnel. Rumpler had been designing aircraft until the end of the First World War, after which he turned his attention to automobile construction. He knew that aerodynamic research could be transferred to ground-based vehicles. Similarly, companies such as Daimler acknowledged the value of methodical wind tunnel testing, submitting numerous racing car models for evaluation at the AVA during the 1920s and 1930s.

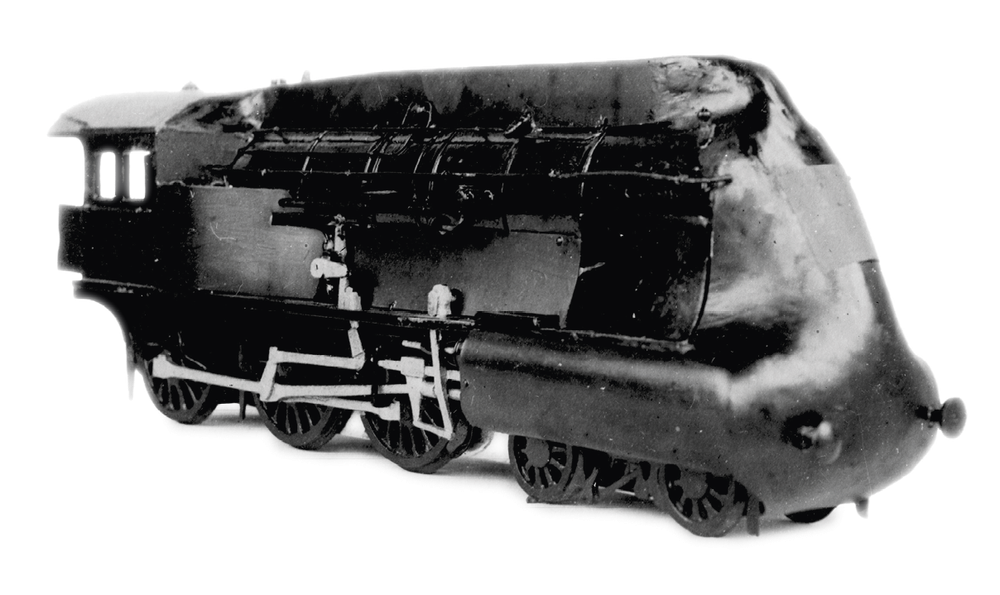

Another mode of transport that found its way into the AVA after the First World War was the rail vehicle. Around 1920, Albert Betz (1885–1968), AVA's deputy director, conducted comprehensive measurements on locomotives with and without deflectors to reduce drag, aiming to reduce train operational energy costs. This initial research was extended – commissioned by the Berliner Straßenbahn Betriebs-GmbH in 1928 – to encompass not just locomotives, but also their tenders and even brakes and sand spreaders for trams.

Wind turbines

Betz's research scope extended beyond rail vehicles to encompass wind turbines for power generation. Escalating coal prices in the German Reich due to the occupation of the Ruhr region by French and Belgian troops from 1923 to 1925 prompted a quest for alternative energy sources. Leveraging his expertise in propeller design, acquired before and during the First World War, Betz formulated an aerofoil theory for rotor blade design, documented in his 1926 publication, 'Windenergie und ihre Ausnutzung durch Windmühlen' (Wind Energy and its Utilisation by Windmills). His pioneering work on rotor blade design remains relevant today.

From vacuum cleaners to ski jumpers

The restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles were finally relaxed in 1925, allowing the resumption of research activities in civil aviation. Although this improved the financial situation of the AVA in the second half of the 1920s, after 1925 the research organisation was still heavily dependent on contracts from outside the field of aeronautical research. It was a stroke of luck for the AVA that the vacuum cleaner industry discovered wind tunnel research. Contrary to Loriot's famous sketch about the Heinzelmann vacuum cleaner ("The Heinzelmann sucks and blows where mum can only vacuum"), which was advertised as a promising combination appliance, the vacuum cleaner industry was not interested in developing new appliances, but merely in determining the air permeability of the dust bags. This was meticulously investigated by the AVA until the 1930s.

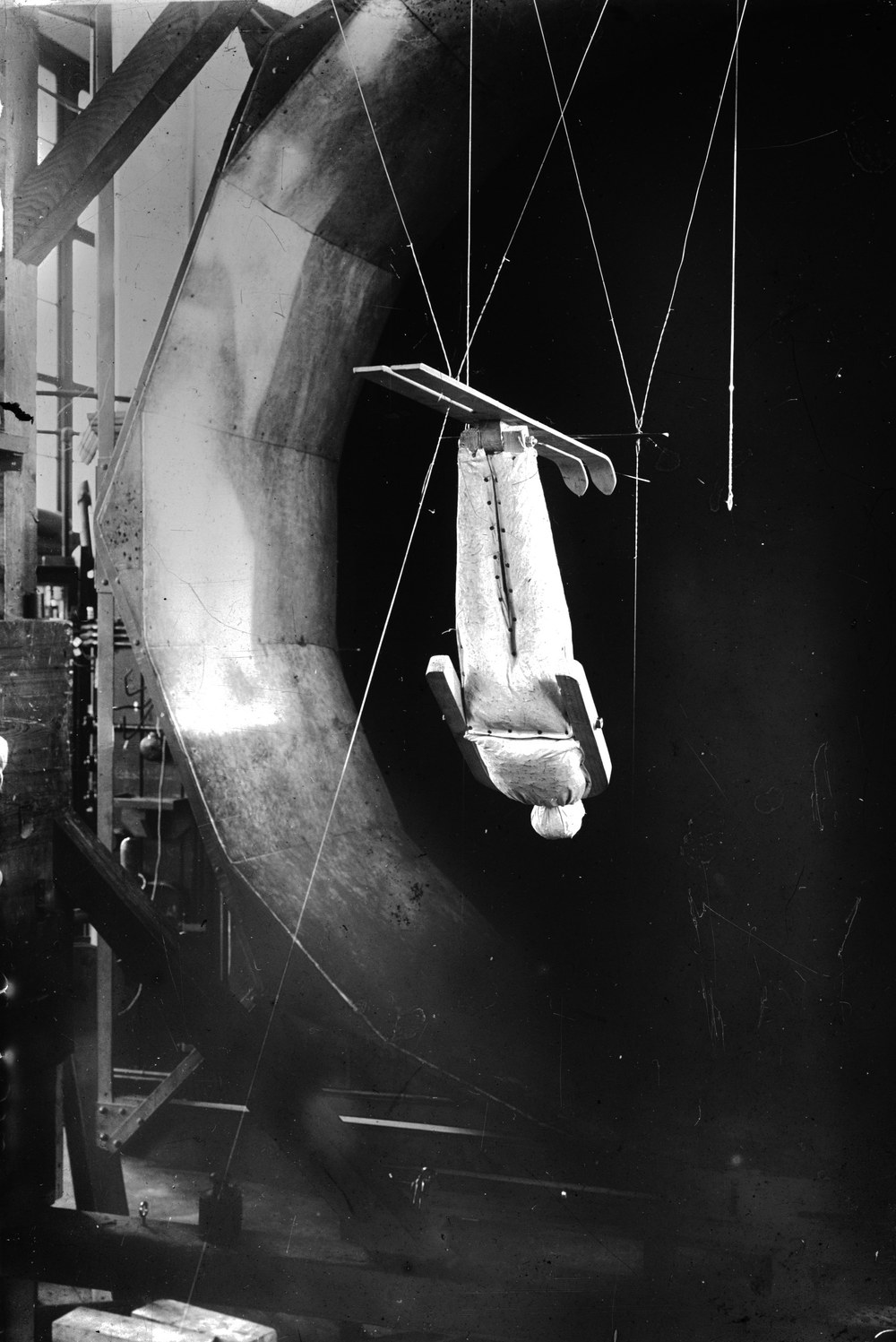

In 1927, the AVA received a rather unusual request from the Swiss Ski Federation. The association wanted to determine the optimum position of a ski jumper in flight and asked the AVA for help. The AVA constructed a manikin and analysed its performance in a wind tunnel. To this day, ski jumpers adopt the optimum body position determined in the AVA wind tunnel during their flight to achieve the longest possible jump. This is similar to a vertical wing profile.

Seeing restrictions as an opportunity

The restrictions imposed on the AVA in the field of aviation research by the Treaty of Versailles also provided an opportunity for the institute to expand its range of expertise. The treaty was therefore not only an obstacle for the AVA but also a catalyst from which the research institute benefited in the long term. Even after the Second World War, a number of unusual objects of study found their way to the Göttingen research centre. Find out what they were in the next issue of the DLRmagazine.

An article by Jessika Wichner from the DLRmagazine 174.