The first female 'astronauts' return from the Moon

NASA

NASA

+++ Update: On Sunday, 11 December 2022, the Orion capsule of the Artemis I lunar mission successfully landed in the Pacific Ocean at 18:40 CET with the two astronaut phantoms Helga and Zohar on board. +++

- MARE is the first experiment to measure the radiation exposure on the female body during a flight to the Moon and back.

- The European Service Module (ESM) successfully steered the Orion spacecraft around the Moon and back to Earth.

- The Orion landing capsule faces an endurance test during re-entry into Earth's atmosphere.

- The landing of Artemis I can be followed onNASA's live streamon 11 December from 17:00 CET.

- Focus: Spaceflight, exploration, Moon, cosmic radiation, international collaboration

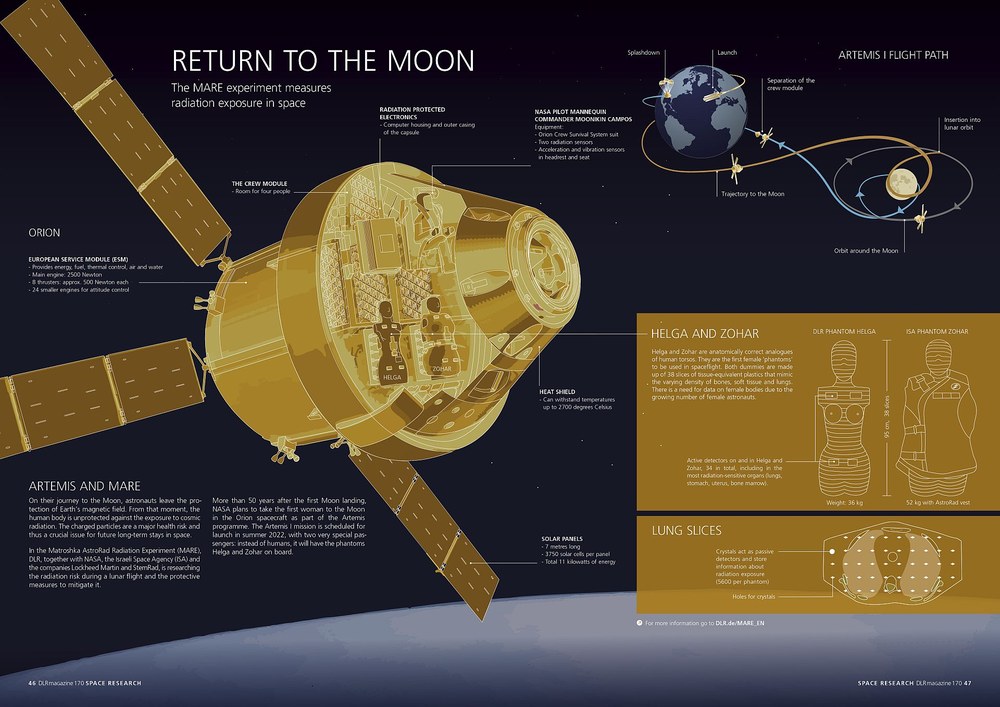

The return from the Moon is imminent. NASA's Artemis I mission is expected to splash down in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of California this Sunday, 11 December 2022 at 18:40 CET. The journey to the Moon, in lunar orbit and back to Earth lasted more than 25 days and now lies behind the Orion spacecraft, which is powered and supplied by the European Service Module (ESM). The two astronaut phantoms Helga and Zohar of the MARE experiment will return to Earth inside the Orion capsule. The #LunaTwins of the project, which is led by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR), measured cosmic radiation throughout the entire journey. Together with the NASA mannequin ‘Commander Moonikin Campos’ and the mascots Snoopy and Shaun the Sheep, they form the test crew of the first Artemis flight.

“Helga and Zohar have travelled a long way aboard the Orion spacecraft. On their far-flung lunar orbit, they were at times almost 400,000 kilometres from Earth,” says Thomas Berger, head of the MARE experiment at the DLR Institute of Aerospace Medicine. "In some cases, the trajectory took them to regions that no crew-worthy spacecraft had ever reached before. Now we are eagerly awaiting the return to Earth and the subsequent evaluation of the radiation measurement data."

Test run in lunar orbit

NASA

Since the launch of Artemis I on 16 November 2022, the Orion spacecraft has completed an extensive test run. The first close lunar flyby took place on the sixth day of flight (21 November), during which the Orion spacecraft approached the lunar surface to a distance of 128.7 kilometres. On 25 November, the spacecraft entered Distant Retrograde Orbit (DRO), which was to be tested with this flight. This orbit is very stable, which means that spacecraft do not have to perform orbit correction manoeuvres and therefore save fuel. Then, on 26 November, Orion broke the record set by Apollo 13 for the furthest distance from Earth travelled by a spacecraft designed for humans (400,171 kilometres) and reached its maximum distance from our home planet (434,522 kilometres) on 28 November. Another close flyby of the Moon took place on 5 December, also at an altitude of 128.7 kilometres. During this flyby, the moon's gravitational pull was used to help Orion on its way back to Earth.

Shortly before re-entry on 11 December, the crew module and the European Service Module ESM will separate. The crew module will return to Earth, while the service module burns up in the Earth's atmosphere during re-entry over the Pacific Ocean. The Artemis I trajectory has been designed to ensure any remaining parts do not pose a hazard to land, people, or shipping routes.

Re-entry at 40,000 kilometres per hour

The return to Earth is one of the most important tests on the Artemis I test mission. The heat shield of the new Orion capsule has not yet been tested under full load in real flight The capsule will hit the Earth's atmosphere at a speed of around 40,000 kilometres per hour when it returns from the Moon. The friction of the atmosphere will massively slow down the spacecraft. This "high-speed" re-entry is a real endurance test for the new capsule, whose heat shield will heat up to 2760 degrees Celsius. At just 523 kilometres per hour at an altitude of around eight kilometres, Orion's parachutes will then deploy and slow the capsule down further. Towards the end of the parachute descent, the Orion crew module will splash down in the Pacific Ocean near Guadalupe Island at just 23 kilometres per hour.

Passive and active radiation sensors

Helga and Zohar have been measuring radiation levels throughout their entire mission. The two measuring mannequins are modelled on the female body, including reproductive organs, in order to measure the radiation dose experienced by organs that are particularly sensitive to it. The female astronaut phantoms, each consisting of 38 slices, are 95 centimetres tall and weigh 36 kilograms. Zohar, provided by the Israeli Space Agency ISA, weighs 62 kilograms with an AstroRad radiation protection vest from the company StemRad. Inside two phantoms are organs and bones made of tissue-equivalent plastics that mimic the varying density of bones, soft tissue and lungs. More than 12,000 passive radiation detectors made of small crystals have been installed in these ‘organs’ and on the mannequins’ surfaces, as well as 16 active detectors from DLR in the body's most radiation-sensitive organs – including the lungs, stomach, uterus and bone marrow. By reading out the crystals, a three-dimensional image of the human body is created, revealing the total radiation exposure to different parts of the bones and organs during a flight to the Moon and back.

This treasure trove of data will be recovered with the Orion capsule after its landing in the Pacific Ocean. From its landing site off the coast of California, the still sealed Orion capsule will first be brought ashore by ship and then transported to NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. There, the capsule will be opened by the NASA team in the Multi-Payload Processing Facility (MPPF) building. “Once the capsule has been recovered, Helga and Zohar will be handed over to the MARE team. This is likely to take place in the second week of January 2023,” says Berger. “The data from the active measuring instruments will be read out on site so that we can quickly get a first impression of the radiation dose received during the mission.” The passive sensors will then be evaluated after the #LunaTwins have returned to the DLR Institute of Aerospace Medicine in Cologne, which is planned for the beginning of February 2023.

Forward to the Moon with Artemis

NASA

Artemis I is the first in a series of missions in NASA's Artemis programme. The programme envisions landing humans on Earth’s natural satellite again after more than 50 years, establishing a permanent base there together with international partners and building a space station in lunar orbit from which humans can set off for more distant destinations, such as Mars. Artemis I is the first step on this journey. This uncrewed mission will test all the newly developed systems and how they interact – the Orion spacecraft, the Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rocket and the ground systems. The safety of the astronauts is the top priority. This includes, in particular, protection against cosmic radiation, which is many times higher in space than on Earth – around 800 times higher on the Moon. In order to be able to take suitable protective measures for long-term missions in the future, we need to know the radiation exposure precisely. This is being researched as part of Artemis I with the MARE experiment.

The MARE experiment

The German Aerospace Center (DLR) is leading the MARE experiment. The main project partners are the Israeli Space Agency (ISA), the Israeli industrial partner StemRad, which developed the AstroRad protective waistcoat, as well as Lockheed Martin and NASA. MARE, in its complexity and in its international collaboration with numerous universities and research institutions from Europe, Japan and the USA, represents the largest experiment to determine radiation exposure for astronauts that has ever left low-Earth orbit. The measurements taken during Artemis I will provide valuable risk data for risk assessment and mitigation for future exploration missions and enable safe human exploration of space.