Brochure: Mission InSight – View into the Interior of Mars (2018)

Mission InSight – View into the Interior of Mars

Mars is a seismically active planet – quakes occur several times a day. Although they are not particularly strong, they are easily measurable during the quiet evening hours. This is one of many results of the evaluation of measurement data from the NASA InSight lander, which has been operating as a geophysical observatory on the surface of Mars since 2019. A series of six papers have now been published in the scientific journals Nature Geoscience and Nature Communications. Eight scientists from the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) have made contributions to these. The papers describe the weather and atmospheric dynamics at the landing site, its geological environment, the structure of the Martian crust and the nature and properties of the planetary surface.

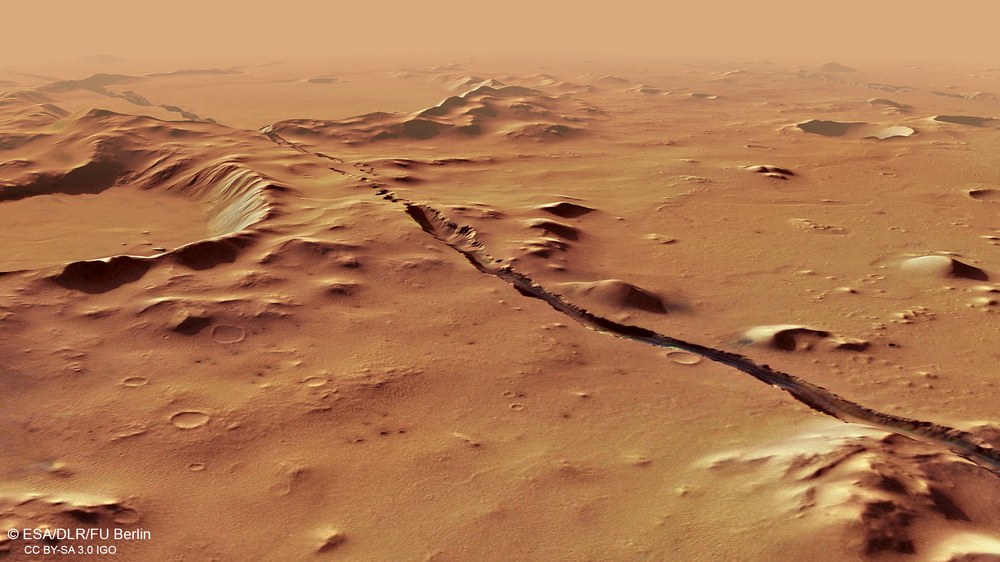

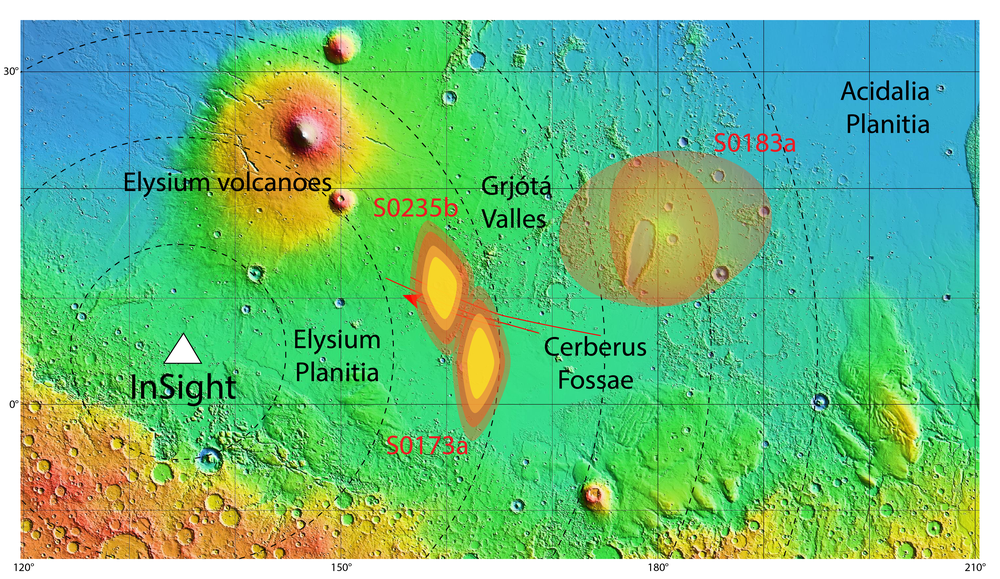

The Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument – a seismometer developed by an international consortium under the leadership of the French space agency CNES – recorded a total of 174 seismic events between February and September 2019. Twenty of these marsquakes had a magnitude of between three and four. Quakes of this intensity correspond to weak seismic activity of the kind that occurs repeatedly on Earth in the middle of continental plates, for example in Germany on the southern edge of the Swabian Jura hills. Although only one measurement station is available, models of wave propagation in the Martian soil have been used to determine the probable source of two of these quakes. It is located in the Cerberus Fossae region, a young volcanic area approximately 1700 kilometres east of the landing site.

"Due to the higher gravity, SEIS could only be tested to a limited extent on Earth. We are all very excited about how sensitive it actually is," says Martin Knapmeyer, a geophysicist at the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, who is involved in SEIS data evaluation. "The seismic activity observed on Mars so far is significantly stronger than that found on the Moon – which is what we expected. How much stronger it actually is and whether there are more powerful marsquakes than those of magnitude four will become clear as the mission continues." However, even now, important and fundamentally new conclusions can be drawn about the planet's internal structure: "Similar to the Moon, the crust seems to be heavily disrupted down to a depth of several kilometres. Nevertheless, the seismic signals are more similar to Earth than to the Moon, but we do not yet understand why. For example, much of the time we cannot identify the cause of the marsquakes. Here, we are breaking new scientific ground." The mission will continue at least until the end of 2020 and will continuously provide further data. "We have not detected any meteorite impacts yet. However, it was clear early on that only expect a very small number of impacts would be expected during the mission."

This is the first time that an experiment to record marsquakes has provided such data on a larger scale and over a longer period of time. After the Moon, Mars is only the second celestial body other than Earth on which natural quakes have been recorded. It is true that instruments for performing seismic measurements were also installed on the first landers to visit Mars – the legendary Viking 1 and 2 missions – which arrived there in July 1976. However, these instruments were located on the lander platforms and only provided 'noisy' results, which were not particularly meaningful due to the presence of interfering signals, particularly those caused by the wind.

Following its launch on 5 May 2018, InSight landed on 26 November of the same year in Elysium Planum, four-and-a-half degrees north of the equator and 2613 metres below the reference level on Mars. The InSight team named the landing site ‘Homestead hollow’. More precisely, the landing site is located in an old, shallow crater that is approximately 25 metres across. The crater is heavily eroded and filled with sand and dust. The more distant surroundings of InSight are not very interesting geologically, but that was exactly one of the most important criteria for the selection of the landing site. It needed to be flat and level – and have as few rocks and stones as possible. The entire region consists of lava flows that solidified two-and-a-half billion years ago and were subsequently broken down by meteorite impacts and weathering into what is referred to as 'regolith'. It is thought that there are no large boulders down to a depth of at least three metres.

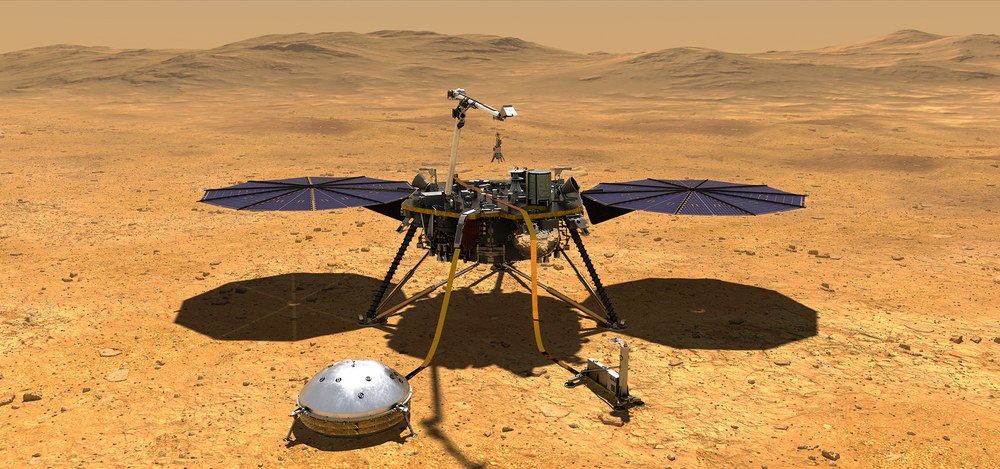

InSight, a NASA Discovery-class mission, is the first purely geophysical observatory on another celestial body in the Solar System. Its primary objective is to study the composition and structure of Mars, its thermal evolution and current internal state, and current seismic activity. Forces and energies inside a planetary body 'control', to some extent, geological processes – the results of which are visible on the surface – such as volcanism and tectonic fractures in the rigid crust, over billions of years.

With SEIS and the DLR Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) geothermal sensor system, together with a collection of supporting instruments (the Auxiliary Payload Sensor Suite (APSS) – consisting of a barometer, an anemometer, a magnetometer, and two cameras), the HP3 radiometer and the Rotation and Interior Structure Experiment (RISE), InSight takes the 'pulse' of the Red Planet, measuring irregularities in its daily rotation and recording atmospheric parameters and weather at the landing site. One surprising result has been the local detection of a magnetic field that is 10 times stronger than predicted using the results of observations from Mars' orbit. This magnetic field is generated by magnetised minerals in the rock. The magnetisation ultimately came from a planet-wide magnetic field from Mars' early history.

Before the turn of the year 2018/2019, the SEIS experiment was set down on the surface of Mars and, protected from wind and weather by its characteristic dome (resembling a 'Cheese Bell') and perfectly horizontally aligned by a levelling system developed at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Göttingen, started routine measurement operations in February 2019. The experiment is so sensitive that almost any small change at the landing site is recorded as a signal: Movements of the robot arm, gusts of wind, thermal 'stress' in the lander caused by temperature differences, or of course the vibrations of the hammering Mars Mole right beside it. For this reason, the daily weather patterns, in particular the activity of the wind and the extreme fluctuations in temperature in the day and night rhythm, as well as the vibrations caused by the hammering mechanism of the DLR experiment HP3 were analysed.

"We are dealing with much greater temperature differences at the landing site than those that occur on Earth," explains Nils Müller from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, who has analysed thermal radiation from the surface using the HP3 radiometer experiment. "At midday, the Sun heats the fine sand on the surface to above zero degrees Celsius on most days, while the thin atmosphere remains 10 to 20 degrees Celsius colder. At night, however, temperature drops to minus 90 degrees Celsius or even lower."

During the day, the increase in temperature always results in a very characteristic weather pattern, with winds first freshening and then easing in the afternoon. The scientists have even identified traces of small tornadoes or 'dust devils', frequent phenomena in the Martian weather pattern, on the ground after their course was recorded from orbit by NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) orbiter. These dust devils can even raise the Martian soil a little, which is registered by the seismometer. This allows conclusions to be drawn about the properties of the upper layer of the surface material. At night, the weather calms down noticeably, so the best time window for recording distant marsquakes is in the first half of the night, because almost no atmosphere-induced noise interferes with the experiment.

Measurements and observations performed by DLR's HP3 experiment have also been incorporated into the scientific inventory, including the radiometer data and the soil properties derived from the course of the experiment to date, with the hammering of the Mars Mole serving, among other things, as a seismic source for analysing the upper layer of the soil. However, it has not yet been possible to use the self-hammering thermal probe to penetrate deeper than 38 centimetres into the Martian soil there, with its unusual properties, even for Mars. In autumn 2019, the experiment seemed to be well on its way – the 'Mole' was given lateral support by the scoop on the robotic arm, which provided the friction necessary for driving into the subsurface. "After the Mole was almost completely in the Martian soil, it backed out again a small distance. Subsequently, with repeated lateral pressure from the robotic arm, it has moved a little deeper into the ground again with a recent slight backward movement," explains the Principal Investigator of the HP3 experiment – Tilman Spohn from the DLR Institute of Planetary Research. "In the coming weeks we want to help more effectively by applying pressure from above with the scoop on the robotic arm." For months, DLR researchers and numerous technicians and engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) have been working meticulously with the Mole on Mars and with simulations, models and tests on Earth to find a solution. In his P.I. blog, Tilman Spohn explains the current situation and the possibilities for moving deeper into the soil with the Mars Mole.

The InSight mission is being carried out by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, on behalf of the agency's Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA's Discovery Program. DLR is contributing the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) experiment to the mission. The scientific leadership lies with the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, which was also in charge of developing and implementing the experiment in collaboration with the DLR Institutes of Space Systems, Optical Sensor Systems, Space Operations and Astronaut Training, Composite Structures and Adaptive Systems, and System Dynamics and Control, as well as the Institute of Robotics and Mechatronics. Participating industrial partners are Astronika and the CBK Space Research Centre, Magson GmbH and Sonaca SA, the Leibniz Institute of Photonic Technology (IPHT) as well as Astro- und Feinwerktechnik Adlershof GmbH. Scientific partners are the ÖAW Space Research Institute at the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the University of Kaiserslautern. The DLR Microgravity User Support Center (MUSC) in Cologne is responsible for HP3 operations. In addition, the DLR Space Administration, with funding from the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, supported a contribution by the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research to the French main instrument SEIS (Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure).

Detailed information on the InSight mission and the HP3 experiment is available on DLR's dedicated mission site, with extensive background articles. Information can also be found in the animation and brochure about the mission or via the hashtag #MarsMaulwurf on the DLR Twitter channel. Tilman Spohn, the Principal Investigator for the HP3 experiment, is also providing updates in the DLR Blog portal about the activities of the Mars Mole.