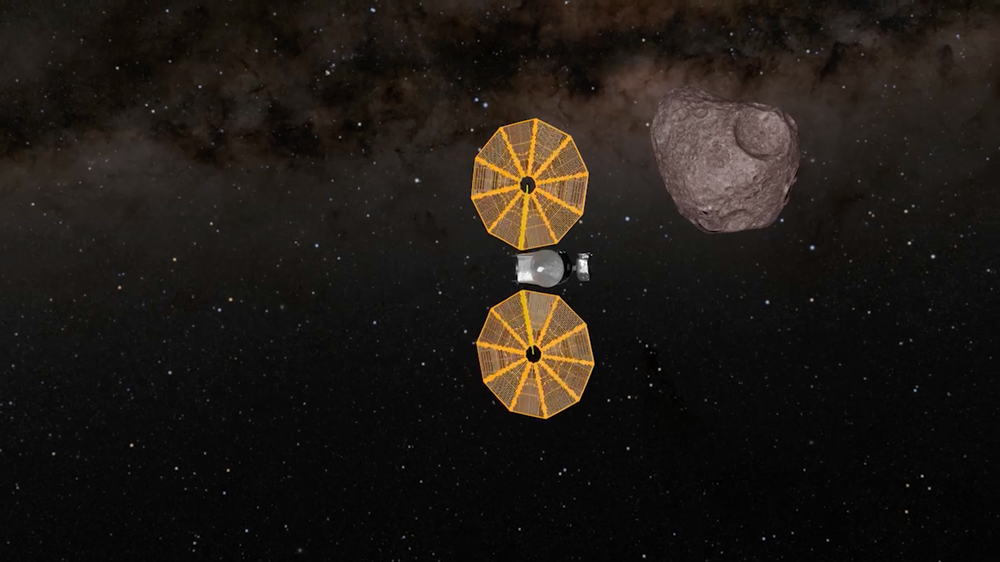

New, first destination for the Lucy spacecraft – a visit to Dinkinesh, 'you are marvellous'

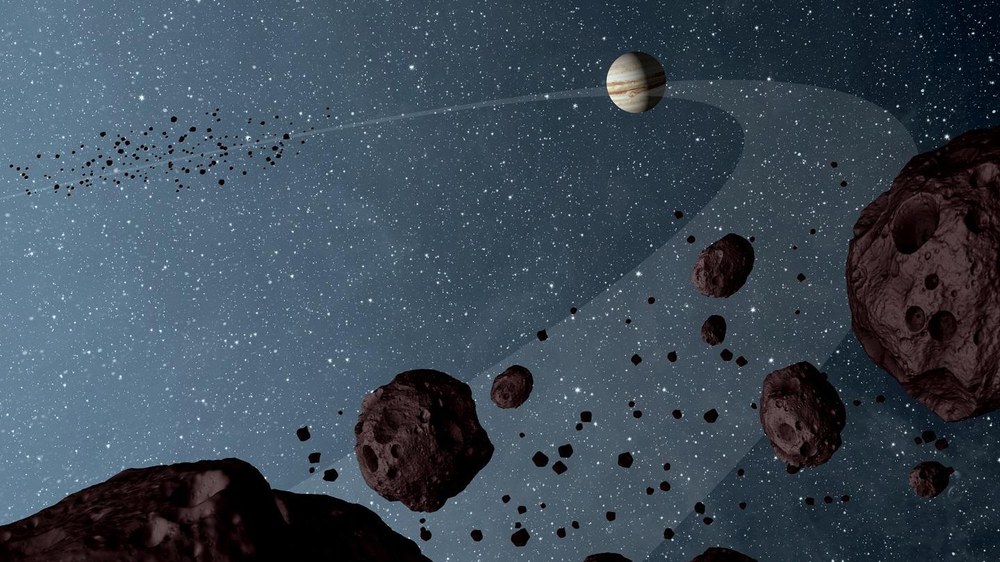

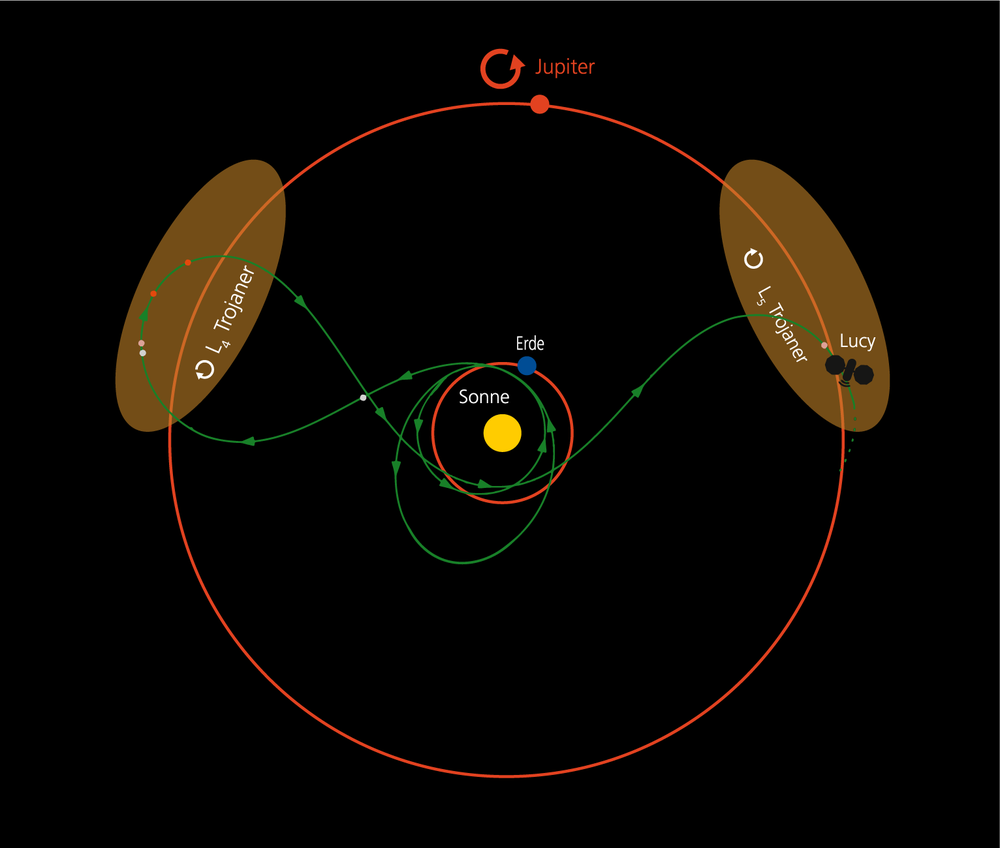

NASA/GSFC

Almost exactly two years ago, NASA launched the Lucy mission with a new and unusual task in the exploration of the Solar System. From 2027 to 2033, the spacecraft will investigate a number of asteroids referred to as 'Trojans', which lie 60 degrees of arc ahead of and behind the planet Jupiter on its orbit around the Sun. This time, Lucy is not, as is so often the case, an abbreviation for a string of technical terms, but the naming of the mission after a fossil link between upright walking apes and the first humans. Figuratively speaking, this mission, as so often with the study of asteroids, is about better understanding the earliest days of the Solar System. How did molecular chains, then dust and gas, and, soon after, the first planetesimals finally form the planets of the Solar System more than four and a half billion years ago? For now, however, Lucy is being steered past a 'conventional' asteroid in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Lucy, 'the original', is part of a hominid skeleton, the early human so important for evolutionary research, which was found in Ethiopia in 1974. Its discoverer, Donald Johanson, and his excavation team named the find 'Lucy' in reference to the popular Beatles song Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds (which was playing on a cassette recorder at the spontaneous discovery party in the evening), because the find is the skeleton of a young woman. In the Afar Plain, the place of discovery, Amharic is spoken, and in this language Australopithecus afarensis was given the name 'Dinkinesh', which means 'you are marvellous'. Dinkinesh is now also the name of a 700-metre asteroid discovered in 1999, not by chance of course. It will be the first 'marvellous' flyby target of the Lucy spacecraft on 1 November 2023.

NASA/GSFC

The Lucy team at DLR is looking forward to the Dinkinesh flyby

Dinkinesh is the smallest object in the main asteroid belt to be observed at close range by a spacecraft. The flyby distance will be 425 kilometres, giving the experiments on board Lucy excellent observation opportunities. For example, craters only 35 metres in diameter will be visible. During the flyby, the spacecraft will be able to observe 50 percent of the asteroid's surface, which corresponds to an area of approximately 0.75 square kilometres. The DLR Institute of Planetary Research in Berlin is heavily involved in the mission from a scientific point of view. Stefano Mottola is Co-Investigator in the mission's science.

NASA/GSFC

In addition to its general duties in the science team, the Institute is responsible for a wide range of tasks, such as the international coordination and implementation of ground-based astronomical observations of the target asteroids with telescopes. The light curves obtained in this way provide initial clues about the properties of these asteroids. The astronomical data can also be used to create initial models of the shape and rotation rates of the small bodies and to refine plans for flybys of these asteroids. Once the measurement data is back on Earth after the flybys, Stefano Mottola and his team will create 3D models of the bodies and derive further data products for scientific evaluation from the image data acquired by the mission. This will also be done for Dinkinesh, as well as for (52246) Donaldjohanson, which is the next flyby target in the asteroid belt.

NASA/Bill Ingalls

Stefano Mottola is particularly interested in the evaluation of photometric light curves of the target objects, that is, the measurement of the reflectance properties of the surface material as a function of the wavelength and the angle of incidence and reflection in both visible light and the near infrared.

New target and revised, but scarcely changed course

(152830) Dinkinesh, as it is officially known to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), was discovered in 1999 using a telescope in the US state of New Mexico in the course of the Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR) project. This is named after the Lincoln Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston, which was set up to search for near-Earth asteroids. Later, the asteroid, provisionally named 1999 VD57, was also observed using the Very Large Telescope operated by the European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO) in Chile, and the calculation of its orbit around the Sun was refined.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

Martin Lockheed

The small asteroid became an additional first mission target for Lucy, instead of the asteroid (52246) Donaldjohanson, through calculations performed by Raphael Marschall at the Côte d'Azur Observatory in Nice, who is a member of the Lucy team. After looking at half a million asteroid orbits, Marschall realised that 1999 VD57 could be reached by Lucy with very minor orbital changes. On 25 January 2023, the Lucy team selected 1999 VD57 as an additional flyby target for the mission. On 6 February 2023 the IAU gave the asteroid a name associated with 'Lucy' at the suggestion of the Lucy team.

With a distance from the Sun varying between 291 and 364 million kilometres, Dinkinesh moves in a highly elliptical orbit inclined at 2.09 degrees to the ecliptic (the orbital plane of Earth around the Sun). It takes Dinkinesh three and a quarter years to complete one orbit around the Sun, and its rotation period is just under 53 hours. With an albedo of 40 percent, Dinkinesh is a fairly bright asteroid, belonging to the class of silicate-rich S-types (the second most common group of asteroids at 17 percent) or the rarer V-types (named after the second largest asteroid, Vesta, and similar to the S-types).

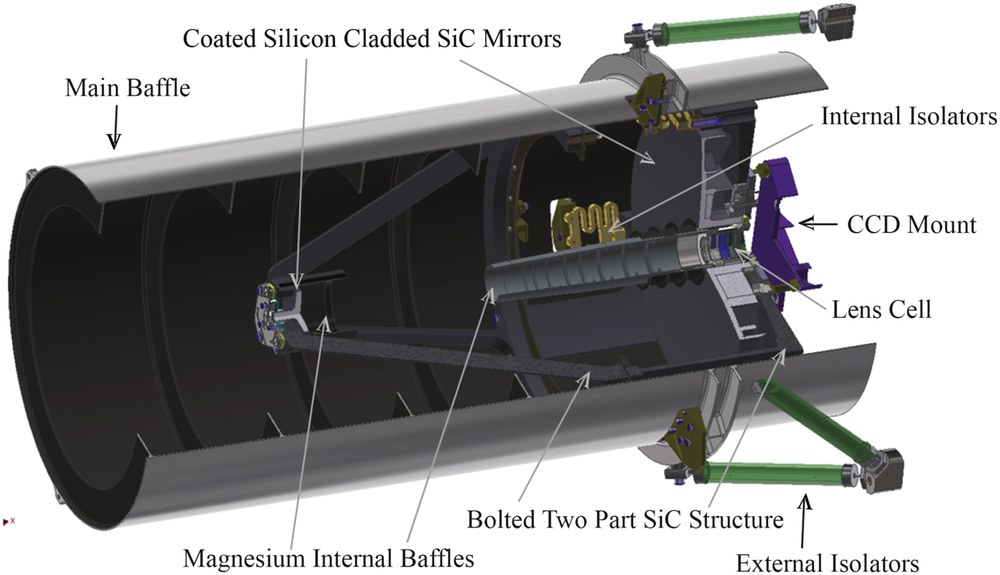

SWRI/DLR

Higher precision when targeting thanks to new technology

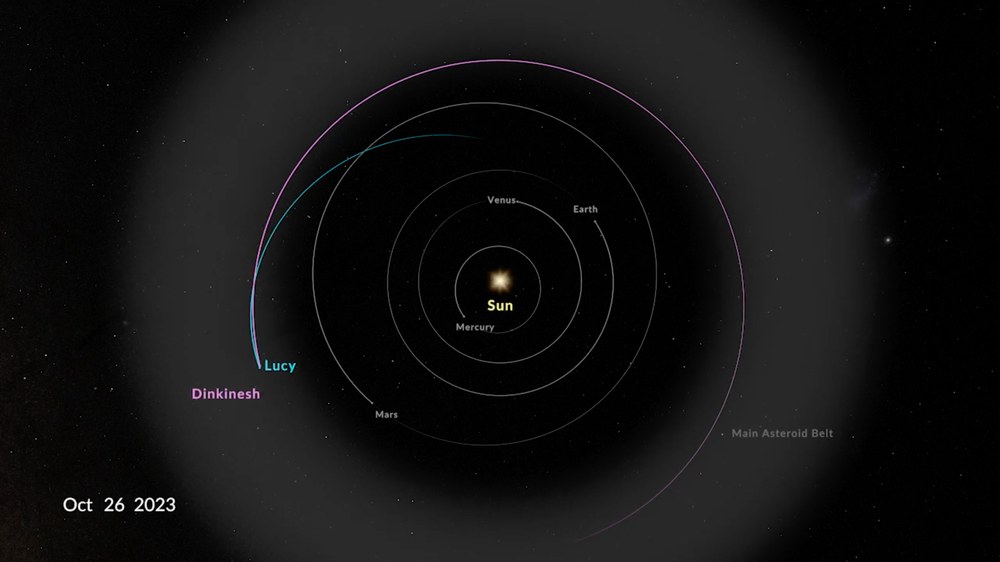

Lucy first imaged its new target on 3 September 2023, by which time the spacecraft had already travelled almost 60 million kilometres. These images were mainly for improved navigation during the close flyby. To get close to Dinkinesh, after analysing the data and programming the spacecraft, a small corrective manoeuvre was performed on 29 September, changing the speed of the spacecraft by just six centimetres per second. This will bring Lucy within the planned 425 kilometres of Dinkinesh. On 16 October, Lucy was only 4.7 million kilometres away from Dinkinesh. Since the asteroid is also moving around the Sun, Lucy will have to 'chase' Dinkinesh for another 25 million kilometres at a slightly higher speed, so to speak, before the actual flyby takes place. At the end of October, if necessary, another fine-tuning for the close flyby could have taken place. The fact that the spacecraft and its target were obscured by the Sun for a few days from 6 October onwards and radio communication with Lucy was not possible during this time made planning a little more difficult.

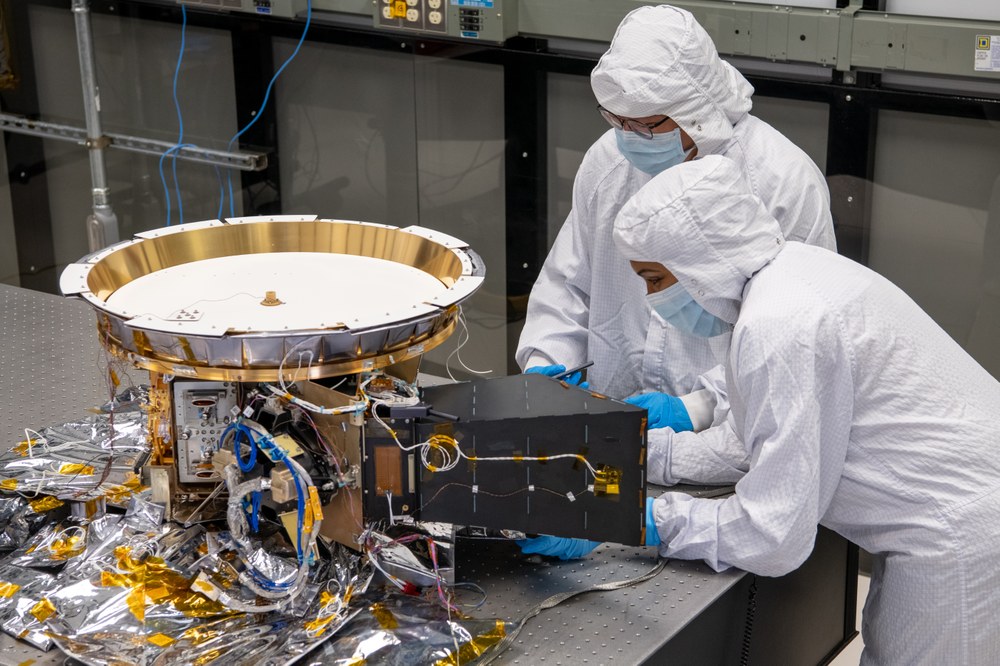

Johns Hopkins/APL

There were good scientific reasons for adding a flyby to Lucy's grand, complex tour of the outer Solar System. For NASA, however, the technical aspects provided the more important arguments. From a research perspective, the team hopes to use Dinkinesh to study an interesting link between the larger objects of the main asteroid belt, which were also visited by previous missions, and the near-Earth asteroids. The main task of the flyby, however, is an early test of the instruments and the procedures for the experiments, as well as a first dress rehearsal of the Terminal Tracking System (TTS). This is because the flyby and illumination geometry of Dinkinesh will be similar to that of flybys later in the mission.

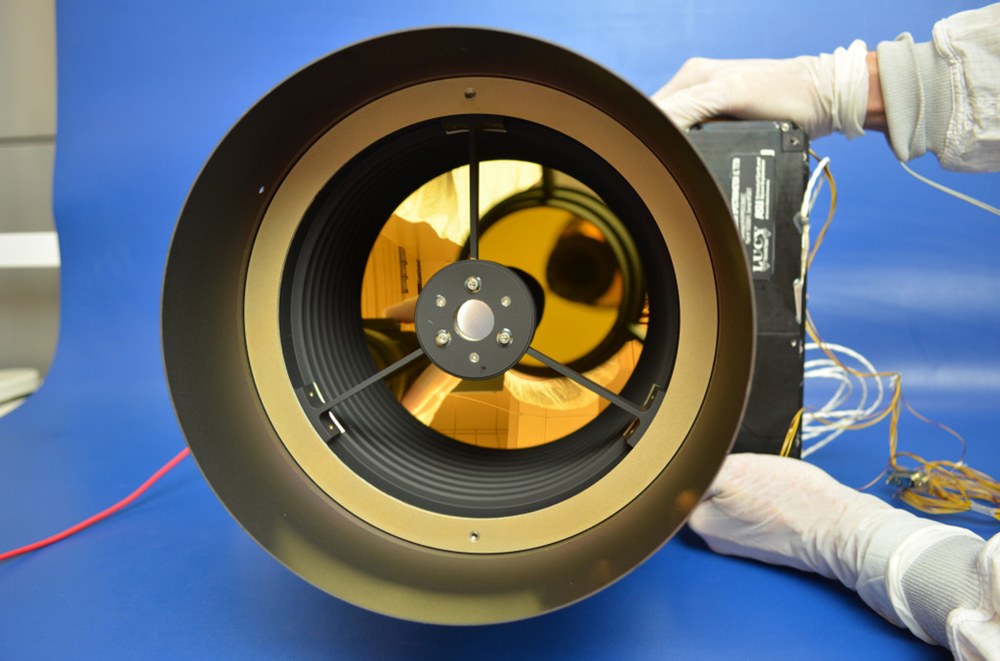

NASA/Goddard/SwRI/Johns Hopkins APL

Later in the mission, the TTS should make it possible to improve the automated targeting of the much more distant asteroids in Jupiter’s orbit by using the image data during the approach. This 'improved targeting', which has not previously been technically possible, should lead to a better image and data yield because it is more 'targeted'. The exact position of small bodies such as asteroids cannot be accurately determined with telescopes from Earth for close fly-bys, and real-time correction of the orbit is of course impossible due to the long transit times of the radio signals. In previous missions, the instruments were therefore programmed to simply cover a large area in the hope that the target would then be well captured in at least some of the images. However, aiming 'into the blue' (or, of course, 'into the black' in space) led to many unnecessary images and thus to the loss of valuable data storage capacity. A successful test of the TTS would be a huge step forward for further planning during the course of the mission and for future missions.

After Dinkinesh, Lucy will pass yet another target in the main asteroid belt on 20 April 2025 – the four-kilometre asteroid (52246) Donaldjohanson, named after Lucy's discoverer, Donald Johanson, who celebrated his 80th birthday on 28 June 2023 – and, as can easily be made sense of from what has been explained above, that was no accident either …

More information:

- NASA video about the Dinkinesh flyby on 1 November 2023

- DLR Press Release 2021 on the start of the Lucy mission

- NASA Lucy mission

- SWRI Lucy mission

NASA/SWRI

NASA/ASU

Tags: