40 years of DLR energy research: 'The pace of renewable energies surprised us all'

Forty years ago, prompted by the shocking rise in oil prices at the start of the 1970s, political and economic figures began to think about an energy supply other than oil, coal, and uranium. The German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR), which at that time was still the DVLR, had already begun applying its expertise to energy research in 1969 to directly tackle this social challenge. In 1976 energy research was established as a secure, long-term research field at DLR. Research since then has been devoted to solar power plants, fuel cells, environmentally friendly gas turbines, energy storage systems, and wind turbines. The systems analysis studies in particular made key contributions to a pioneering energy policy in Germany that has also provided food for thought internationally.

To mark the 40th anniversary, we will present the highlights of recent years' energy research, allowing key players to communicate their work and outlooks for the future, to demonstrate how research can contribute to a sustainable and secure energy supply.

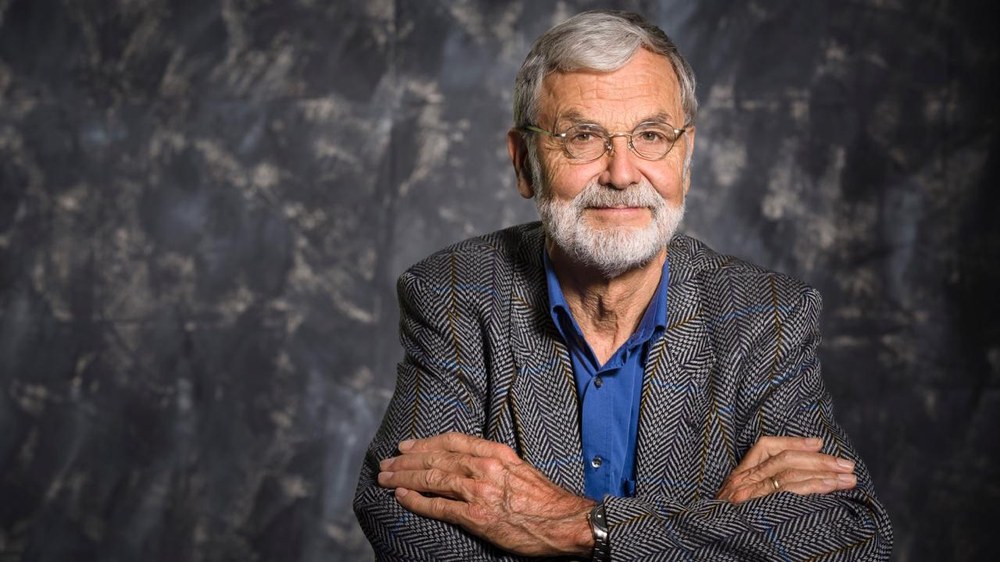

Joachim Nitsch started as an engineer specialising in aviation and aerospace technology. When DLR broadened its work to include energy supply research in 1976, he joined the initiative. In the first analyses of energy systems, he investigated the different forms of safe and environmentally friendly energy that could supply Germany in the future. Nitsch made a name for himself with his renewable energy scenarios for Germany, and these became the cornerstone for the country's energy turnaround. He looks back at 40 years of energy research at DLR in an interview with science journalist Tim Schröder.

Mr. Nitsch, you have spent your entire professional life at DLR, and were able to follow DLR as it went from being an institution for aeronautics and aviation research into one which today also conducts energy research on a sizeable scale.

Yes, and it was not at all expected at first. Following the oil crisis in 1973, the German Federal Minister of Research at the time, Hans Matthöfer, initiated a large study programme in which all sources of energy were to be scanned to find out to what extent they could contribute to Germany's energy supply in the future. The term 'renewable' or 'regenerative' energy did not even exist at that time. We spoke of 'non-fossil' and 'non-nuclear' energies. What it was actually supposed to mean was rather vague back them.

Then why, of all the institutions, did DLR, or its predecessor, the DFVLR, get involved in these 'nebulous' technologies?

To be honest, at first no one really wanted to have non-fossil and non-nuclear energies. The major German research institutions at that time were organised in a consortium, the AGF. The centres in Jülich and Karlsruhe were big in nuclear energy research and kept working in that direction. Energy research was 90 percent nuclear energy research. When Matthöfer launched the programme, the European ELDO-Programme had just begun. The DFVLR site in Lampoldshausen near Stuttgart participated in that. After one failed rocket launch, this programme did not really move ahead. So the decision was made to build up energy research in Stuttgart as a new priority.

That sounds pretty much like a cold start...

Not entirely. From its aeronautic activities, the DFVLR had gained expertise in fuel-cell technology and combustion processes, among other things. And the cradle of modern wind turbines was also in Stuttgart. For example, Ulrich Hütter, who worked at DLR for a number of years, had already developed a three-blade wind turbine in 1957 – a milestone in wind energy research. The team in Stuttgart and at the Lampoldshausen site got together to draw up proposals for future energy research; many ideas came from aerospace. One of these ideas was to develop a peak load power plant on the basis of a hydrogen rocket engine. After the oil crisis people were afraid of power plant outages. The hydrogen power plant was supposed to be able to generate steam within five seconds to produce 10 megawatts of power. A demonstrator was in fact built together with an energy supplier. These were the first tentative attempts to develop new energy sources.

And how did you get involved in energy research yourself?

Since 1966, I had been working on injection coolers for rocket engine test rigs, among other things, so I was involved with physical phenomena, such as heat and mass transfer. These were things that came in quite handy for developing solar power plants and solar-thermal hot water collectors. At that time, I offered to go to Stuttgart if I could have my own research group. Two associates were assigned to me. That is how it began.

What was your task?

As engineers, we all came from the hardware side. But, even then, I was interested in the burning question of how society could abandon nuclear energy and fossil resources. We were quite familiar with the risks of nuclear energy back then. From that point on, our task was to analyse energy systems, later the complete energy market. In short, we tried to answer the question of which forms of energy could supply Germany safely and in an environmentally friendly way in the future.

Today you are best known as the father of major energy studies. That was probably new territory at the time.

It was in fact new territory. The AGF launched a major study at the end of the 1970s, entitled 'Development of Secondary Energy Systems in the Federal Republic of Germany.' In this study, the issue was first of all the transport of energy, gas, electricity and especially district heating. It was a big issue. The idea was to extract heat from nuclear power plants and deliver it to consumers over dozens of kilometres. The Research Centre at Jülich, RWTH Aachen University, and Ruhrgas AG were some of the institutions that participated in the study. It provided us with the first comprehensive overview of the German energy system. The study was published in 1979. It was 2000 pages long and was our 'journeyman'. Politically, we did not cause any big waves. But it finally started a debate about energy production among experts.

What was this debate like?

Nuclear power advocates still had influence. The Federal Government established a study commission that was supposed to investigate the need for nuclear energy. Its conclusion was that the continuously increasing demand for electricity could only be met by massively expanding nuclear energy production. The commission calculated that Germany would need 200 reactors by the year 2000. On the other hand, there were, among others, our DLR group, the Fraunhofer ISI with the group led by Eberhard Jochem, and the founding fathers of the Ökoinstitut. At that time, we demanded that energy efficiency play a major role, and we developed scenarios accordingly. Today I see this work as the precursor to the first scenarios that heralded the energy turnaround.

But that was still 30 years into the future...

... during which we learned a great deal. In 1978 Carl-Jochen Winter came to Stuttgart as the new Executive Board Member for energy research. He is a strong proponent of hydrogen as a source of energy. We intensively researched the prospects of hydrogen for a number of years – a tour d'horizon of hydrogen, so to speak. Winter expanded our group to 10 scientists. Hydrogen, geothermal energy, and solar panels were the topics that the Baden-Württemberg state government especially promoted in various projects.

You also became known for the book you published in 1990 together with Joachim Luther, who later became head of the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems (ISE).

Entitled 'Energieversorgung der Zukunft. Rationelle Energienutzung und erneuerbare Quellen' [Energy Supply of the Future: Rational Use of Energy and Renewable Sources]. We anticipated many of the ideas of the future energy turnaround. We discussed subjects like the fluctuation of solar and wind power and the idea of linking north and south to be able to transport wind energy from the coasts to the centres. The time was ripe then for these technologies. There were many more studies dealing with such issues. But with this book we established ourselves as energy experts.

As we know now, there were still a lot of reservations against renewable energies in the 1990s.

Of course. On the one hand, research was just picking up steam. At DLR, for example, we set up the 'Systems Analysis and Technology Assessment' department in 1993, and I was responsible for it. One of our main tasks was to continue to develop energy scenarios. In 1993 we conducted a study for GEO-Magazin in which we illustrated the efficiency potentials of one scenario and mapped its development up to 2005. The response was incredible. There were more than 2000 requests for the study. Since there were no PDF files at the time, the GEO office could hardly keep up. On the other hand, the 1990s were a time of intense debates. Many people doubted that renewable energies could replace fossil-nuclear energy production. Sometimes it was tough to counter. In our studies, we submitted renewable energies to all the 'instruments of torture' in systems analysis: Can that work technically? Is it worth it energetically when considering the life cycle? Are they economically feasible? At that time, a drop in prices such as the one we saw for photovoltaics was not predictable.

When did the tide turn?

For sure, one important step was the Red-Green Coalition which brought the subject of renewable energies before the Federal Environment Agency. That was a sign. In 2000 we were commissioned by the Federal Environment Agency to demonstrate in a study how the German economy could be converted to regenerative energies by the year 2050. The study was then published in 2002 with the title 'Langfristszenarien für eine nachhaltige Energienutzung in Deutschland' [Long Term Scenarios for Sustainable Energy Use in Germany]. Jürgen Trittin, the Federal Minister for the Environment, publicised our scientific findings in several press conferences and made it part of the energy concept of the Federal Government at that time. Basically, the study was a formula for the energy turnaround and for phasing out nuclear energy. But the government back-tracked on this after the government change in 2005. After Fukushima, however, the CDU, as we know, got back on the original track.

To what extent was it important for you to be able to conduct research at DLR?

The decisive thing was for our study groups to be surrounded by experts that were familiar with the hardware – engineers and technicians. If you want to assess the potential of a new technology, you need specialists who know the technology. DLR had them. I recall many tough but constructive discussions, for example about the potential of hydrogen, fuel cells and solar power plants. Without these, we would not have been able to generate the scenarios. But ultimately, we were all surprised by the incredibly rapid pace at which renewable energies and the markets developed. In the 1970s we would not have even dreamt it could happen.