COUNTDOWN 37 (high resolution)

COUNTDOWN 37 (high resolution)

Some 20 years ago, on 2 November 2000, the hatch of the International Space Station (ISS) opened for the very first time, and the US astronaut William McMichael Shepherd and Russian cosmonauts Yuri Pavlovich Gidzenko and Sergei Konstantinovich Krikalev became the first ISS crew to move into their new home in space. Their 136-day stay came to an end on 19 March 2001 but marked the beginning of uninterrupted operations on board the space station. “These three pioneers made space history. This human outpost in space has been continuously occupied since Expedition 1. The ISS astronauts had come to stay,” recalls Volker Schmid, ISS Mission Manager at the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) Space Administration. “Expedition 1 was a major milestone for space exploration, not only for the USA, Russia and Europe, but also for space research in general. It paved the way for international cooperation and long-term missions,” says German ESA astronaut Matthias Maurer. Maurer is also hoping to fly to the ISS and thus become one of four German astronauts to have lived, worked and conducted research there.

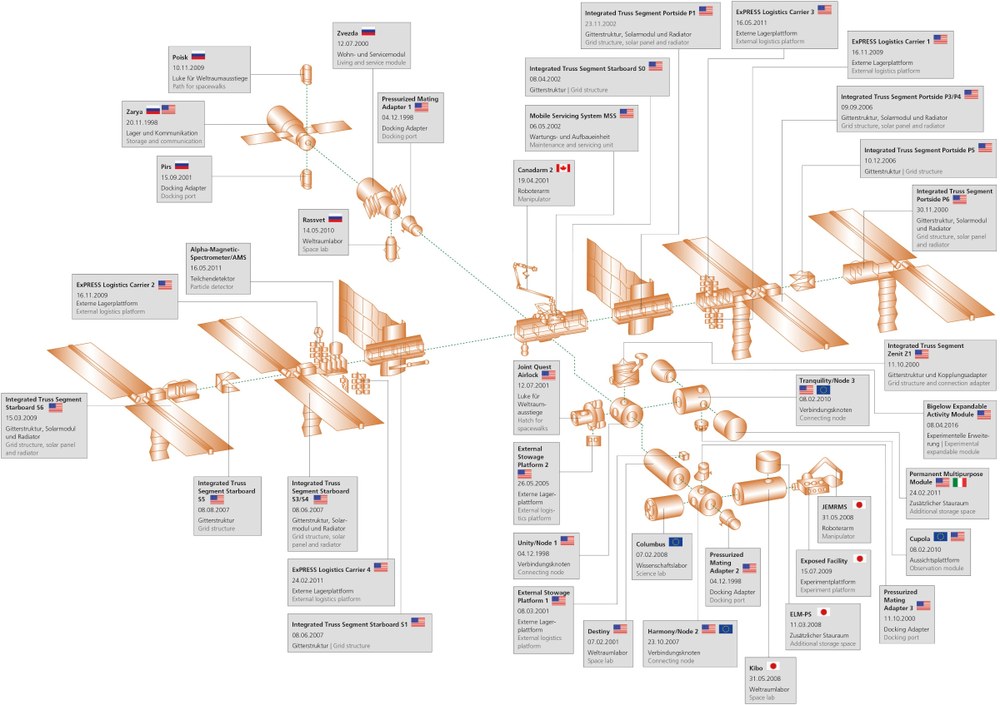

On 31 October 2000, Shepherd, Gidzenko and Krikalev began their journey in the Soyuz TM-31 capsule from an iconic site – Site 1 at Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, from which Yuri Gagarin had made the first journey into space 40 years previously. It was Shepherd’s fourth and final spaceflight, and the Expedition 1 commander was only the second US citizen to be permitted to fly in a Soyuz capsule. Gidzenko had previously spent 179 days in space as commander of the Russian space station, Mir. Krikalev was the first person to have visited the ISS twice, having previously travelled on board the US Space Shuttle Endeavour to join together the Russian ISS module Zarya (‘Dawn’) and US Unity modules in December 1998. That mission marked the start of construction work on the space station, which would span 10 years. In total, Krikalev spent 803 days in space – the third-longest of any space traveller.

There was plenty for Shepherd, Gidzenko and Krikalev to do during their four-month stay. “The Expedition 1 crew conducted pioneering work on the space station. They put essential support systems such as water treatment, a carbon dioxide absorber and the kitchen and toilet into operation,” says Schmid. The trio also installed computers for a US communications system, the controls for the Russian Zvezda module, the amateur radio system in the Zarya module for the Amateur Radio on the International Space Station (ARISS) project and manual controls and a monitor for the Telerobotically Operated Rendezvous Unit (TORU) system, which allows uncrewed spacecraft to be controlled from the station. “However, research on the ISS only began with the arrival of the three spacefarers. The very first experiment was the German-Russian PKE project to investigate the growth of plasma crystals in microgravity. Expedition 1 brought German science to the space station, and that research is still being conducted to this day,” says Schmid. “The first astronauts on board the ISS laid the foundations for the work that we are continuing now, 20 years later,” adds Maurer. “Today, of course, our experiments are much more sophisticated and advanced. We have learned a great deal along the way.”

Despite those early efforts, research on the ISS was very limited at the outset due to the lack of hardware and laboratories. “Back then, the ISS was still a rough diamond that needed to be steadily polished by the first crew,” continues Schmid. The three Space Shuttle crews that supplied Shepherd, Gidzenko and Krikalev during their time together in space brought crucial components such as the US solar arrays to the ISS, and even the US Destiny laboratory. “From that point onwards, things gathered momentum. Today, we have completely different opportunities on board the Space Station, such as studying cold atoms under microgravity conditions in the Cold Atoms Lab and looking into living cells in space for the first time with the FLUMIAS fluorescence microscope. CIMON, a crew assistant equipped with artificial intelligence is also now on board. The scope for research has expanded to a previously unimaginable degree,” says Schmid. Maurer adds: “The research possibilities have undergone incredible developments over the last 20 years. The experiments are much more sophisticated than they were back then. Now, the astronauts have a much better understanding of how this work should be performed in microgravity conditions, so the quality of the experiments is quite different. Nonetheless, those pioneers carried out first-class research and their experiments laid the foundations for the outstanding scientific research that is being conducted in space today.” A total of 2950 experiments have been conducted on the ISS to date. Around 390 of these stem from ESA utilisation programmes. German scientists have been involved in approximately 140 of these European experiments.

The European Columbus laboratory, which was manufactured in Bremen, was attached to the ISS on 11 February 2008. The presence of this laboratory, which constitutes essential infrastructure for permanent operation in low Earth orbit, allowed research capabilities in microgravity conditions to be radically expanded. “From that point, we had the message ‘Calling Munich’ being transmitted from Earth’s orbit to the Columbus Control Centre. Hearing those words over the radio for the first time was a very special moment, I must say,” recalls Felix Huber, Director of DLR Space Operations and Astronaut Training. For over 12 years, the Columbus Control Centre (Col-CC), located in the German Space Operations Center (GSOC) at DLR’s Oberpfaffenhofen site has been in constant contact with the control centres of the partner agencies (NASA, JAXA, RSA and CSA) and the astronauts on board the ISS. It monitors the module and its subsystems constantly in order to ensure that the astronauts have a safe and pleasant working environment. GSOC thus forms the interface between the Columbus experimental facilities on the ISS and the scientists in European user control centres.

In addition to science, the space station offers a number of opportunities for commercialisation. One current example is Bartolomeo, Europe’s first private external platform, built by Airbus in Bremen. Attached to the outer hull of Columbus, it has accommodated primarily commercial payloads since April 2020. Bartolomeo represents the dawn of a new era for the ISS. With the advent of commercialisation, Germany’s involvement with the ISS means direct benefits for the country’s economy. A cost-benefit analysis conducted by auditing firm PwC has shown that every euro invested has a return of one euro. In addition, the ISS is a driver of innovation for new industries and technologies, including laser communications, robotics and sensor systems.