The SANS-CM bed rest study: Lying down for 30 days for space research

What happens to humans in microgravity conditions? How do space conditions affect the human body? How can we prevent adverse effects on long-term spaceflight? Scientists on Earth are also asking themselves these kinds of questions. And they're coming up with answers, despite the occurrence of gravity. The researchers can outsmart it, as the ongoing bed rest study at :envihab, our aerospace medicine research facility, demonstrates. Here, eight men and four women lie in bed for 30 days straight. The head end of each bed is tilted six degrees downwards and there is no pillow. In these conditions, body fluids are distributed as they would be in microgravity, flowing from the legs towards the head. The test participants are 'astronauts on Earth'.

"This can be uncomfortable for the first three to five days," says Edwin Mulder, Project Lead for the study. "Your circulatory system, back, head, digestive system – everything has to get used to it." This is another thing that the test subjects and space travellers have in common. In the absence of gravity, more than half a litre of fluid rises into the upper half of the body. This not only leads to cold feet, a hot head and a puffy-looking face. There are far more serious side effects: the unusual distribution of body fluids changes the pressure conditions. This can result in neurological effects, for example to the vision. "That's a major issue, especially during long-term missions," says Mulder. Astronauts operate instruments, determine values and work with millimetre precision – and to do this they need great visual acuity.

The LBNP vacuum cylinder draws the blood into the lower half of the body

The body fluids have to flow back into the legs. The current SANS-CM bed rest study (Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome Countermeasures study) is intended to show how this works. Like previous studies, it is being carried out by the DLR Institute of Aerospace Medicine on behalf of the US space agency NASA.

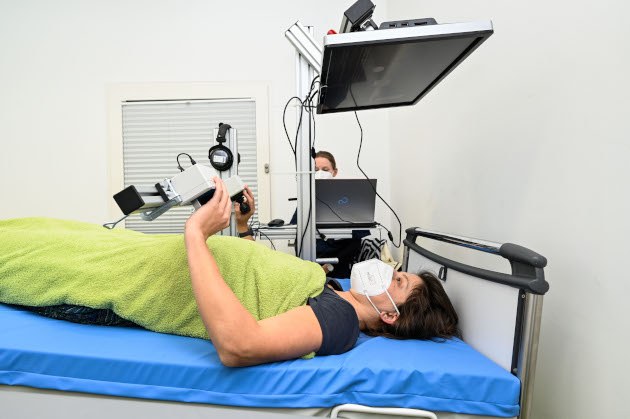

The first of four campaigns is currently underway; each will have 12 participants. It includes two weeks of preparation, 30 days in bed and two weeks of follow-up examinations and rehabilitation training – 59 days in total. During the bed phase, six people lie in a vacuum cylinder for three hours twice a day. This lower body negative pressure device (LBNP), which was built by the DLR institutes of Aerospace Medicine and Materials Physics in Space and the Systemhaus Technik in conjunction with NASA, encloses the body from the waist down. The negative pressure of 25 mmHg draws blood and fluids into the lower half of the body.

The effectiveness is assessed through tests on aspects such as cardiovascular function, balance, muscle strength and, of course, vision. The other six people from the control group sit upright in a chair for three hours twice a day. The participants in the second campaign, which will start at the end of January 2022, will work with the LBNP again. In the third and fourth campaigns, special thigh straps will be used in conjunction with cycling training.

Bed rest studies – a long-standing tradition at DLR

The first bed rest study was conducted in 1988 in preparation for the D-2 mission, which began in 1993. At that time, the Columbia space shuttle took German astronauts Ulrich Walter and Hans Schlegel into orbit for 10 days with Spacelab. Three decades later, the research is focusing on potential long-term missions, such as to the Moon or Mars. In the AGBRESA study two years ago, the participants spent 60 days in bed.

To ward off physiological changes, the training group spent 30 minutes a day in the short-arm centrifuge at the :envihab. The rapid turns while lying down allowed them to experience artificial gravity. The study showed that the effect on the body was limited after 30 minutes. "In theory, it still appears optimal to generate gravity in space. Technically, however, this cannot be implemented in a small spacecraft at this point in time," says Mulder. It would be easier to take along an LBNP with a vacuum hood and pump.

"A life-enhancing experience and adventure"

Project managers Edwin Mulder and Stefan Möstl started preparing for this study one-and-a-half years ago. After putting together a 15-person core team, they jointly planned the test methods down to the last detail. In addition to this core team, more than 100 people are assisting with the study. The selection of the test participants for the first campaign took several months. "We have to be sure that we only include people who are actually capable of undertaking the study. Spending 30 days in bed is a real physical and mental challenge," says Möstl. "That said, it's also adventure and the experience of a lifetime.“

Day-to-day life slows down. Eating, showering and going to the toilet while lying down are unfamiliar and take significantly longer, at least at first. There's a busy timetable of tests and examinations, which sometimes go on until 10 at night. Nevertheless, there's time for personal activities like reading, watching TV, talking, online games – everything that a person can do while lying down. After the bed phase, the test participants remain in the :envihab for two weeks to recover. "During this time, all of the physical changes recede," says Mulder.

The ISS astronaut next door

In November it was once again apparent how closely the two groups are connected on Earth and in space. Upon returning from the ISS, French ESA astronaut Thomas Pesquet (43) travelled directly to the :envihab, where he spent 10 days readjusting to life with gravity and continuing with his mission experiments. He underwent medical tests to investigate the consequences of his six-month stay in space on his body. These included cardiovascular examinations and eye diagnostics using eye ultrasound readings and eye tests – just like the Earth-bound astronauts in the bed rest study. Occasionally the test participants would actually cross paths with Thomas Pesquet.

Applications will soon open for the third campaign in the SANS bed rest study in early 2023. We are also looking for participants for other studies.

Tags: