BepiColombo spacecraft continues to 'fall' on its trajectory towards Mercury

Your consent to the storage of data ('cookies') is required for the playback of this video on Quickchannel.com. You can view and change your current data storage settings at any time under privacy.

MERTIS-Team

- In an unusual test, experiments designed for Mercury, with its lack of atmosphere, will be tested on the dense gas envelope of Venus.

- The MERTIS spectrometer (University of Münster and DLR) will acquire approximately 100,000 spectral images during two series of experiments.

- A second Venus flyby will take place in August 2021 – following this, BepiColombo will be on course for an orbit of Mercury.

- BepiColombo will arrive at the innermost planet in 2025, after another six Mercury flybys

- Focus: space, space science

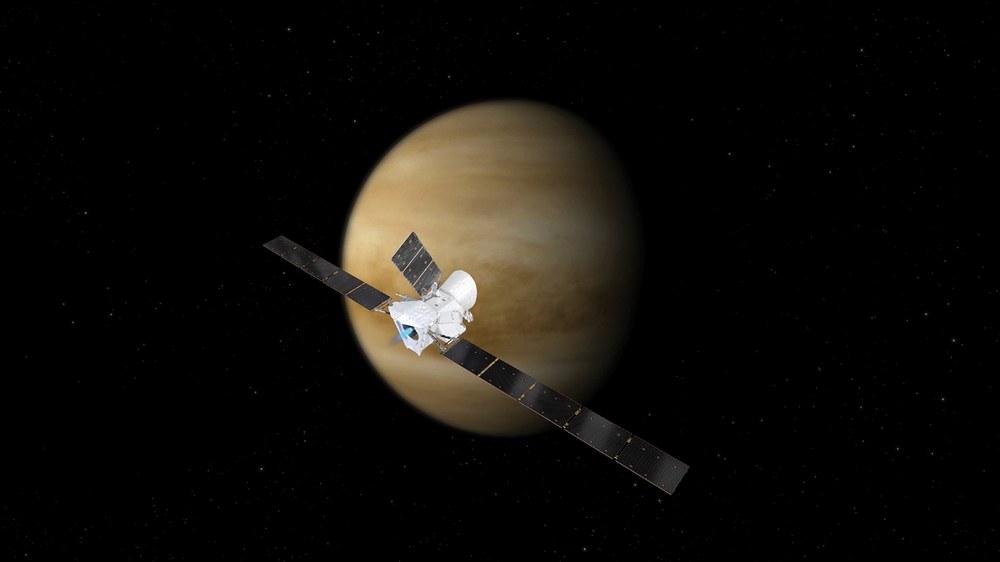

Approaching Venus from its day side, passing the planet, using its gravitational pull to slow down and continuing on its night side on course for Mercury: on Thursday 15 October 2020, at 05:58 CEST, ESA’s BepiColombo spacecraft will fly past Venus at a distance of approximately 10,720 kilometres and transfer some of its kinetic energy to our neighbouring planet in order to reduce its own speed. Two years post launch, the purpose of the manoeuvre is to lower BepiColombo’s orbit around the Sun towards the orbit of Mercury. The two orbiter spacecraft of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) are part of a joint mission that will reach this point after another flyby of Venus in August 2021. Following six close flybys of Mercury, the mission will then enter orbit around the innermost planet at the end of 2025. For planetary researchers and engineers at the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) and for the Institute of Planetology at the University of Münster, the Venus flyby is another opportunity to test BepiColombo’s MErcury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer (MERTIS).

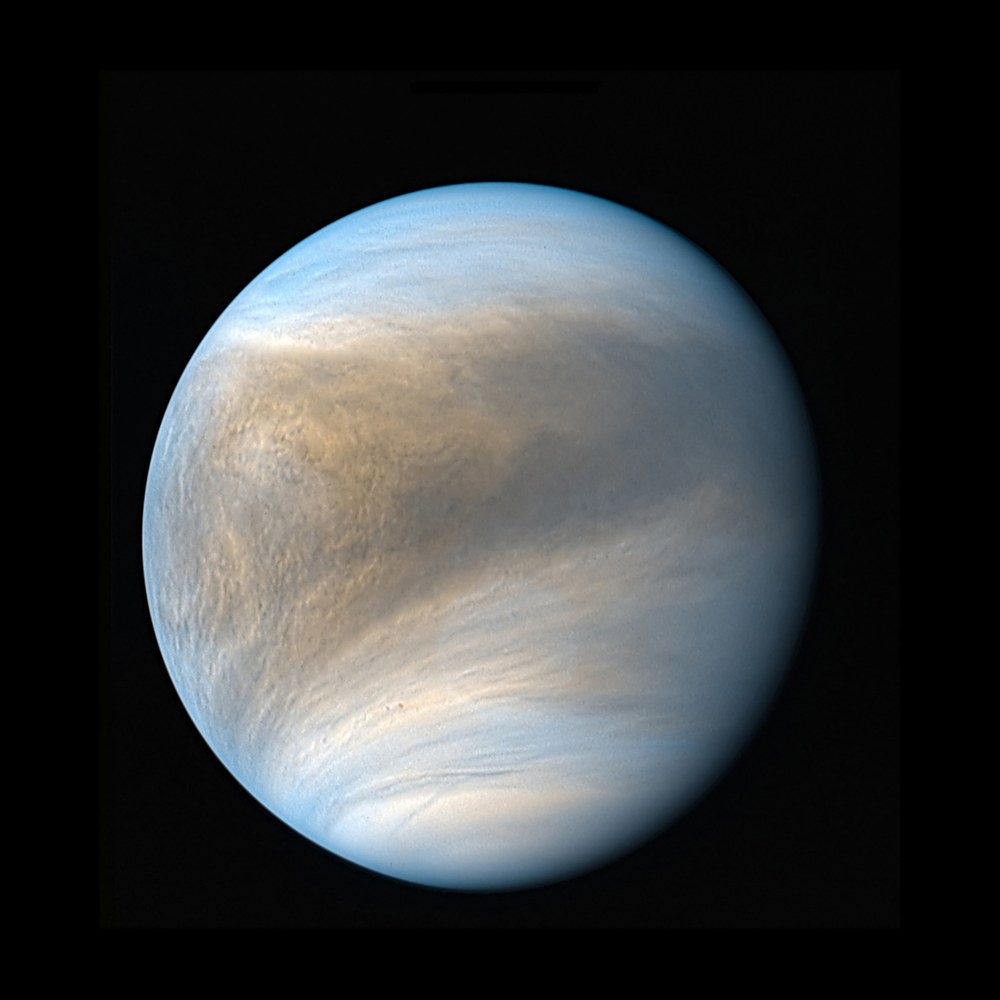

View of the Venus gas envelope with infrared sensors

The flyby of Venus and the Earth-Moon-flyby that took place in spring 2020 are spaceflight manoeuvres used to test the functionality of some of the experiments on board both orbiters, and to calibrate the sensors and signal chains with the data obtained. “Scientific measurements will also be carried out during approach and departure and at the closest approach to Venus,” say the two people primarily responsible for the MERTIS instrument, Jörn Helbert from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research and Harald Hiesinger from the Institute of Planetology at the University of Münster. “Our imaging spectrometer MERTIS, which we built together with industry and international partners, will be used again to make these measurements,” says Helbert. MERTIS was primarily developed to measure spectra of rock-forming minerals on Mercury’s atmosphere-free surface. But with its infrared sensors, it can also look into the dense gas envelope of Venus down to a certain depth. “We are already expecting some very interesting findings, with more to follow in 2021, when we will be much closer to Venus,” adds Hiesinger.

MERTIS is an imaging infrared spectrometer and radiometer with two uncooled radiation sensors that are sensitive to wavelengths of 7 to 14, and 7 to 40 micrometres, respectively. During two series of measurements, the first of which begins today, MERTIS will capture almost 100,000 individual images. The first series will begin as the spacecraft approaches from a distance of approximately 1.4 million kilometres from Venus up to a distance of 670,000 kilometres. After a pause to check the instrument, the second series will start at a distance of 300,000 kilometres, 11 hours before the Venus flyby, and will continue until BepiColombo is almost 120,000 kilometres from Venus four hours before the closest approach of the flyby.

Venus as the focus of planetary research

Venus is almost as large as Earth, but has developed in a completely different way. Its atmosphere is much denser, consisting almost entirely of carbon dioxide, and thus the planet experiences a very strong greenhouse effect. This results in a permanent surface temperature of around 470 degrees Celsius. There is no water and therefore it is thought that no life could survive on the surface. It is quite possible that volcanoes are still active on Venus. “These would be detected, for example, through the sulphur dioxide that they emit,” says Helbert. “Following the first measurements made in the 1960s and 1970s, about ten years ago, ESA's Venus Express mission recorded a massive reduction, by more than half, of sulphur dioxide concentrations. Venus literally 'smells' of active volcanoes! MERTIS could now provide us with new information." The experiments will be complemented by simultaneous observations from the Japanese Venusian orbiter, Akatsuki, and from a dozen professional telescopes as well as information from amateur astronomers on Earth.

Venus only recently came under the spotlight of science and the media when a group of astronomers used telescopes in Hawaii and Chile to prove beyond doubt the presence of the trace gas phosphine (or monophosphane, chemical formula PH3) on Venus. Phosphine is industrially manufactured on Earth for use in pest control, but is also produced by biological processes in sapropel or in the digestive tract of vertebrates. Phosphine is a very short-lived molecule, so there must be a current source of the molecule on Venus or in its atmosphere.

Previous modelling of natural phosphine sources such as volcanism, chemical reactions following meteorite impacts or lightning discharges have not been able to explain the measured concentrations. This is why the possibility that the phosphine is produced by microorganisms high up in Venus’s atmosphere is frequently debated by planetary researchers. This finding could suggest that life exists in the temperate ‘flying carpets’ of sulphuric acid clouds that exist at altitudes of 40 to 60 kilometres. The authors of the study themselves question this idea, however, and indicate the need for further measurements in the future. In the future, Venus will be the target of ESA and NASA missions.

Venus, an exoplanet on our doorstep

MERTIS and the other five activated instruments on board the Mercury Planetary Orbiter will not be able to detect any phosphine molecules from the distance of the flyby. Nevertheless, the flyby is scientifically interesting, as the spacecraft can be used to study Venus as if it were a distant, Earth-like extrasolar planet with a solid surface and dense atmosphere. “During the Earth flyby, we studied the Moon, characterising MERTIS in flight for the first time under real experimental conditions. We achieved good results," says Gisbert Peter, MERTIS project manager at the DLR Institute of Optical Sensor Systems, which was responsible for the design and construction of MERTIS. "Now we are pointing MERTIS towards a planet for the first time. This will allow us to make comparisons with measurements taken prior to the launch of BepiColombo, to optimise operation and data processing, and to gain experience for the design of future experiments." All experiments will focus on measuring the composition, structure and dynamics of the atmosphere of Venus, the ionosphere of the planet and – using the instruments on the Japanese MMO (Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter) – the induced magnetosphere of Venus.

Saving fuel with planetary flybys

Following BepiColombo's first flyby of Earth on 10 April 2020, its second flyby, this time of Venus is designed to continue to slow the spacecraft down without using any fuel. This is necessary in order to compress the spacecraft's orbital ellipse towards a circular orbit that is ultimately almost geometrically identical to the orbit of Mercury. The spacecraft 'falls' towards Venus on its spiralled orbit through the inner Solar System at various speeds depending on its distance from the Sun. At Venus, BepiColombo will reduce its heliocentric speed by 37 kilometres per second (133,500 km/h). The flyby will take place at a distance of 116 million kilometres from Earth. Venus is currently ahead of Earth in its orbit and is visible in the eastern sky just before dawn.

Due to the Sun’s strong gravitational pull, planetary missions to the inner Solar System can only be achieved with very complex trajectories. With the manoeuvre on Thursday, the spacecraft’s relative speed compared to Mercury will be reduced to 1.84 kilometres per second. At the end of its spiralled flight between the orbits of Earth and Mercury, BepiColombo will orbit the Sun at almost the same speed as Mercury. It will then easily be captured by the gravity of the smallest planet in the Solar System on 5 December 2025 and will manoeuvre itself into a polar orbit. BepiColombo was launched on 20 October 2018 on board an Ariane 5 launch vehicle from the European spaceport in Kourou.

The use of flyby manoeuvres was first implemented during NASA’s Mariner 10 mission, enabling the spacecraft to make two additional close flybys of Mercury after it had already travelled past the planet once. The calculations were made by Italian engineer and mathematician Giuseppe ‘Bepi’ Colombo, a professor at the University of Padua. Colombo was invited to a conference in preparation for the Mariner 10 mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, in 1970. After seeing the original mission plan, he realised that a highly precise first flyby could allow for two additional flybys of Mercury. The current European-Japanese Mercury mission was named in his honour.

Close European-Japanese cooperation

Overall management of the mission lies with ESA, which was also responsible for the development and construction of MPO. MMO was contributed by JAXA. The German contribution to BepiColombo is coordinated and mainly financed by the DLR Space Administration, with funds from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). The two instruments BELA and MERTIS, which were mainly developed by the DLR Institutes of Planetary Research and Optical Sensor Systems in Berlin-Adlershof, were largely financed from DLR's Research and Technology budget. The mission is also being supported by the Westfälische Wilhelms University of Münster, TU Braunschweig and the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Göttingen. A European industrial consortium led by Airbus Defence and Space designed and constructed the spacecraft.