Dawn falls silent – A successful mission comes to an end

- NASA's Dawn mission to explore the asteroid Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres – which it has orbited since 6 March 2015 – began on 27 September 2007

- Its fuel ran out on 31 October 2018, but the probe will keep orbiting the small planet Ceres in silence for decades to come

- Dawn was the first space probe to be placed in orbit around two different objects in the Solar System

- DLR contributed to the Framing Camera that maps the surface of the asteroid and which was indispensable for the spacecraft's navigation

- Focus: space, exploration

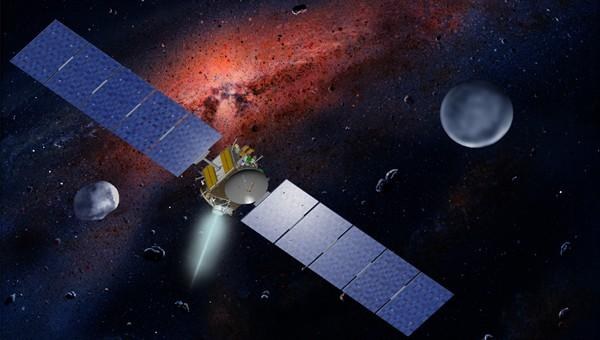

An extraordinary mission has drawn to an end, after the NASA space probe Dawn fell silent on 31 October. On 27 September 2007, Dawn set off to explore the asteroid Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres, which are located in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. On board was a German camera system that the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) helped to develop and build.

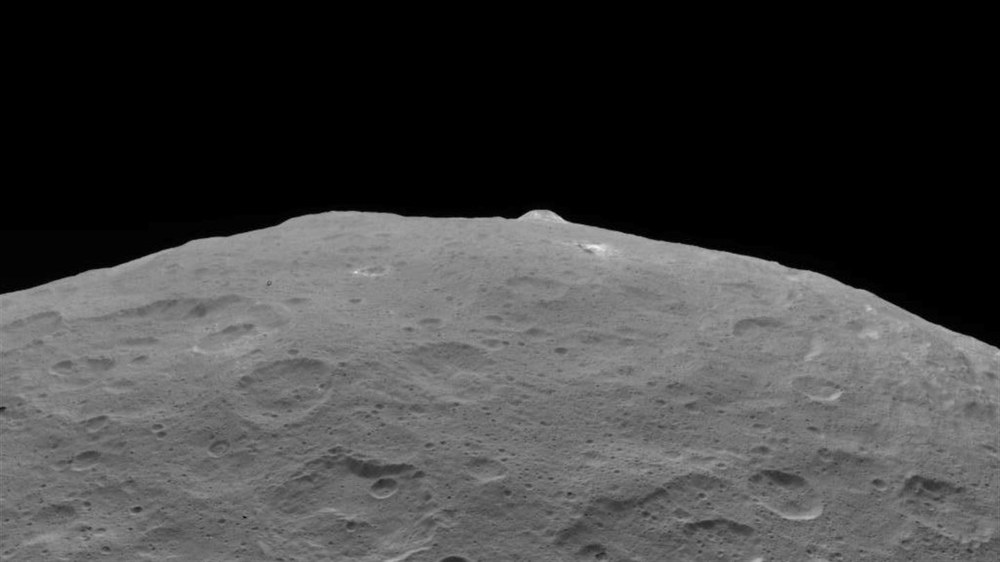

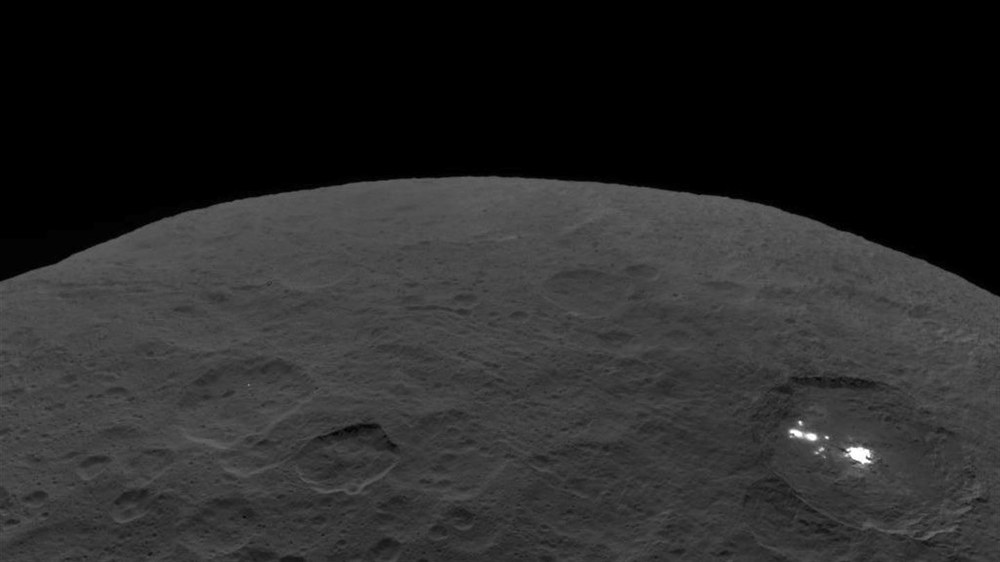

Since reaching the asteroid in 2015, the space probe has beamed back breathtaking images and fascinating information. The mission had already been extended several times, exceeding by far the expectations of the scientists researching the two planetary bodies, Ceres and Vesta.

"Dawn was the first mission to travel to two bodies in the Solar System and investigate them from orbit for a prolonged period. Insights acquired into Vesta and Ceres has resolved fundamental questions concerning the formation and evolution of planets. The Dawn mission has demonstrated how multifaceted our Solar System is and how far we are from researching and understanding it completely. It also became clear that the importance of water should not be underestimated, even on these small bodies," says Ralf Jaumann from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin.

Camera from Germany

The two Framing Cameras on board the space probe made a significant contribution, delivering spectacular and high-resolution images to map the two asteroids and to help the probe tonavigate. They were developed and built by the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in cooperation with the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin-Adlershof and the Institute of Computer and Network Engineering at the University of Braunschweig.

The spacecraft probably ran out of fuel, thereby losing the ability to navigate and communicate with Earth. Dawn did not respond to planned communications protocols with NASA's Deep Space Network on Wednesday, 31 October and Thursday, 1 November. As other reasons for the radio silence have been excluded, NASA assumes that the spacecraft – as expected – has used up the hydrazine fuel required to control or turn its solar panels and generate sufficient energy.

"Although we are sad that the Dawn mission has come to an end, we nevertheless celebrate its important accomplishments and insights, which will be of benefit to science as a whole," said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate in Washington. "The incredible images and data that Dawn collected from Vesta and Ceres – the two largest bodies in the asteroid belt – are crucial to understanding the history and development of the Solar System." Dawn set off to visit the two largest objects in the asteroid belt 11 years ago. It is currently orbiting the dwarf planet Ceres. Dawn embarked on its 6.9-billion-kilometre voyage in 2007. Equipped with an ion propulsion system, the spacecraft reached the largest objects in the asteroid belt in 2011. After an intense study of Vesta, which the probe orbited until 2012, Dawn continued on to Ceres, a dwarf planet with a diameter of 950 kilometres, making it the largest asteroid in the inner Solar System.

The data that Dawn sent to Earth allowed scientists to compare two worlds inhabiting the asteroid belt that have developed differently, delivering valuable insight into the formation of planets in the early Solar System. “We asked Dawn to fulfil incredible requirements, but the spacecraft rose to the challenge each time. It is hard to say goodbye to this astonishing orbiter, but the time has come,” said mission director and chief engineer Marc Rayman from the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Although radio contact with Dawn has broken off, the data delivered over the last 10 years will keep the scientific community busy.

Following the strict international planetary protection guidelines, Dawn will remain in 'quarantine' for at least 20 years, orbiting Ceres in silence before crashing to its surface as planned. Researchers apply this procedure to ensure that terrestrial microbes that may be adhering to the spacecraft do not contaminate the surface of Ceres, which might otherwise generate false conclusions in future research. Nevertheless, the experts are convinced that the spacecraft will continue to orbit Ceres for at least 50 years.

The mission

The Dawn mission is managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, which is a division of the California Institute of Technology. The University of California, Los Angeles, is responsible for overall Dawn mission science. The Framing Camera system on the spacecraft was developed and built under the leadership of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, Germany, in collaboration with the DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin and the Institute of Computer and Communication Network Engineering in Braunschweig. The Framing Camera project is funded by the Max Planck Society, DLR, and NASA/JPL.