An extraordinary mission

The recent earthquakes in the border region between Turkey and Syria were among the worst natural disasters of the last century. Aerial images can help rescue workers get their bearings and assess the extent of local damage. Since 2016, DLR has been cooperating with the aid organisation International Search and Rescue (I.S.A.R.) Germany. Matthias Geßner and his colleague Jörg Brauchle, both from the DLR Institute of Optical Sensor Systems in Berlin, were on site in Turkey as part of this cooperation. Their most important piece of luggage: the MACS-Nano aerial camera system.

Matthias, in early February you both stood on a mountain in the city of Kırıkhan. Tell us about your experience.

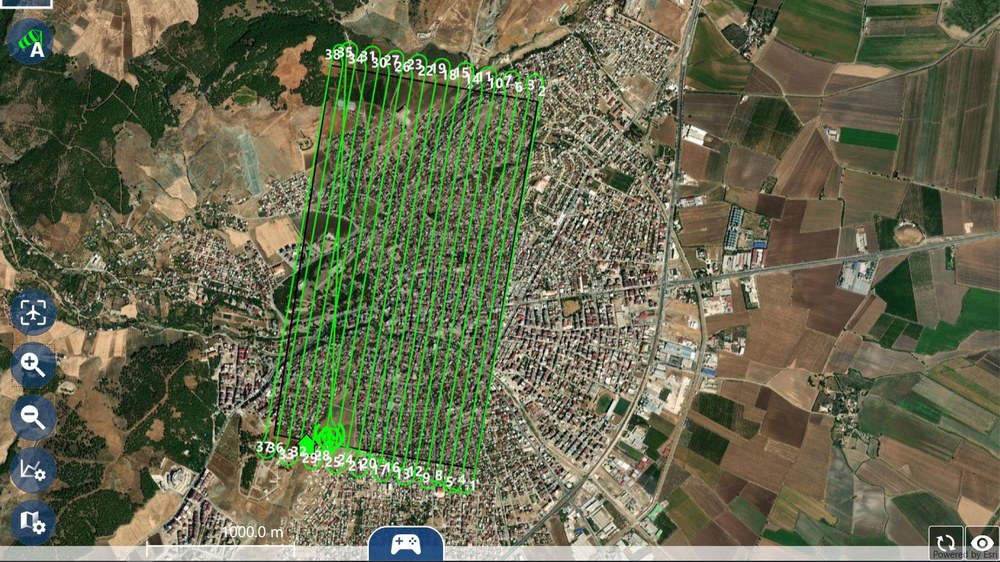

: That was a very emotional moment. The city that lay below us had been completely destroyed. People were living on the streets and we could see an incredible amount of suffering. We had been on site for three days and had already carried out some mapping flights with our Modular Aerial Camera System (MACS). However, after the first flight with the drone, it was clear that our system would not be enough to map the entire city in time. We usually use a larger drone system for precisely such purposes – but it was at the manufacturer Quantum Systems in Gilching for modifications at the time of the quakes. So, our DLR colleagues in Berlin and the manufacturer's team did everything they could to get the drone ready for use literally overnight. The support of the German Federal Agency for Technical Relief (THW) was also essential in order to secure a cargo slot on the first scheduled relief transport from Germany. With this support, a ready-to-use flight system was set up and equipped within a few hours – just in time for the early morning take-off of the transport aircraft flying to Turkey. It was a real team effort. After a 12-hour drive to the arrival airport – which was different from the one initially planned – we finally had the drone in our hands. We were able to fly our system for the first time the next day – from atop the mountain in Kırıkhan. The effort paid off: within an hour, we had mapped 3.5 square kilometres of the city with our camera – three times as much as we had managed in the previous flights. But that was not all: telecommunications were mostly idle, but thankfully, at that moment, we had a stable Internet connection. So, we were able to transmit our map data directly to the United Nations' (UN) operations command system.

You were part of the I.S.A.R. Germany team for this mission. In addition to flying the drones, what other tasks did you carry out?

: The members of I.S.A.R. specialise in different areas of operation: management, search, rescue and medical care. We went through various training sessions beforehand, which gave us additional skills to assist as part of the rescue team. On the day we arrived, when it was already too dark to fly the drone, we were able to accompany a team and help where needed.

So, you found yourselves amid the rubble immediately upon arrival. That cannot have been easy.

: Indeed. There were situations for which I was prepared during exercises, but which took on a completely different dimension when I was confronted with them in real life. Rescuing people from the rubble is sometimes extremely difficult and can take a very long time. Relief workers have to make very quick decisions about whether or not a rescue is possible. There were cases where people were rescued from the rubble but then died shortly after. Sometimes the relatives were standing right next to them. But we also experienced successful moments in which people were rescued alive. Seeing the professionalism and commitment of the I.S.A.R. team working in this disaster situation made a lasting impression on me.

How can aerial photography assist rescue operations?

: Aerial images made available as soon as possible are enormously helpful for the effective coordination of emergency responders on site. With them, teams can get their bearings: Where is the extent of the destruction greatest? Which roads are passable? What is the fastest way for teams to get to the scene? The MACS camera has extremely high resolution. We generated a photo-realistic aerial map using its images in real time, which could then be transmitted directly to the mobile devices of the I.S.A.R. team or the THW. Our department is in close contact with the International Search and Rescue Advisory Group (INSARAG) of the UN. As a result, we can also transmit our situational awareness images in real time to their operations command system, the INSARAG Coordination and Management System (ICMS). In doing so, we are providing all relief organisations involved with access to the same maps.

What did you take away from the mission?

: Such a mission can only be accomplished as a team. Jörg and I used the drones to take the photos on site. We were assisted by our colleagues in Berlin around the clock to ensure that together we achieved the best possible result. In four days, we took more than 15,000 aerial photos, which allowed us to identify details on the scale of two centimetres. With this mission, we were also able to demonstrate what this new technology is capable of. One of our next goals is to establish a system developed by DLR consisting of the MACS camera and the drone as a permanent element of mission support at I.S.A.R. Germany. From my point of view, this could substantially improve disaster response.

An article by Antje Gersberg and Julia Heil from the DLRmagazine 172