Rosetta, Philae and comet fever

DLR opens the Rosetta mission exhibition at the Berlin Museum of Natural History

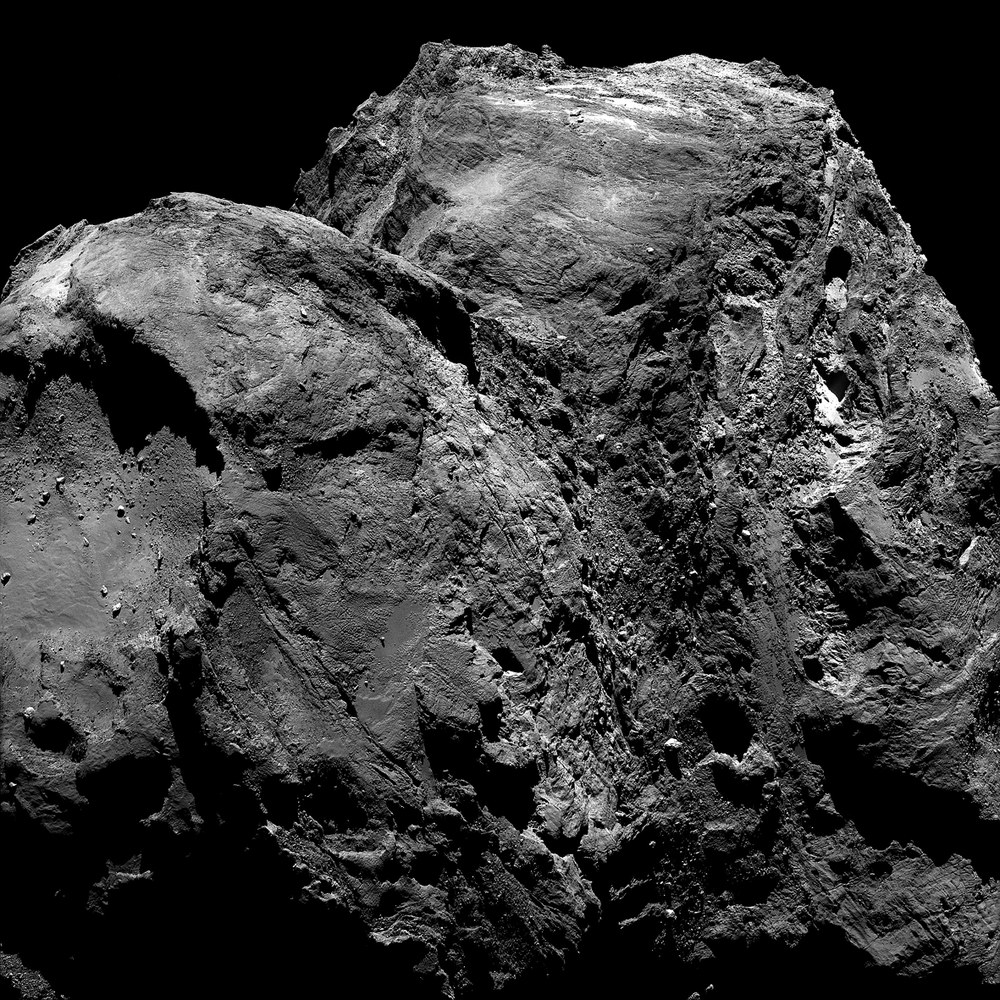

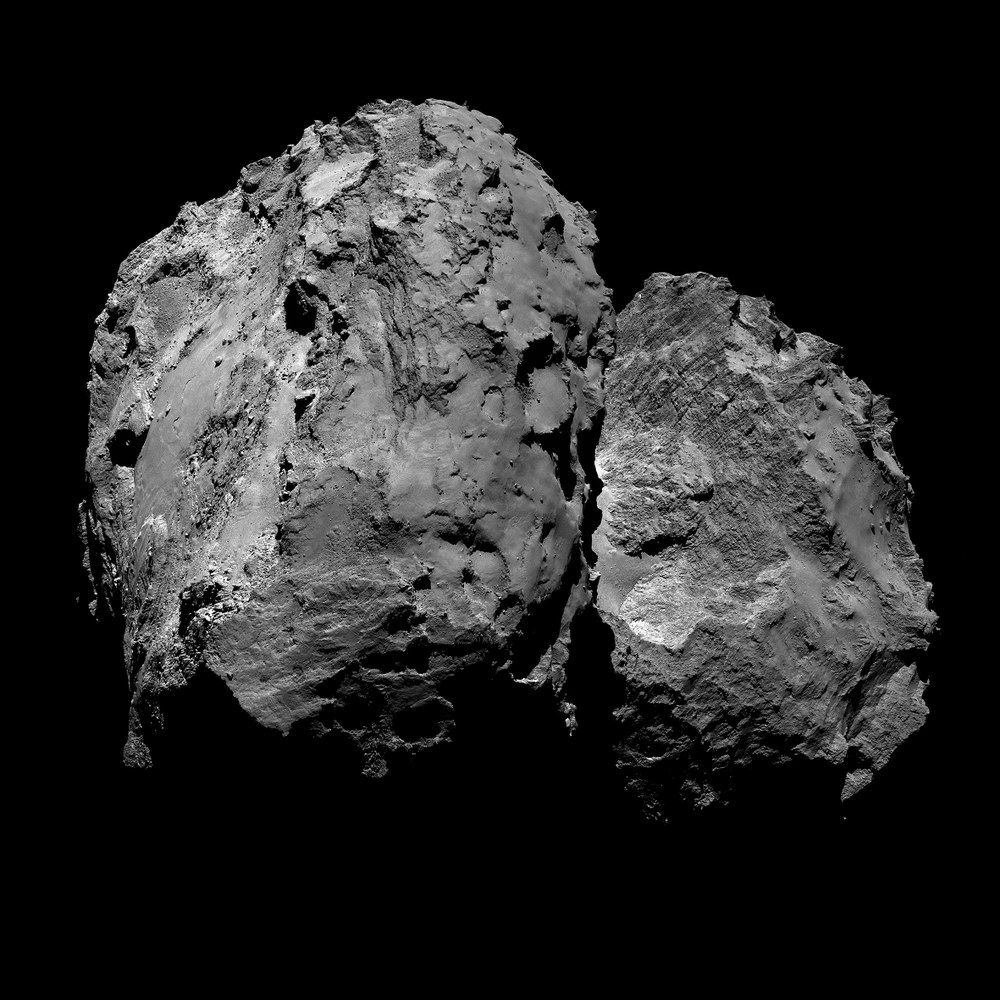

It's hard to say what surprised scientists and engineers the most during the Rosetta mission: the unusual form of Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko that earned it the nickname 'Rubber Duck'? The bizarre, unexpectedly varied landscape with fissures, terraces, crevasses, steep cliffs and even dune-like structures? The landing in November 2014, during which Philae bounced and flew for kilometres, touching down on multiple occasions instead of just once, before finally coming to rest? Perhaps the hard surface of the comet, although many had voiced initial fears that it might be too soft? The plethora of molecules discovered for the first time on a comet? All around the globe, people were rooting for the scientists as they for the first time, explored the surface of a comet on site, which was several hundred million kilometres away from Earth. Starting on 9 August 2016, the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR), in cooperation with the Berlin Museum of Natural History and the Max Planck Society, present the special exhibition ‘Comets: The Rosetta Mission – A journey to the origins of the Solar System’ that will showcase what makes comets so endlessly fascinating and how the Rosetta mission investigated their mysteries.

An ambitious mission with soaring targets

The idea to dispatch an orbiter and a lander to a comet was born almost 30 years ago. Observers became dissatisfied with merely casting a brief glance at these celestial bodies from the eatilmrliest days of the Solar System as they blazed across the skies. Instead, they wanted to stay on the surface for a while and observe the comet becoming increasingly active as it drew closer to the Sun, spewing dust and gas into space. “These processes, typical of comets, were insufficiently researched. There was plenty we had not grasped yet,” says Ekkehard Kührt, planetary researcher at DLR and the man responsible for DLR’s scientific contribution to the Rosetta and Philae mission. “We must not forget that comets are considered contemporary witnesses to the birth of our planetary system, as they have largely preserved their original properties. We want to use this fact to cast our eyes deep into this nascent phase.”

So the goals – and also the list of firsts that the European Space Agency (ESA) would have to perform as part of this mission – were largely defined: the first was to send an orbiter to orbit the comet and accompany it on its journey through space; then came the unprecedented feat of dispatching the landing craft Philae, developed by a consortium under the leadership of DLR, to touch down on the surface of the comet, where it would conduct on site measurements. This would be the closest one could ever get to a comet. It did not take long to come up with suitable names for the orbiter and the landing craft: Rosetta gave a nod to the Rosetta Stone, used to decipher the hieroglyphics. And in 1822, Jean Françoise Champollion used the inscriptions on an obelisk from the Temple of Philae to translate what until then had been entirely indecipherable hieroglyphics.

Together, Rosetta and Philae carried a total of 21 instruments to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko: among other things, the international teams of scientists wanted to photograph, drill, sniff, hammer and listen in the hope of finding out what the comet is made of, which physical properties it possesses and whether comets once brought water and building blocks for early life to Earth. "The emergence of life is a fundamental part of our research," explains Tilman Spohn, Director of the DLR Institute of Planetary Research. "Rosetta showed us that, while comets may conceivably have brought prebiotic molecules, they most certainly were not the main source of water on Earth."

A comet in the heart of Berlin

The international mission was launched on 2 March 2004. The journey through space, during which the Rosetta orbiter gained momentum by close Earth and Mars flybys, took 10 years. On its journey, the spacecraft photographed the asteroids Šteins and Lutetia before finally starting its approach toward Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko after two-and-a-half years of hibernation. Rosetta reached its destination on 6 August 2014, and Philae completed the hitherto unprecedented landing on a comet on 12 November 2014. The exhibition documents all of these stages and also includes a 1:5 scale model of the Rosetta orbiter, as well as a life-size replica of the Philae lander. Another protagonist of the mission, Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, stands over a street map of Berlin-Mitte in a scale of 1:1000 measuring 4.3 by 3.6 metres.

The ups and downs of visiting a comet

"The Rosetta mission and Philae's landing were and are unique," says DLR scientist Stephan Ulamec, who led the team responsible for Philae. The engineers and scientists working on Philae experienced their fair share of ups and downs: initially, the landing craft deviated from its plan and bounced on the surface. All the same, it spent 64 hours collecting data for its 10 on-board experiments while the team at the DLR Lander Control Center (LCC) worked round-the-clock in two-shift cycles to send commands to Philae and operate it. The lander reported back from its hibernation once more on 13 June 2015, sending more data packages and making contact with the team on the ground on seven more occasions.

The scientists received the last sign of life from their landing craft on 9 July 2015. The lines of communication then went dead, and Philae has remained silent ever since. With its eye still focused on the comet, the work of the Rosetta orbiter was far from over: the mission was so successful that it was extended by the European Space Agency for a further nine months, until 30 September 2016.

The insights gained during the mission are revolutionary: astounding images of a jagged, jet black comet outgassing increasingly as it approaches the Sun and hurling colossal streams of gas and cometary material out into space; the knowledge that comets are not ‘dirty snowballs’ consisting of loose material, but are instead icy, porous spheres of dust with an unexpectedly hard surface; and the realisation that comets like 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko did not actually bring water to Earth.

The Rosetta orbiter and the Philae lander will be united once more in September 2016: Rosetta will be landed on the comet’s surface, conduct a number of spectacular measurements, and finally join Philae and 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on their journey around the Sun. From then on, it will no longer be possible to make radio contact with either spacecraft.

The exhibition

'Comets: The Rosetta Mission – A journey to the origins of the Solar System', the DLR exhibition in cooperation with the Berlin Museum of Natural History and the Max Planck Society will open on 9 August 2016. Visitors are invited to attend a free pre-opening from 18:00 to 21:00 on 8 August 2016.