Come in, Gräfelfing

Ever heard of Gräfelfing? A train from Munich to Lake Starnberg will take you through the unassuming town, where making a stop is definitely worth your while. The rural idyll may appear much like any other, but everything changed here in 1908 when radio frequency technician Max Dieckmann (1882–1960) set up the Gräfelfing Wireless Telegraphic and Air Electricity Test Station (Drahtlostelegraphische und Luftelektrische Versuchsstation Gräfelfing; DVG).

Dieckmann, who in 1907 took up an assistant position in the department run by experimental physicist Hermann Ebert (1861–1913) at the Technical University of Munich, was involved in investigations into atmospheric electricity. A year later, he rented a meadowed area with a wooden hut in Gräfelfing for his students to use to carry out practical experiments. He called this newly acquired field the DVG. Soon, the first transmission masts sprouted, experiments began and the students were joined by the first official DVG staff.

Early tests on airships

In 1909, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (1838–1917) became aware of the DVG and asked Dieckmann to investigate whether radiotelegraphic transmitters could be used on airships. Initial experiments in Gräfelfing proved promising, so Dieckmann took the transmitters with him to Lake Constance – the home of the Count – to test them on board his airships. These tests were successful, and the Count gradually began to equip his airships with radiotelegraphic transmitters. In May 1912, for the first time in history, passengers on LZ 11 Viktoria Luise not only had the thrill of travelling on an airship, but were also able to send private telegrams to people on the ground during the flight. Whether the novelty of air travel or the possibility of communicating with acquaintances and relatives while en route was the greater attraction is hard to say. What is certain is that radio technology revolutionised aviation. It was now possible for airships and aeroplanes to communicate with each other and receive information from the ground. Now, nothing stood in the way of orderly air traffic control.

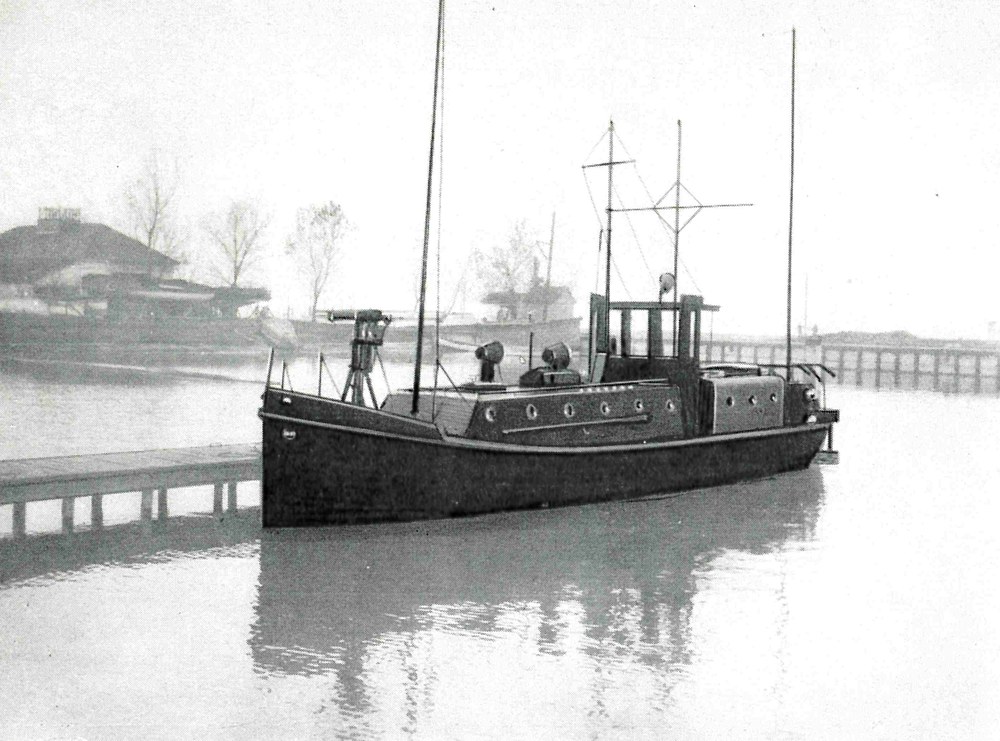

The development of the first aircraft autopilot functions at the DVG marked another major contribution to the modernisation of aviation. This development began on Lake Ammer. Before venturing into automatic flight control, Dieckmann had already developed a remote control system for motorboats. He intended the system to demonstrate the possibility of automating steering manoeuvres. In 1929, the DVG team demonstrated such a remote-controlled motorboat to the Hungarian Navy on Lake Balaton. Using a remote control and command transmission system, the team started the motorboat's engine, carried out various control manoeuvres, and even activated a machine gun to fire single shots and burst rounds. From then, it was only a matter of time before aeroplanes were equipped with autopilot functions.

The DVG was also involved in German radar development, with Lake Ammer once again playing a key role. The first radar device designed by the DVG was used to detect the Lake Ammer steamers ferrying tourists across the lake from a distance of one kilometre. The device also determined the speed of the steamers using the Doppler effect.

The birth of a famous tube

For those who find radio technology somewhat abstract, here is another outcome of the work carried out at the DVG. In this case, however, we have to travel a little further back in time, to around 1905. Back then, Max Dieckmann was working as an assistant to the physicist Ferdinand Braun (1850–1918), who taught in Strasbourg. In 1897, Braun had developed a cathode ray tube, which later also became known as the Braun tube. Dieckmann used this tube in 1906 to reproduce silhouettes in a format of three by three centimetres. He pursued this idea further in 1925, when he used a Braun tube to construct a device that can be found in almost every household today: the television. This was exhibited that same year at the German Transport Exhibition in Munich.

Radio research continued to grow in importance throughout the 1930s. The Oberpfaffenhofen Aeronautical Radio Research Institute (Flugfunk-Forschungsinstitut Oberpfaffenhofen; FFO) was founded in 1937, and Dieckmann was entrusted with its management. The DVG existed parallel to the FFO during this period. In 1942, the government of the German Reich bought the DVG from Dieckmann and incorporated it as a branch of the FFO. After the end of World War II, the FFO was initially closed, but was able to resume its work in 1954. After a short interim phase in Munich-Riem, it was transferred back to Oberpfaffenhofen in 1956.

Now, how about that trip to Gräfelfing?

An article by Jessika Wichner from the DLRmagazine 172